Russian Gas Exports Face An Uncertain Recovery

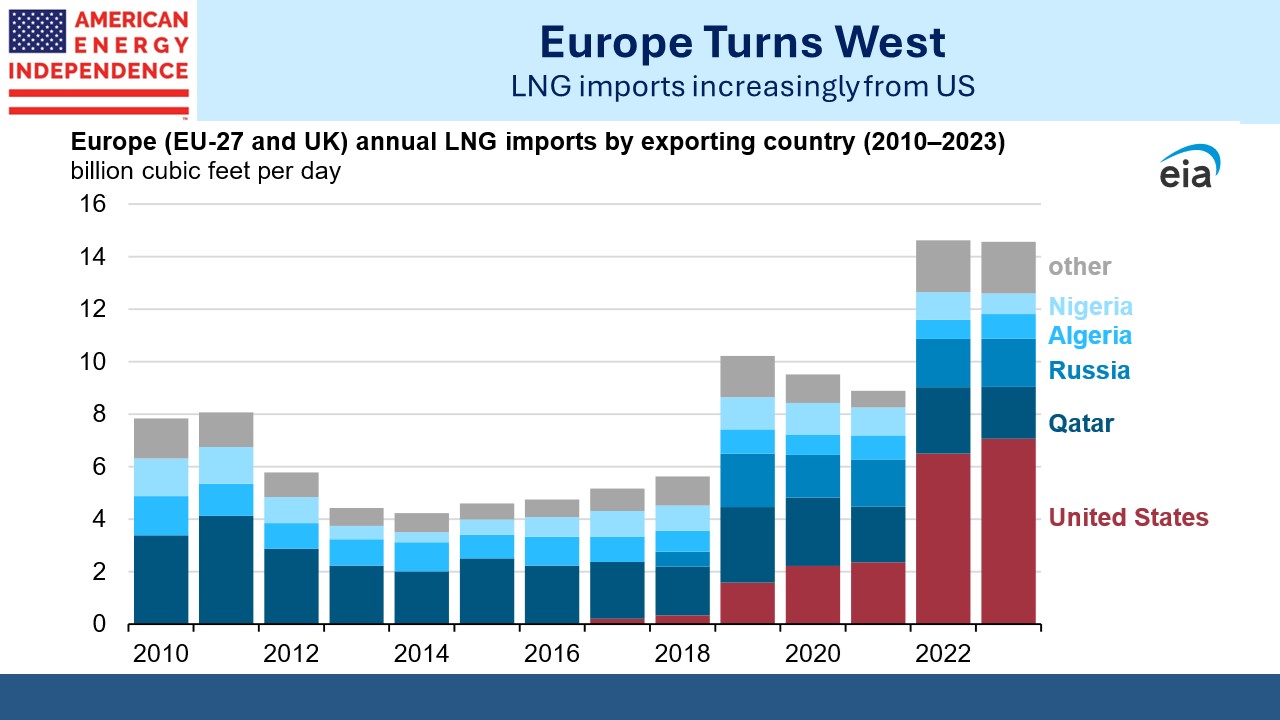

European imports of LNG rose sharply following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago. The US was well positioned to step in and provided virtually all the additional LNG Europe bought. The current pause on new LNG export terminals runs counter to these trade flows, but it’s increasingly clear this policy has few supporters other than some climate extremists.

Russia has had to pivot towards Asia and FSU (Former Soviet Union) buyers for its natural gas exports. In 2021 Russian exports via both pipeline and as LNG were 244 Billion Cubic Meters (BCM), around 23.6 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D). For reference, last year the US became the world’s largest LNG exporter, averaging 11.9 BCF/D.

Last year Russian exports were 142 BCM, down 42% over two years.

Returning gas exports to their previous level will take years if it occurs at all. Negotiations over the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline project with China are moving slowly, and there’s even a suggestion that Russia may begin construction of the pipeline before they have a signed agreement in hand. China clearly feels they have a strong hand to play – and yet China’s own energy strategy is to lessen its dependence on western supplies. Their booming EV market is one way to reduce the need for crude imports. Another is to align more closely with Russia, since on several levels they need one another.

Russia is also expanding its LNG export capability. The Novatek Arctic LNG 2 terminal with annual capacity of 27 BCM (2.6 BCF/D) may start operations as soon as this month. The US has threatened anyone providing “material support” with penalties or criminal prosecution. This apparently hasn’t dissuaded Philip Adkins, CEO of Red Box Energy Services, as described in this FT article.

Other projects that are less far along are vulnerable to sanctions as well as denied access to western liquefaction technology. Russian LNG projects have suffered timing delays. See Russia’s Gas Export Strategy: Adapting to the New Reality for more detail.

Last week the International Energy Agency (IEA) published CO2 Emissions in 2023. In recent years the IEA has moved from providing objective analysis of energy markets to promoting anodyne versions of the energy transition. Few of their projections on energy use are remotely plausible. As a result, some think if Trump wins the election he’ll stop funding the IEA, which seems to have outlived its purpose with its new approach.

The IEA reported that global energy-related CO2 emissions grew by 1.1% last year. Executive director Fatih Birol claimed that increased EV deployment over the past five years had constrained global oil demand, thereby reducing emissions. He overlooked that in the world’s biggest EV market Chinese electricity is 62% derived from coal. At the IEA, cheerleading sometimes beats analysis.

Canada announced that the TransMountain Expansion (TMX) pipeline that they purchased from Kinder Morgan (KMI) in 2018 (see Canada’s Failing Energy Strategy) will finally start operating. It connects oil-rich Alberta with Pacific export terminals in British Columbia.

TMX is planning 2.1 million barrels of linefill next month and another 2.1 in May. Construction has been a financial disaster for taxpayers, with the ultimate cost likely to exceed by 4X estimates when KMI deftly unloaded the project. Alberta has always struggled to get its oil to market. British Columbia’s left-leaning government has long been hostile to TMX, which prompted KMI’s sale. Keystone XL was intended to add southern takeaway capacity until Biden canceled it. Alberta’s oilmen will be relieved.

Canada also intends to expedite approval of new nuclear projects, a pragmatic step that acknowledges the limitations of solar and wind. The Sierra Club Canada is, like its US namesake, opposed to nuclear power. Climate extremists aren’t good for the rest of us.

Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) is often dismissed by those who want the world to rely on intermittent energy. Occidental is building the world’s biggest CCS facility in Texas and is optimistic about licensing the technology. They gave up on one project, named Century, after concluding the economics weren’t attractive enough. However, they drew a $550 million investment from Blackrock in Stratos, which is expected to be commercially operational by the middle of next year.

In Singapore, Exxon and Shell have formed a JV to work with the government on a CCS project. Opponents dislike CCS because it allows fossil fuels to be used without emitting CO2. This is why the rest of us should hope CCS becomes a vital part of the energy chain, since it will preserve our use of reliable energy rather than the intermittent, weather-dependent type.

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment: