In the Sweet Spot of Economics and Public Policy

The shift from natural gas importer to exporter has occurred in the U.S. over a remarkably short period of time. We’ve periodically written about this (see U.S. Natural Gas Exports Taking Off and The Global Trade in Natural Gas). Only a few years ago Cheniere Energy (LNG) was investing in facilities to import Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), anticipating that the U.S. would need to rely on foreign suppliers such as Australia and Qatar. The Shale Revolution changed all that, and the conversion of planned regasification plants to liquefaction began.

The story of how this shift occurred is only complete when the role of Cheniere’s founder Charif Souki is included. Greg Zuckerman’s wonderfully absorbing 2013 book, The Frackers paints colorful portraits of several key protagonists, and Souki is among them.

A Lebanese immigrant to the U.S., Souki’s early career was with a small U.S. investment bank where he raised money for deals in the Middle East, relying initially on his father’s contacts in the region. He was quite successful but eventually became tired of the deal making and travel. For several years he and his family lived in Aspen where he ran a restaurant. The relaxed lifestyle was a welcome change, and he enjoyed the regular visits of stars such as Jack Nicholson and Michael Douglas. However, the restaurant business wasn’t lucrative and eventually with his savings low he decided to shift directions again.

Given this background, Charif Souki was an unlikely energy pioneer. However, he applied his deal-making skills to the energy business and eventually wound up running tiny E&P company Cheniere Energy. The best part of the coverage of Souki in The Frackers describes how he convinced other investors to back him in developing LNG import facilities, only to subsequently have to raise more capital to convert them for export. It must have taken all his sales and deal-making skills to follow up one compelling vision with another, but he did.

Having brought Cheniere to the point at which it could start exports, Souki was forced out of the company by Carl Icahn. Souki’s substantial risk appetite had eventually paid off, but by then his shareholders were looking for rather less excitement. With $BNs in capital invested and contracts lasting 20+ years, the owners were looking for steady, reliable progress to realizing promised returns. Charif Souki was not that type of corporate leader.

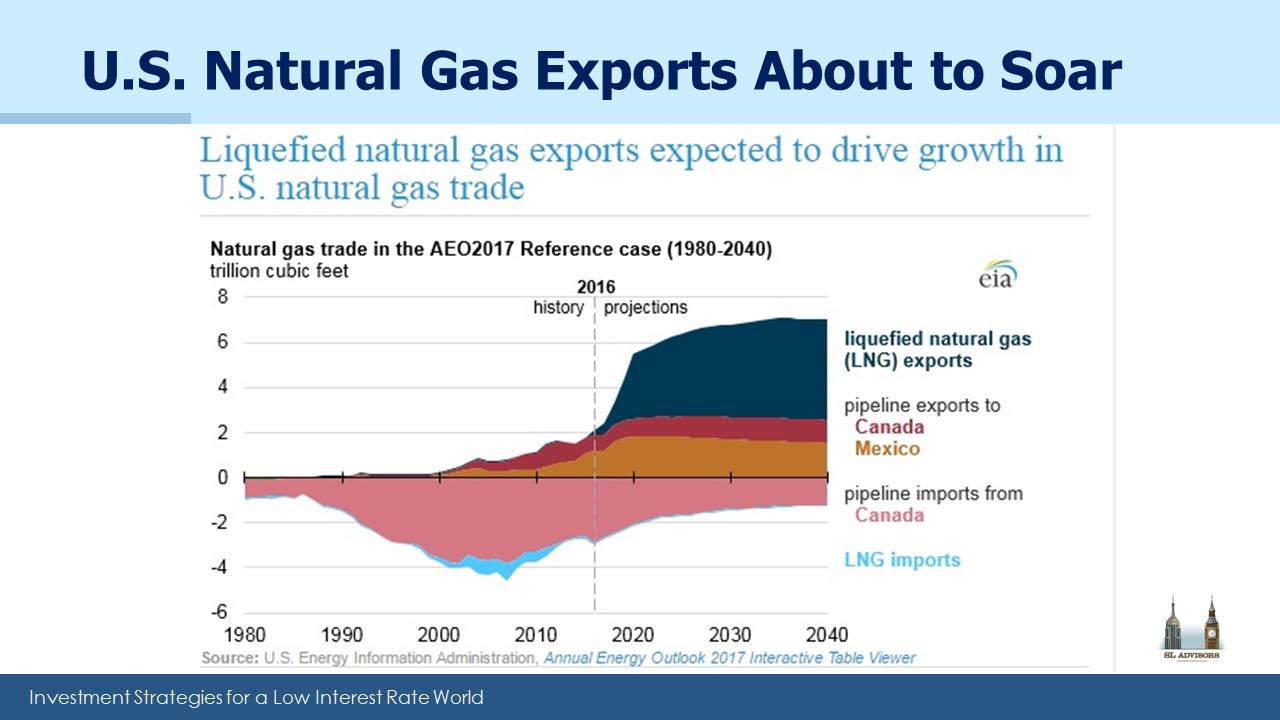

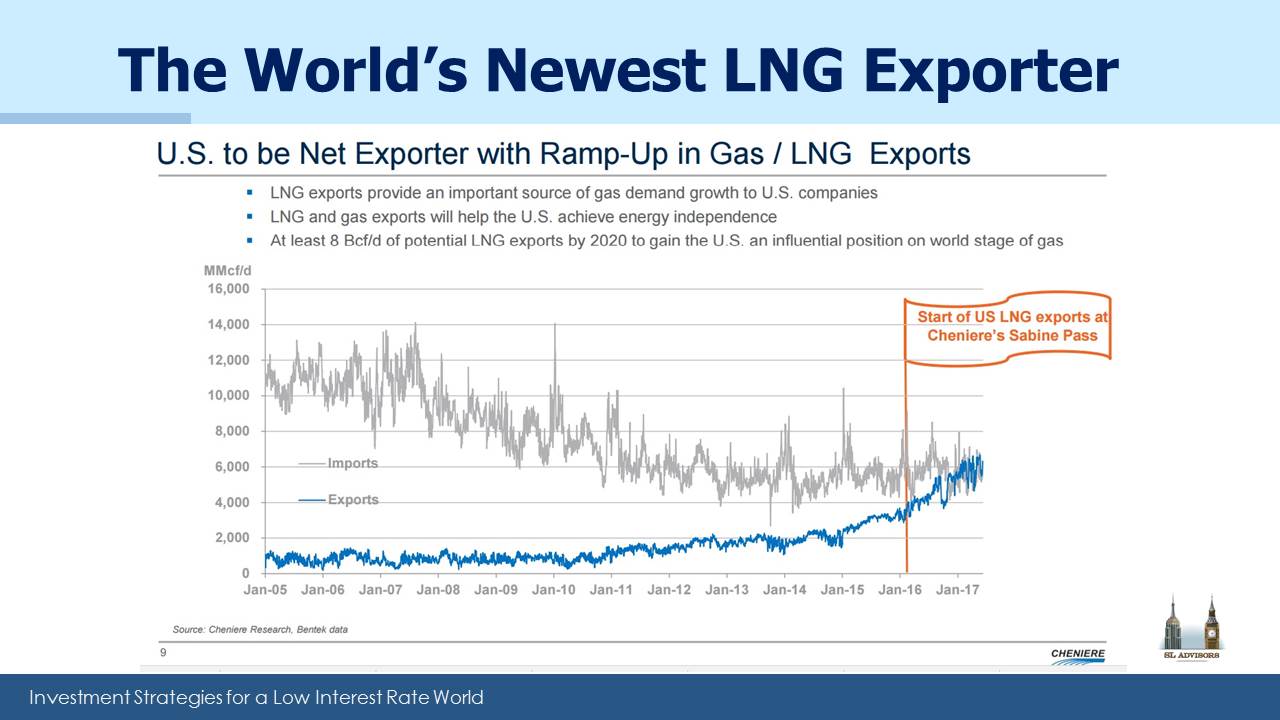

I was reminded of all this the other day when perusing company presentations from a recent Energy Information Administration (EIA) conference. This year U.S. LNG exports at times have exceeded imports, driven in no small part by Cheniere. EIA projections through 2040 show the U.S. quickly becoming a substantial exporter.

Much of the shift to U.S. exports is well known to those who follow the industry closely. What’s less appreciated is how Cheniere is aligning itself with Federal policy. The President clearly likes to promote America when he travels, and be associated with deals. On his recent trip to Poland he was pushing LNG exports. There’s no doubting the energy security benefits across Europe from diversifying their supplies of natural gas so as to be less reliant on Gazprom. Energy exports and armaments will be part of the dialogue in virtually every Presidential trip abroad, as U.S. foreign policy promotes buying energy from a stable democracy and (for NATO members) spending more on their own defense.

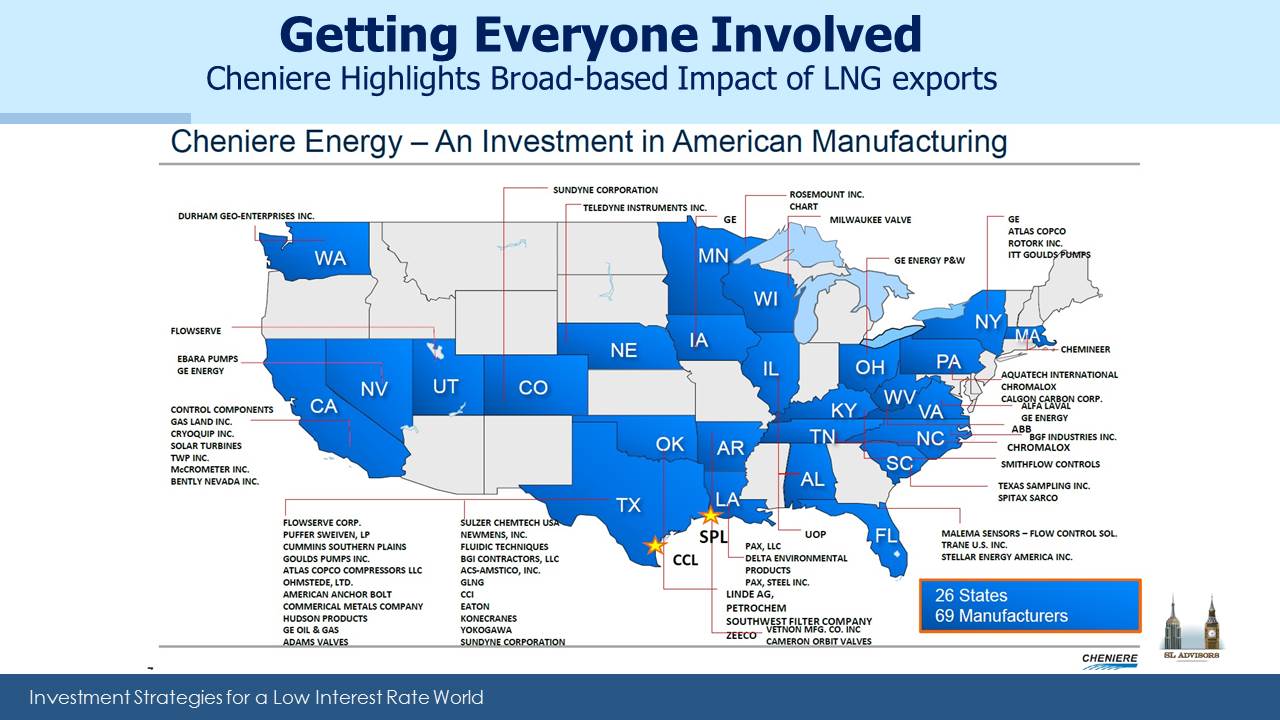

But Cheniere also understands the importance of domestic politics, as this slide shows. What could resonate more effectively with the White House than exporting domestically produced energy security around the world? Cheniere isn’t the only company to understand that they’re in the sweet spot of alignment between corporate profitability and public policy objectives.

We are invested in Cheniere Energy (LNG)