Some Banks Are Having To Pay More

I’m the treasurer for our co-op in Naples, FL. I recently asked our local bank to pay a more competitive rate on our cash balance, which is well over the $250K FDIC insurance limit. Their deposit rate for business accounts was 0.5%, and maybe because Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) had just failed they quickly raised it to 3%.

This is still inadequate, and I’m not done with them yet. Banks are notoriously sluggish in raising rates when the Fed’s tightening. Depositors are slothful in demanding competitive rates. The margin below treasury bills can be thought of as the fee for banking services, although the cost in foregone interest income is more than most depositors would tolerate if asked to write a check for the amount.

Banks don’t make it easy either. Parking cash in treasury bills requires a brokerage account and the ability to easily move money back and forth. Dual sign-off for transactions is often required on business accounts. It can quickly become an administrative headache to earn a competitive rate, and banks know this.

SVB’s failure exposed imprudent risk management, but it prompted depositors to consider where their money sits and what it’s earning. Money has flowed out of regional banks, some of it to the systemically important banks (“too big to fail”). We assume deposits are fully guaranteed even though they’re legally not. There’s a de facto guarantee because allowing depositors to suffer a loss in bankruptcy might lead to another financial crisis. Size matters. A bank deemed small enough to fail is not the place to be.

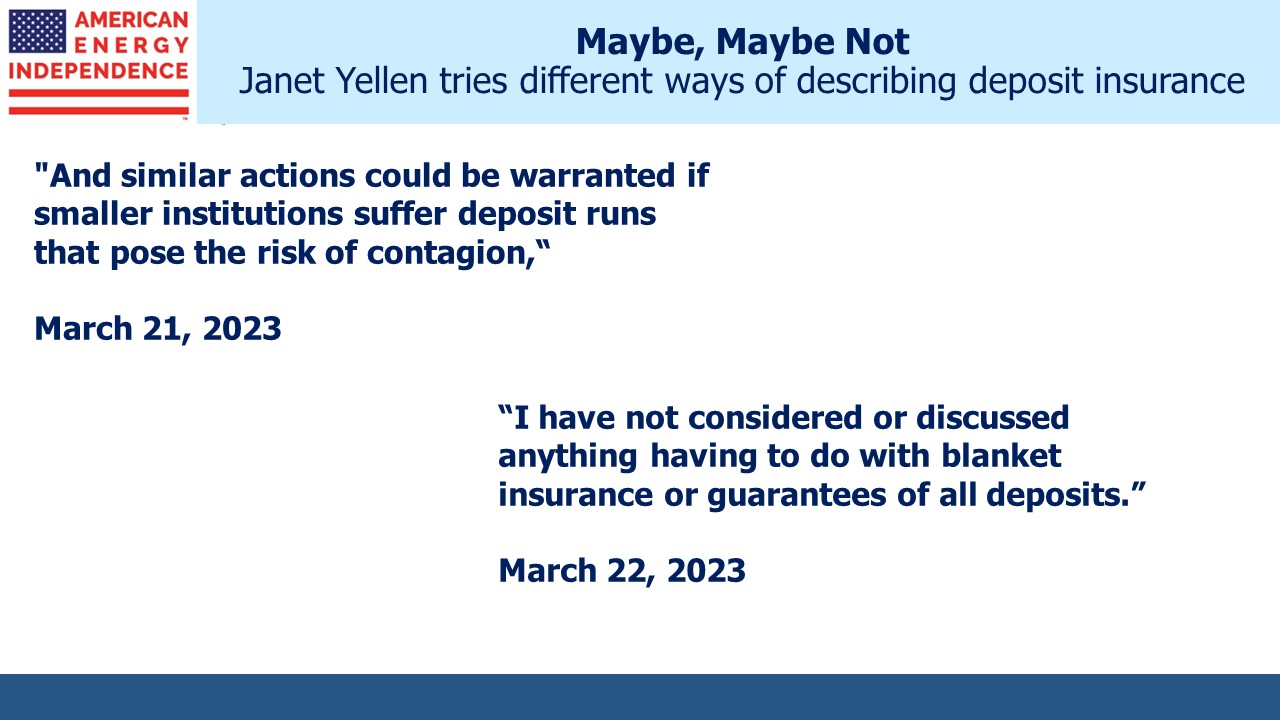

Extending FDIC insurance requires legislation, so Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen makes confusing pronouncements. Unable to explicitly guarantee every deposit, she nonetheless leaves the impression that she would.

There are increasing signs that regional banks, those not deemed too big to fail but nonetheless enjoying an implicit guarantee of their deposits, are being squeezed on both sides. They’re being forced to offer depositors higher rates, since their customers are no longer as slothful. SVB’s failure started with customers leaving for higher rates.

On the asset side, the banking system’s increasing duration risk has become problematic given the Fed’s rapid tightening. SVB’s reach for yield ultimately rendered them insolvent. Although they were an outlier in unsecured deposits and interest rate risk, markets and regulators are now pondering the unrealized losses in bond portfolios across the system. Sticky deposits are normally believed to have increased in value when rates rise because of the lethargy with which banks increase the rates they’re paying. But today’s altered dynamic looks likely to force more competitive practices on banks.

Schwab is a good example. Last year they changed their default option for client cash balances to Charles Schwab Bank rather than money market funds. This allowed them to pay low rates and invest the cash in bonds, picking up the spread. This is similar to SVB, but Schwab wasn’t as reckless.

Nonetheless, in their earnings on Monday Schwab revealed that the size of deposit outflows had caught them by surprise, forcing them to borrow money at wholesale rates to fund their bond portfolio. Banks have long argued that revaluing their assets down in response to higher rates without recognizing the implicit higher value in sticky deposits presents an unfair, biased picture. But the problem is that the long duration of liabilities isn’t contractual, it’s just assumed based on history.

Commercial and Industrial loans have dipped in the past several weeks, a first sign of risk appetites being reined in. Banks know regulators will look more closely at duration risk on securities and loans, casting a chill on their willingness to extend credit.

This is what’s behind the gap between where the market expects Fed policy to go and the FOMC’s projections. Tighter financial conditions have increased recession risk. Such differences are usually resolved at the cost of the FOMC’s reputation for forecasting accuracy.

On a different topic, Texas is confronting the problems that come with being the leading state in windpower generation. Storm Uri in early 2021 that caused widespread power outages led some renewables champions to note that natural gas plants stopped producing along with windpower, and that it was incorrect to blame the debacle on intermittent power.

Nonetheless, the Texas state legislature has concluded that more natural gas power plants are just what is needed to prevent a repeat. Having subsidized windmills they’re now going to subsidize reliable power to stabilize the grid. The intermittency of solar and wind creates problems for systems that become too dependent on them. Note that they didn’t opt to invest in battery back-up to compensate for this shortcoming. Instead, lawmakers in Texas have concluded that reliable, dispatchable power is what’s needed.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: