Why the Shale Revolution Hasn't Yet Helped MLPs

MLP investors must wish they’d never heard of the Shale Revolution. The consequent growth in volumes of crude oil and natural gas seemed a fairly simple thesis for owners of volume-driven infrastructure assets. Increased demand for pipeline and storage capacity, for gathering and processing networks, ought to be good for the sector. But so far, a dramatically more productive domestic energy industry has driven MLP stock prices relentlessly lower. Moreover, the divergence between the energy sector and the broader averages is a common investor complaint – the truism that MLPs are a volume business and therefore rising volumes should be good isn’t reflected in recent returns.

Early last week the International Energy Agency (IEA) published World Energy Outlook 2017 which forecasts that the U.S. will become the world’s biggest Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) exporter by the mid-2020s, and a net oil exporter by the end of that decade. Other long term forecasts, including those from the Energy Information Administration, Exxon Mobil and Goldman Sachs are broadly consistent with the IEA. MLPs slumped anyway, perhaps oblivious to the report or maybe because of it.

The Shale Revolution, the paradigm driving America to Energy Independence, has not done much for investors. It’s pressured cashflows and balance sheets of formerly stable businesses. Few management teams seem able to pass up growth opportunities, and the consequent redirection of Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) from distributions to growth projects has alienated those wealthy Americans who accepted K-1s in exchange for steady, growing, tax-deferred income. The evidence of this is most clearly seen in the defiantly high yields of some securities. Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), with its 14% payout, reflects investor disbelief that payments will continue.

Since yield no longer convinces, consider Duke Energy Corp (DUK) which delivers electricity and natural gas to over 9 million customers across the southern and Midwest U.S. It operates a highly regulated, capital intensive business. Kinder Morgan (KMI) transports, treats and stores natural gas (including now LNG), natural gas liquids and crude oil in a highly regulated, capital intensive business. Debt:Equity at DUK is 5.6X and KMI is 5.3X, so they’re similarly leveraged. But KMI’s multiple to its Distributable Cash Flow (DCF, or Free Cash Flow less growth capex) is 8.8X. The analogous cash flow multiple for DUK is 13.2X (Net Income plus D&A minus maintenance CapEx). DUK is 50% more expensive on a cash flow per share basis. Furthermore, the value of the land and easements acquired for pipelines appreciates over time whereas power plants eventually depreciate to zero. In this regard, DUK’s $7B/year (11% of it’s market cap) in growth CapEx becomes much more concerning.

The Utilities sector has been strong this year, which has stretched valuations while energy, including infrastructure, has lagged. The question is why investors in DUK and other similar names don’t make what looks like a substantial valuation upgrade by switching from one highly regulated business to another. KMI long ago broke its contract with the original Kinder Morgan Partners investors. When you remove a slide titled “Promised Made, Promises Kept” (see What Kinder Morgan Tells Us About MLPs) there are consequences. Redirecting cashflow from distributions to growth projects necessitated the revision to its investor presentation and took them in search of new investors.

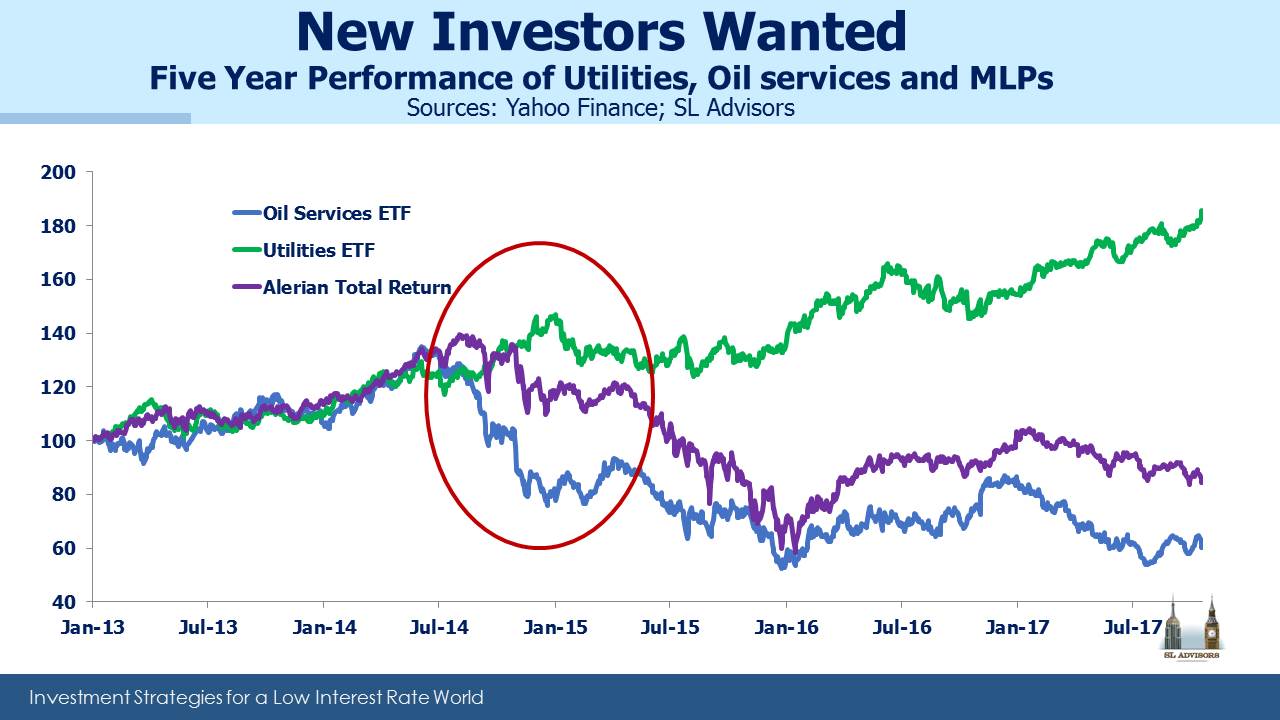

MLPs are a shrinking part of the energy infrastructure landscape. The Shale Revolution is leading us towards Energy Independence, increasingly through C-corps (hence our new American Energy Independence Index). But the sector moves nowadays with the Oil Services sector whose biggest names are struggling with a global slump in spending on conventional oil and gas projects, whereas in the U.S. the strength in volumes and spending continues. The close relationship between oil services and energy infrastructure is not likely to sustain over the long term given their substantially different business models (cyclical versus regulated; global versus domestic).

Recent weakness may also be due to concerns that tax reform could result in lower corporate tax rates with no improvement in rates charged on passive investment income from pass-through vehicles. This would benefit C-corps over MLPs — although details on the plan continue to change, there’s probably less certainty about the ultimate tax treatment for MLPs which could be causing potential buyers to wait for clarity. The news that Norway’s $1TN sovereign wealth fund is planning to divest its oil and gas holdings certainly didn’t help sentiment either.

Returning to the chart, it shows that as growth plans took hold through 2014-15, increasing secondary offerings (how you finance growth if you pay out all your cashflow in distributions) revealed the reluctance of traditional MLP investors to reinvest those payouts. This drove yields up and hurt sector performance. Although they got there in different ways, most big MLPs concluded that the growth capital wasn’t available and so cut payouts, redirecting cash to fund projects instead. Traditional MLP investors felt betrayed and are clearly not rushing to invest in the sector, which has created today’s value opportunity.