Russia: The Climate Change Winner?

Higher prices for traditional energy are supportive of increased use of renewables. The point of a carbon tax is to create price signals for users and producers of coal, oil and gas that reflect society’s assessed cost of the burden imposed by rising CO2 emissions. Uncertainty over long-term public policy has led to years of underinvestment in new production. The economic rebound from Covid revealed how little excess supply was available, so prices rose. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a further shock the world didn’t need.

But the response from policymakers has been ambiguous. President Biden would rather ask Saudi Arabia to increase oil production than remove regulatory and policy uncertainty for domestic companies. The EU wants to import natural gas from Qatar but balks at twenty year commitments, even though Asian buyers regularly agree such terms. The result is that committing capital to oil and gas production remains an uncertain proposition.

Climate extremists should cheer today’s high oil and gas prices though. It improves the competitiveness of renewables. How ironic that the pursuit of intermittent energy has led to underinvestment in traditional energy and today’s elevated prices. A US carbon tax would have re-directed some of the revenue earned by OPEC+ to the Federal government, but political support is nonexistent because people are only worried about climate change until it costs money.

Energy security, Europe’s absence of which has been so cruelly exposed by Russia, is another reason to develop domestic renewables. Keeping the windmills nearby at least means their output can’t be cut off by a political adversary.

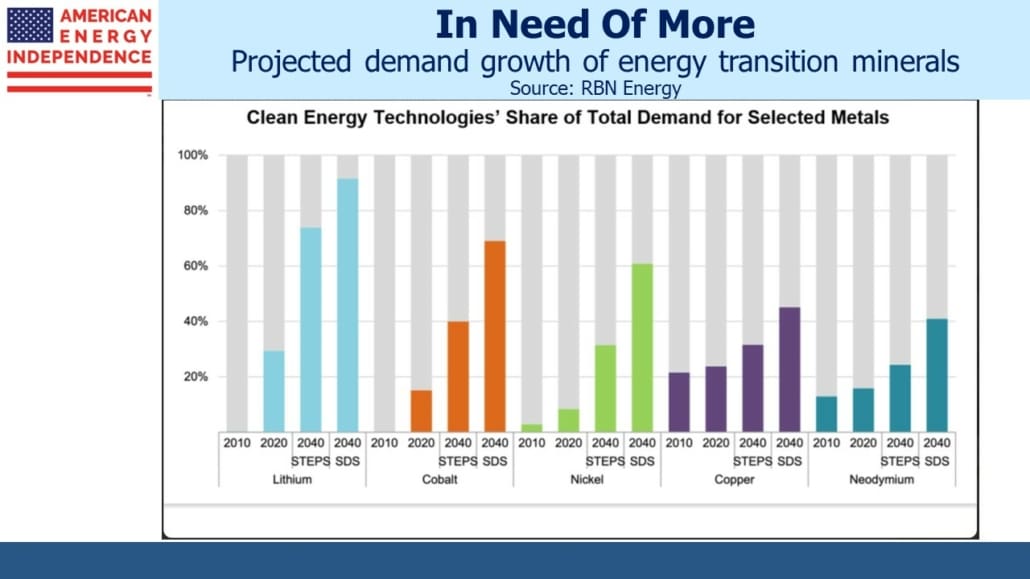

The energy transition means increased electrification. Serious analysis is being published that highlights the challenges. In the Internation Energy Agency’s (IEA) most recent World Energy Outlook they model a Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) which is based on current policy settings around the world, and a Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) which aligns with the UN IPCC’s goals whereby the world reaches net zero emissions by 2070 with many countries much earlier.

RBN Energy, which produces in-depth research on the energy sector, has translated these two IEA scenarios (STEPS and SDS) into demand for minerals key to the energy transition, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and neodymium. Even on the less ambitious STEPS pathway, these minerals will represent a significantly greater share of global demand.

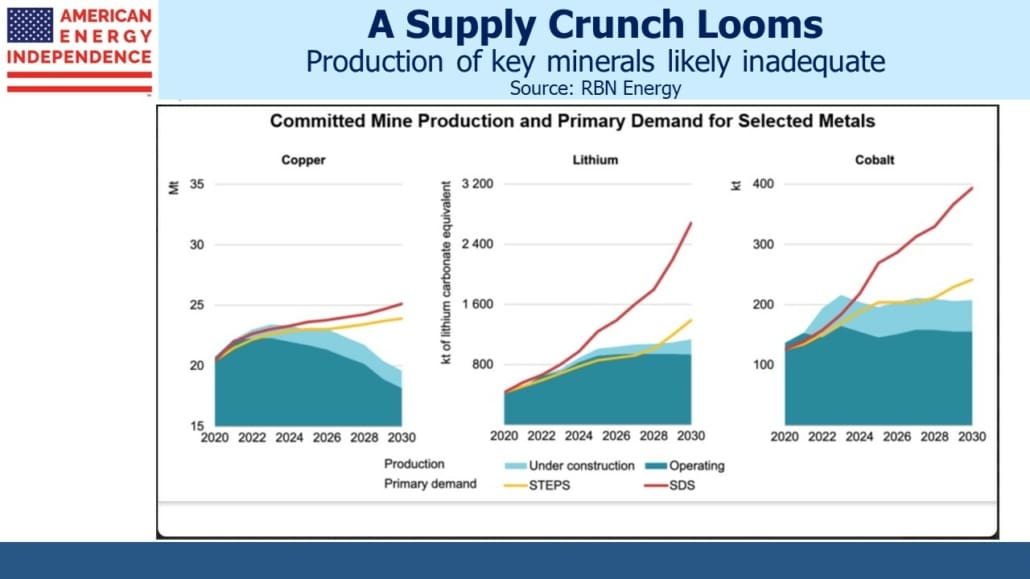

The time it takes to get a new mine from planning to production is longer than for oil and gas fields – a global average of sixteen years according to research from the IEA. On current trends, there will be an increasing supply shortfall for these key minerals. There’s no shortage of irony in such research. Energy (mostly oil and gas) can account for up to 40% of the total costs in mining. Although higher prices for traditional energy have a positive first order effect on renewables, they also raise the cost of obtaining the needed inputs for batteries, solar panels and windmills. The US is poorly positioned for this, dependent on imports for 100% of some 17 critical metals and minerals. Mining meets NIMBY resistance. As RBN Energy eloquently states: The simple fact is that the U.S., along with Europe, has regulated its way into far greater mineral import dependencies.

Vaclav Smil, a world-class author of books on energy, noted the mining needed for a single Electric Vehicle (EV) car battery weighing 450 kilograms (992 pounds). In How the World Really Works, Smil calculates that the lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, graphite, steel, aluminum and plastic required for one EV would require the mining of 40 tons of ores and 225 tons of raw materials. Achieving an EV market share of 25% of the global auto fleet by 2050 would see demand for these and other inputs increasing by 15X or more.

California leads the US in embracing EVs, often cheered on by media that believes such policies will reduce the statewide fires, drought and floods they often blame on global warming. They overlook that policies in Beijing and Mumbai, where emissions are scheduled to grow for at least the rest of the decade, will determine California’s CO2 levels (and indeed everyone’s) far more than the legislature in Sacramento.

JPMorgan’s Mike Cembalest in his excellent 2021 Annual Energy Paper called out “the elephant in the room: the number one issue for China and the world is decarbonization of China’s massive industrial sector, which consumes 4x more primary energy than its transport sector and more primary energy than US and European industrial sectors combined.” In other words, widespread adoption of EVs creates great headlines but won’t make much difference.

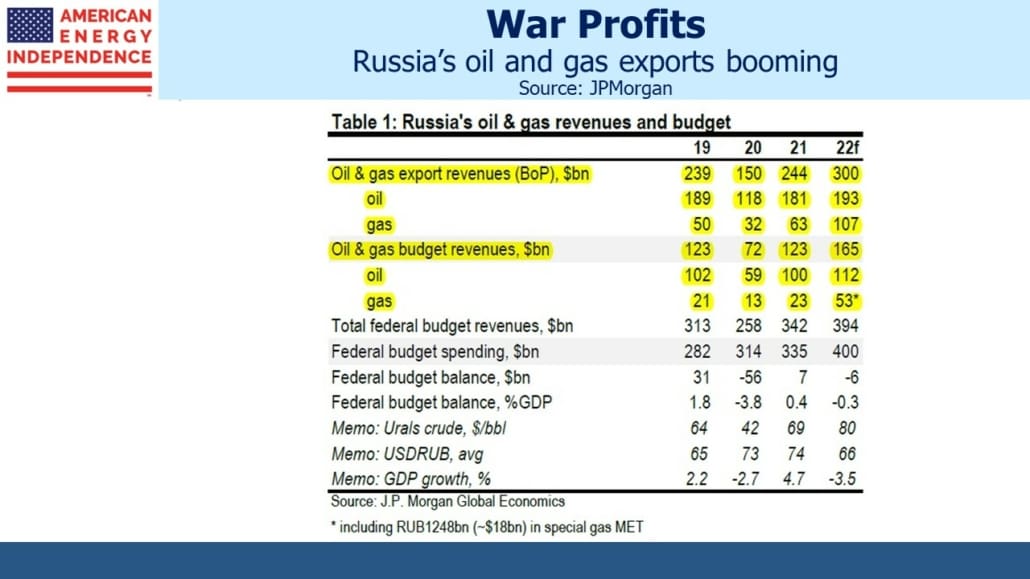

Which brings us to the final irony. There is little to show so far for western sanctions on Russia. Their oil and gas revenues are soaring. Asian buyers freely ignore sanctions, and a humiliated Europe is slowly reducing imports so as to limit economic disruption. Russia looks likely to cut gas supplies anyway. This is Angela Merkel’s legacy.

Western policies that have discouraged investment in future oil and gas production align neatly with Russia’s vast supplies. Eight years ago NATO accused Russian intelligence agencies of covertly funding the European anti-fracking movement. It always seemed like a high return effort. But even if such charges are unproven, Russia is a top copper producer (4% of global supply, roughly equal to the US), 6% of the world’s aluminum (4X the US), and 10% of nickel (#3 in the world). Russia, one of the countries least concerned about climate change, might be one of its biggest winners.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.