Some Energy Forecasts Are Aspirational

Long term energy forecasts are nowadays subject to a partisan test by many readers based on whether or not they project a rapid energy transition. The biggest oil and gas producers such as Exxon Mobil and Shell understand that the media interprets their published long run energy forecasts as reflecting their capex criteria. The result is a set of projections leavened with cheerleading for renewable energy, leaving the reader to separate the two.

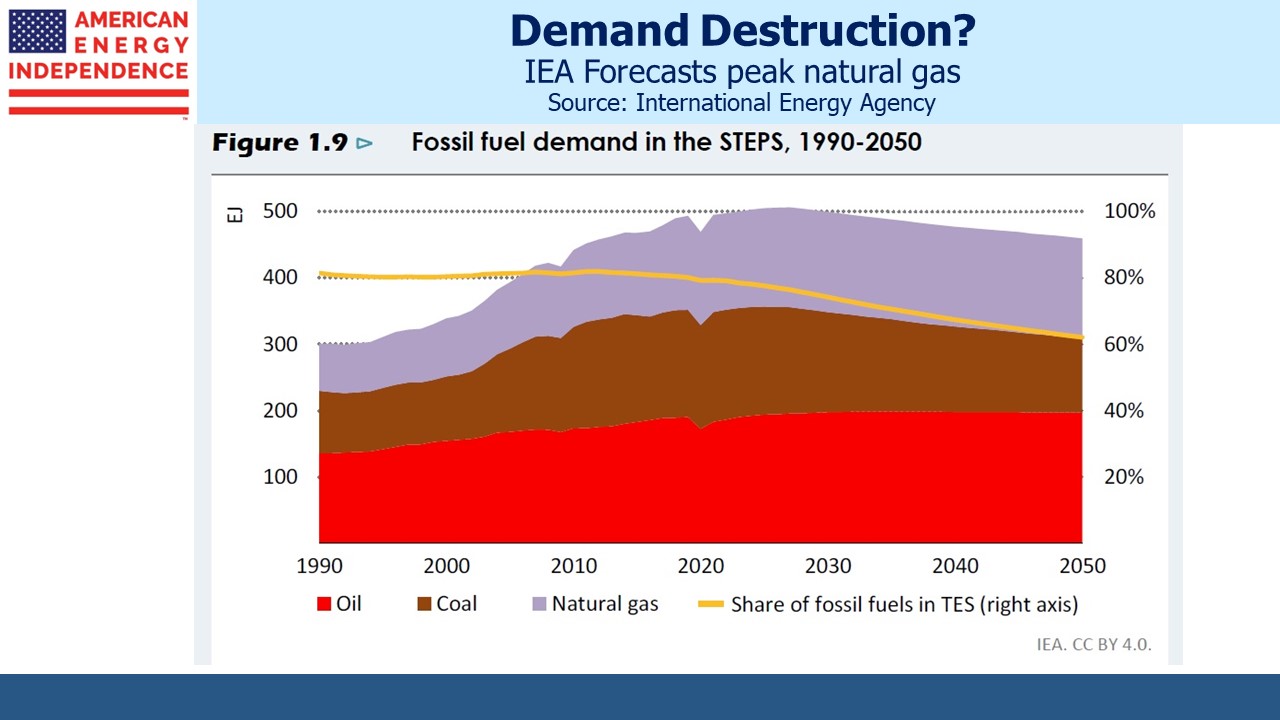

The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently published their 2022 World Energy Outlook, and for the first time it projects a peak in natural gas consumption around 2030. The shift is caused by the loss of Russian exports to Europe, which has driven prices for LNG higher. The EU will import over 1.7 Trillion Cubic Feet (TCF) of additional LNG this year. This has caused many regions, including the EU, to turn to rely more on coal, as a workable alternative to high natural gas prices. But over the next decade, the IEA has increased its forecast of solar and wind power generation too.

The IEA’s base case is the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) which assumes current policies continue. Other scenarios envisage new policies, including a set consistent with achieving zero emissions by 2050. The world isn’t even consistent with STEPS, although it remains the most plausible of the IEA’s three scenarios. Including more extreme outcomes allows the IEA to be an energy transition champion if not an unbiased forecaster.

The 2022 Outlook includes many useful facts: this year fossil fuel producers have enjoyed a $2TN jump in net income (a “windfall”) versus 2021; governments have committed over $500BN in tax breaks and energy subsidies to households, hence the trend towards taxing windfall profits in Europe. Permitting and construction of overhead electricity transmission lines can take up to 13 years, with developed countries often the slowest. 75 million people who recently gained access to electricity are likely to lose it this year.

How likely is the IEA STEPS to be right?

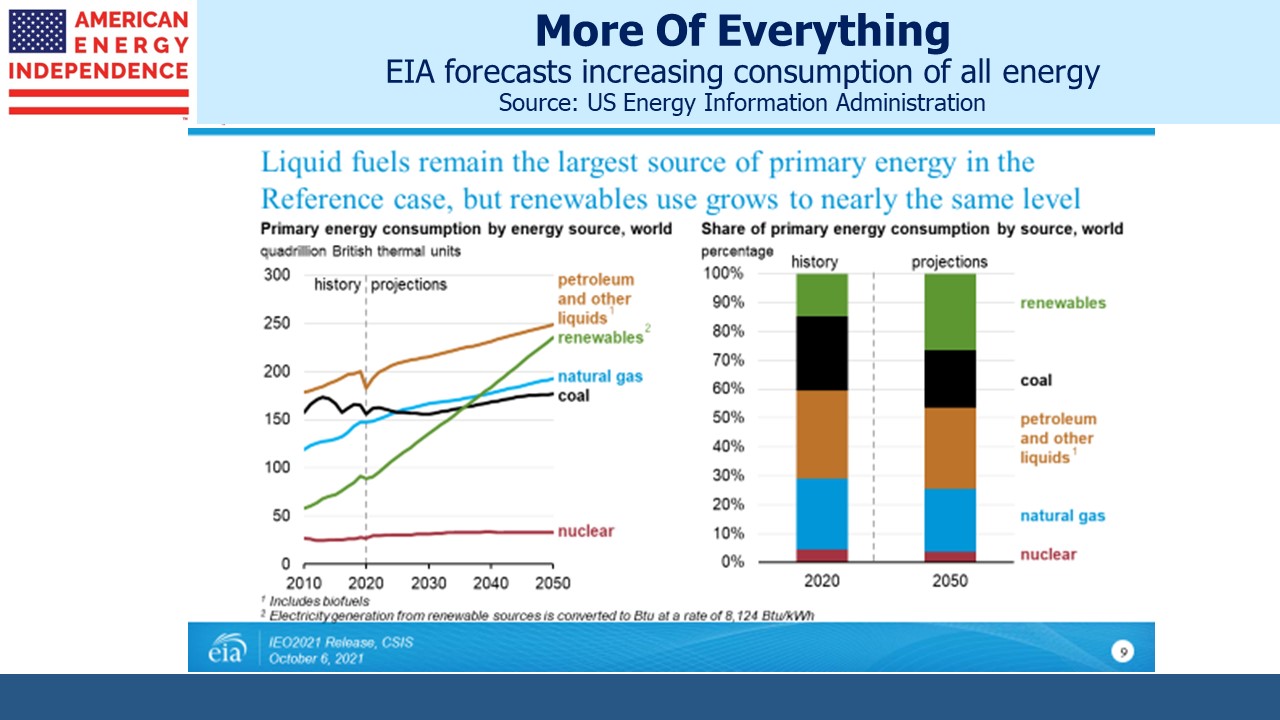

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) sees consumption of all energy sources increasing. They see renewables output more than doubling over three decades and gaining market share. Rising energy consumption to support higher living standards in the developing world is the dominant theme. The EIA sees global energy consumption rising by over 40%, a 1.2% annual rate of increase. This is slower than the 1.9% annual rate of increase the world experienced in the decade (2009-19) leading up to Covid.

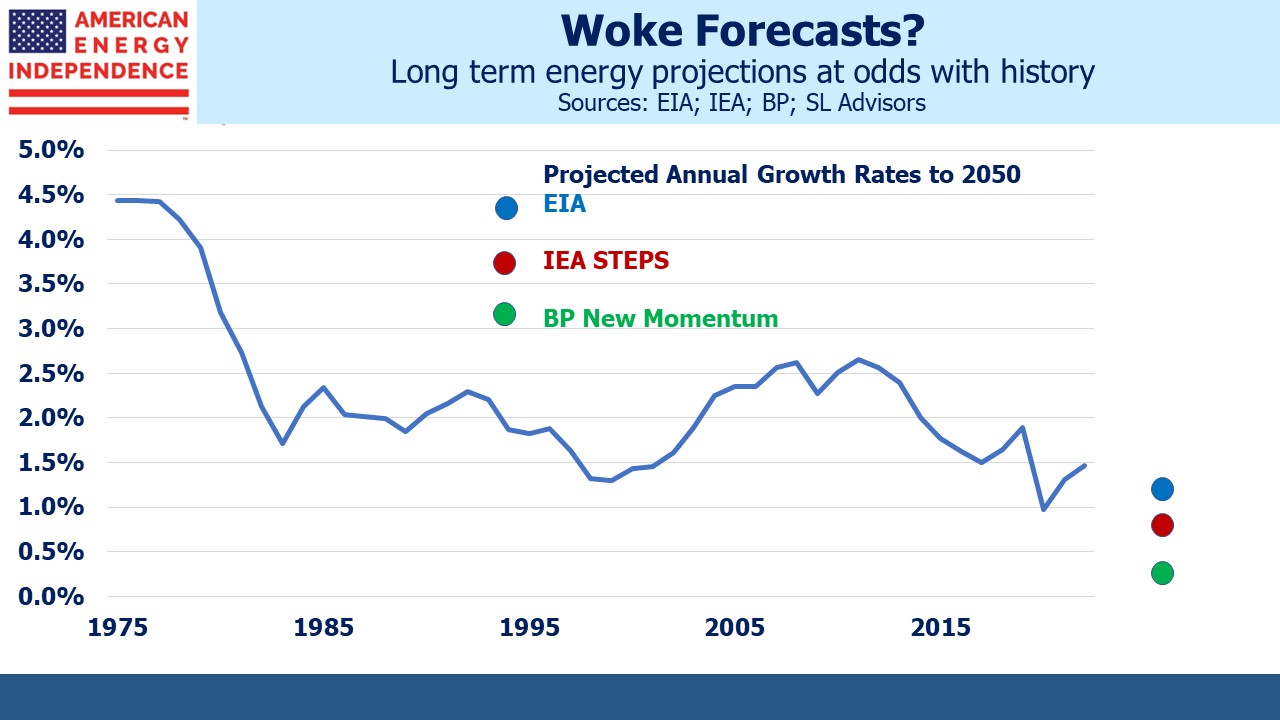

By contrast, the IEA STEPS outlook based on existing policies projects a growth rate collapsing to under 0.3% per annum. There is no basis in history to support this. It implies a much longer path to the rising living standards that are the aspiration of developing countries. Their other scenarios assume almost no growth and an actual decline.

In 2020 the world’s ten year growth rate in energy consumption dipped to 1% pa for the first time in several decades because of Covid. Last year’s 5.8% annual increase brought the ten year growth rate back up to 1.3%, and it’s likely to edge higher again after this year. Forecasts are becoming less neutral and more aspirational, a form of political correctness at large organizations that requires more skeptical reading. In BP’s projections of global energy consumption, their three scenarios are called Accelerated, Net Zero and New Momentum. Their projected annual growth rates are 0.3%, 0.1% and 0.6% respectively.

The EIA, an agency of the US Department of Energy, provides the most plausible growth rate of the three. Accepting even the most realistic forecasts of the IEA or BP suggests billions of poor people acquiescing to constrained improvement in living standards.

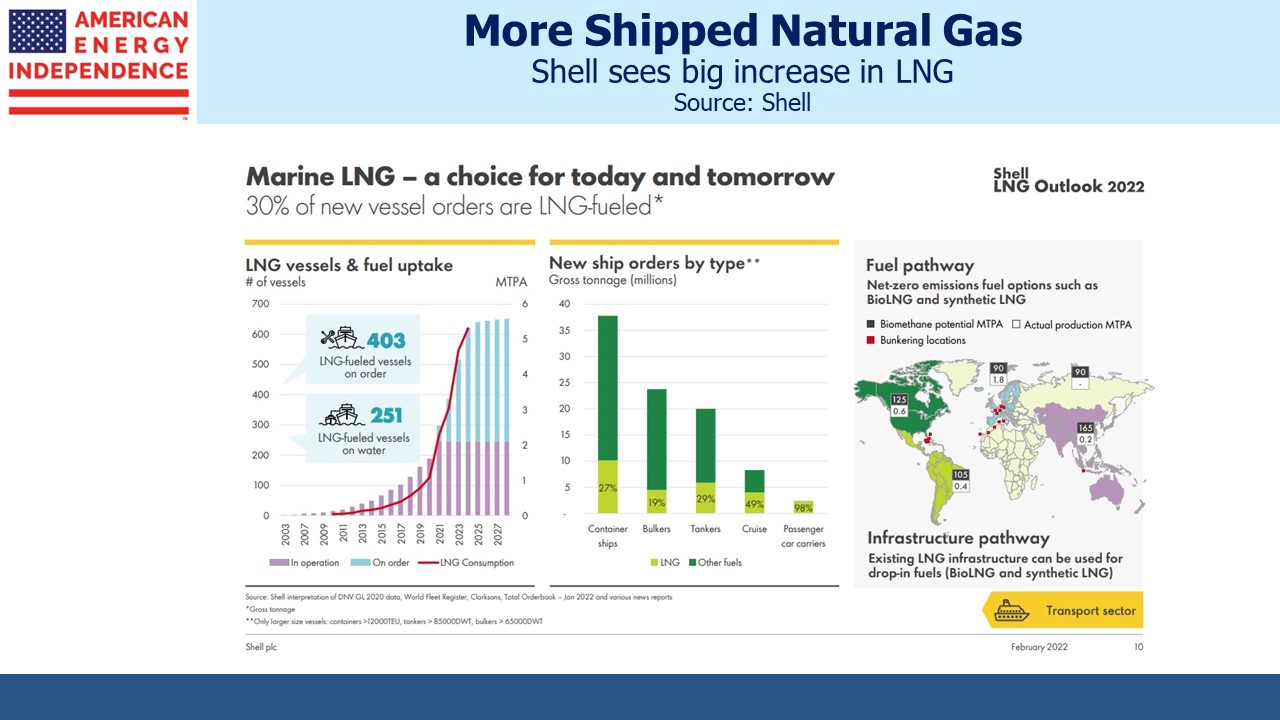

Meanwhile Shell sees a bright future for LNG.

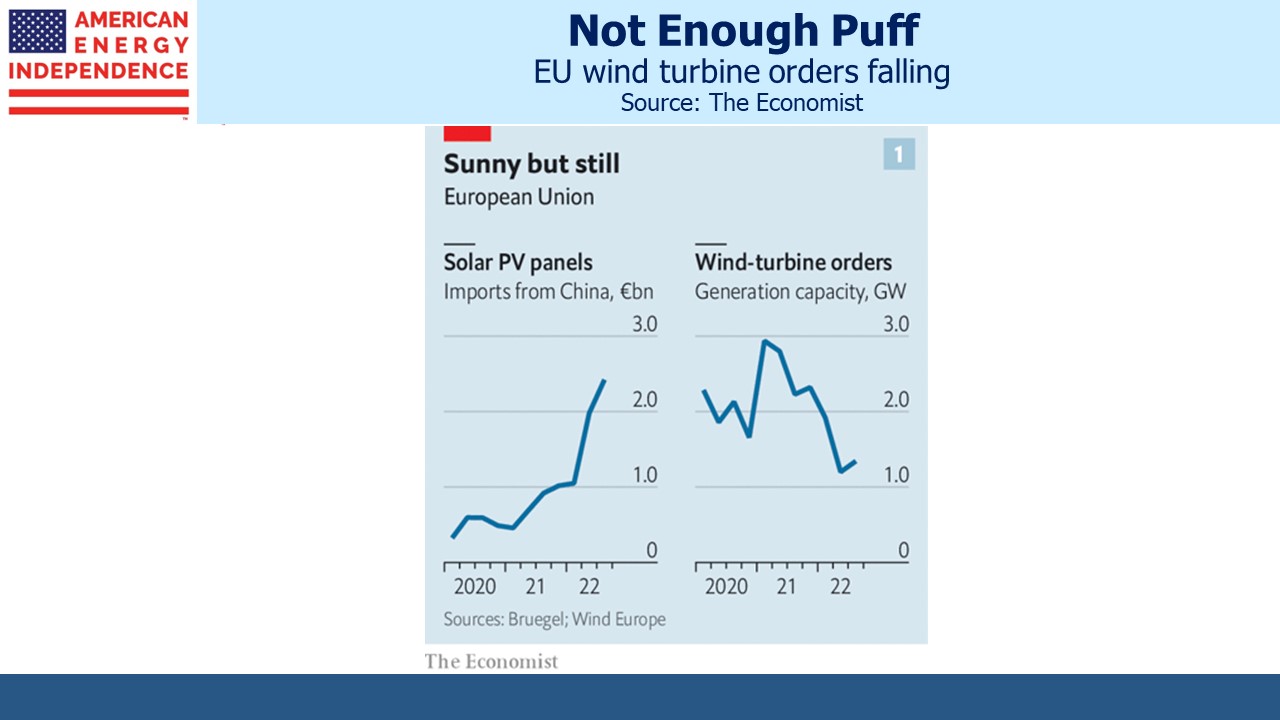

The chart showing a sharp drop in EU wind turbine orders illustrates some of the challenges facing that industry. Russia’s invasion could have been a big boost for wind (watch Why Aren’t Renewables Stocks Soaring?), but companies are struggling to make a profit.

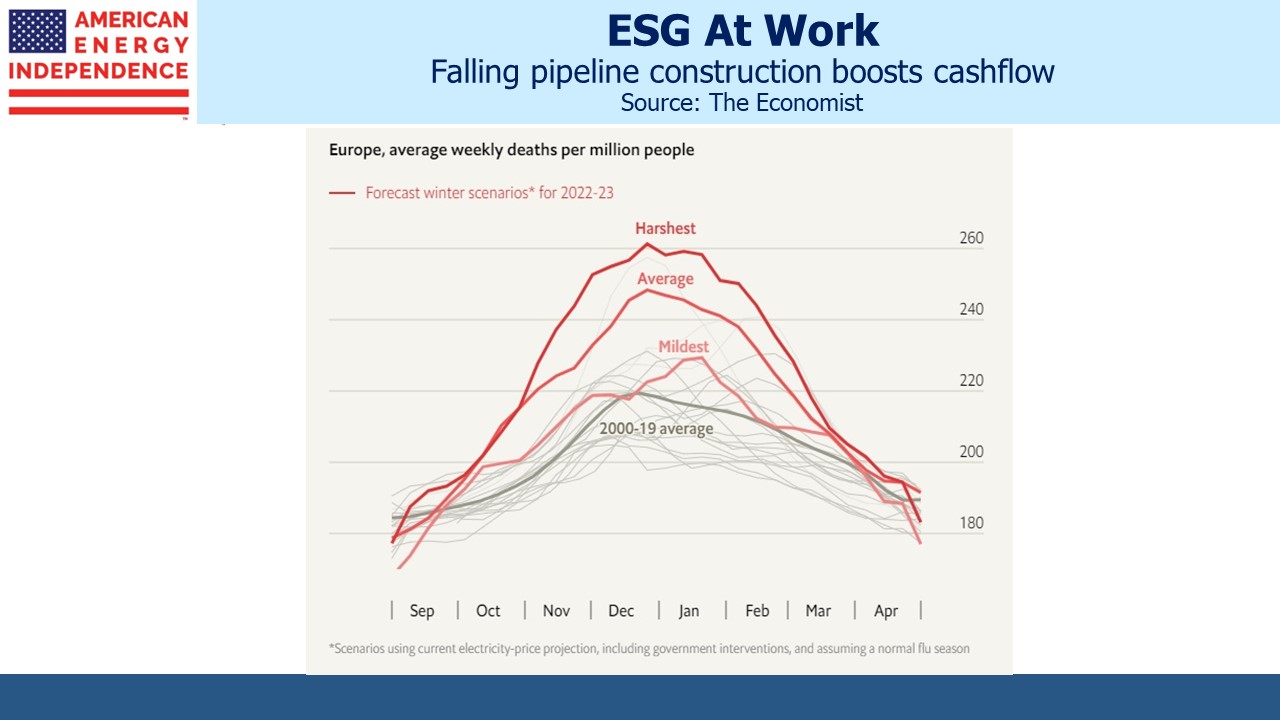

The Economist magazine is projecting an increase in deaths this coming winter, with even a mild winter causing a seasonally adjusted rise. Such are the consequences of Europe’s failing energy strategy.

Lastly, Tellurian CEO Sharif Souki is the subject of a WSJ article that examines his failure to repeat the success he enjoyed at Cheniere (see US Natural-Gas Pioneer Struggles in His Second Act). Souki is a visionary, but he’s been handsomely paid for not delivering. We highlighted this “pay for performance in advance” in a recent video (see What’s Next For Tellurian?).

Souki admitted recently that his mistake had been to retain the price risk on shipped LNG. He’s bullish on prices, but lenders don’t share his enthusiasm for the risk. Conventional LNG projects charge a liquefaction fee that largely leavers the price risk with the buyers and sellers.

Although Tellurian has been forced to adjust its business model, Souki’s expectation for continued growth in energy demand from emerging economies looks realistic to us. Forecasters such as the IEA might benefit from considering it.