Rising Rates and MLPs: Not What You Think

Five years ago my book Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors argued that interest rates were likely to stay lower for longer. Excessive debt led to the 2008 Financial Crisis, and our thinking was that low rates were part of the necessary healing process, allowing the burden of debt to be managed down.

Rates have indeed remained low, helped by the Federal Reserve’s very measured steps to “normalize” the Federal Funds rate with periodic hikes. Most forecasters, including the rate-setting members of the Federal Open Market Committee, have consistently expected rates to rise faster than they have.

Nonetheless, ten year treasury yields have been drifting up and recently touched 2.6%. Unemployment remains very low if not yet inflationary. GDP growth and corporate profits are strong. The recent tax changes are fiscally stimulative. Bill Gross has declared that we’re in a bond bear market, and Jeffrey Gundlach sounds equally cautious. It’s likely that this will be an increasing topic of conversation among investors.

We have no view on the near-term direction of bond yields, beyond noting that current yields are too paltry to justify an investment. It’s been a long time since bonds looked attractive. As we noted in our 2017 Year-end Review and Outlook, interest rates are what make stocks attractive. The Equity Risk Premium (S&P500 earnings yield minus the yield on ten year treasury notes) favors stocks, but if rates rose 2% bonds would offer meaningful competition. Although a 4-4.5% ten year treasury yield is a long way off, the historic real return (i.e. yield minus inflation) going back to 1928 is 1.9%. So 2% above an inflation rate of 2% that’s rising wouldn’t be historically out of line.

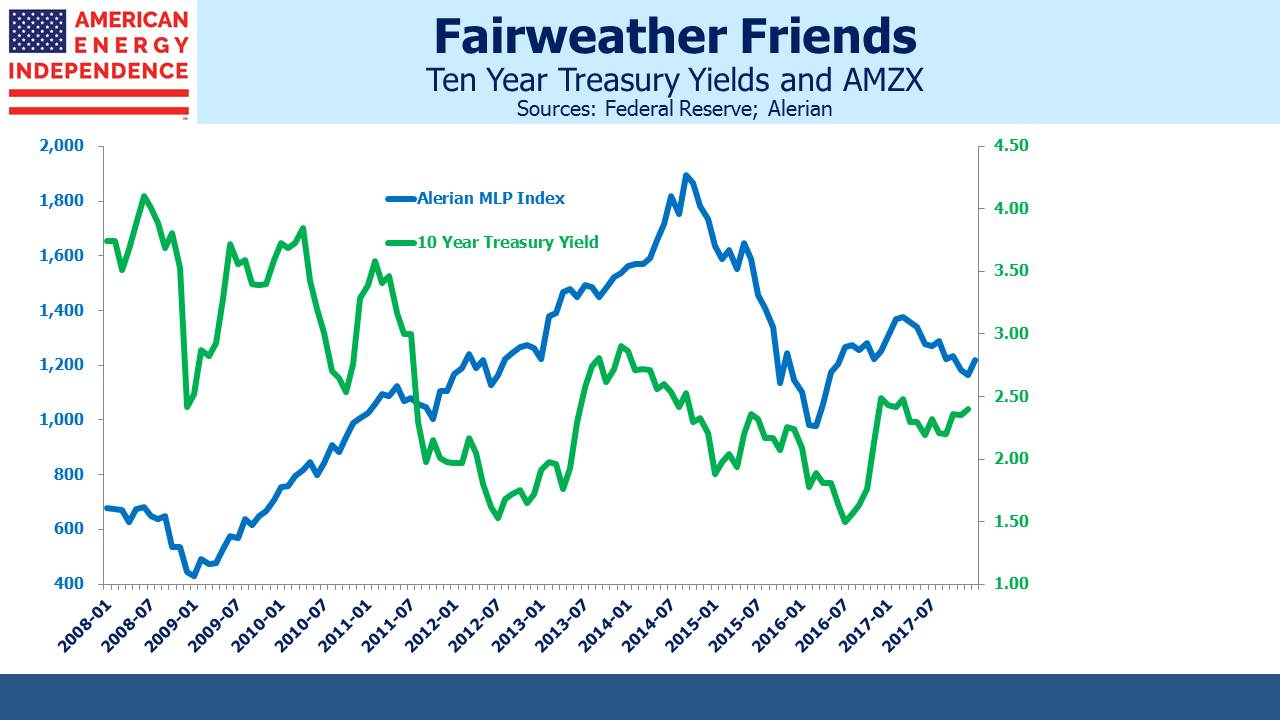

Energy infrastructure investors will begin considering how rising rates might affect the sector. Traditionally, MLPs were categorized as an income-generating asset class along with REITs and Utilities. Rising bond yields have in the past represented a headwind for all these sectors, although MLP cashflows are not that sensitive to rate movements. Debt is predominantly fixed rate, and certain elements of the business, such as pipelines that cross state lines, operate under highly regulated tariffs which include annual inflation-linked increases.

But energy infrastructure has undergone substantial changes over the past three years. Although yields are historically attractive, the volatility of 2015-16 was inconsistent with the stable, income-generating asset class investors had sought. As we’ve noted before (see The Changing MLP Investor), the Shale Revolution created growth opportunities that upset the business model and led many MLPs to “simplify,” their structure, which in practice meant they cut distributions in order to finance new investments. Consequently, the path of U.S. hydrocarbon production growth is more important than in the past.

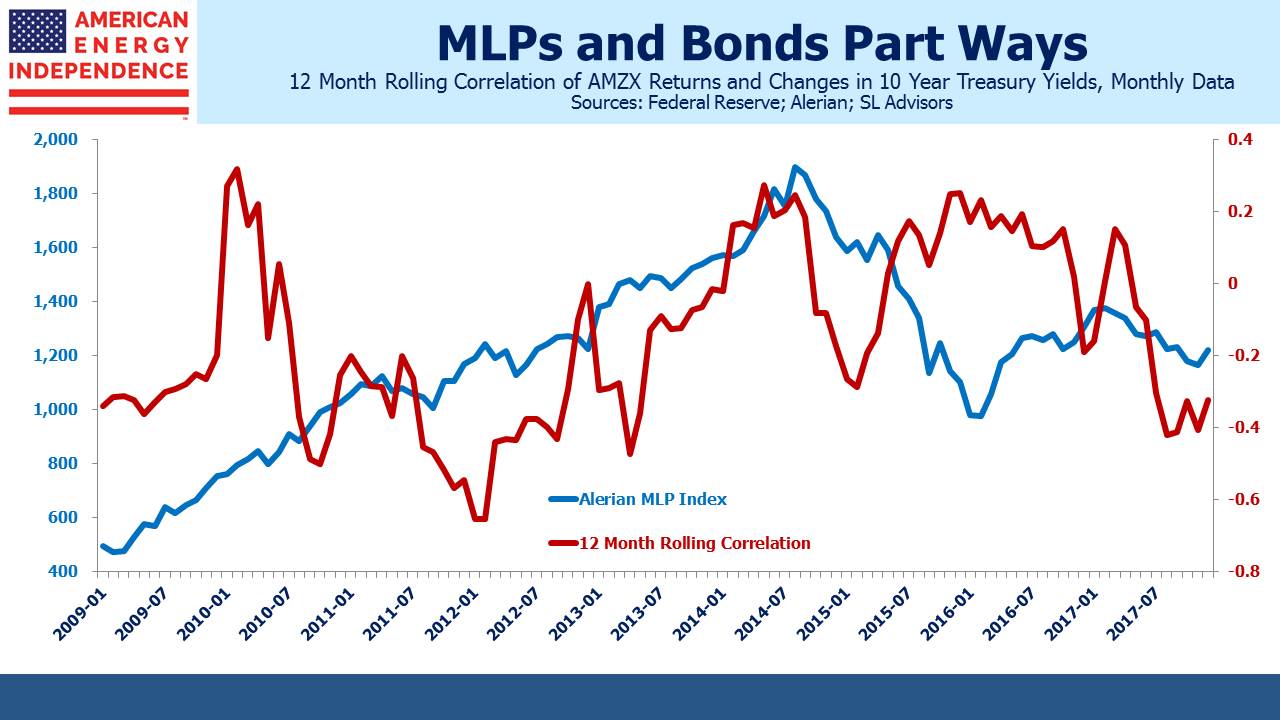

The long term relationship between MLPs and treasury yields is not a stable one. The correlation between rate changes and MLP returns has fluctuated over the years, reflecting that there’s a weak economic connection between the two. Initial moves up in rates have often led to short term weakness in energy infrastructure, probably due to competing fund flows as noted above with REITs and Utilities. However, recent bond market weakness has led to the opposite result. The correlation is becoming negative.

This is likely because the strengthening economy, which is driving up rates, is improving the outlook for the energy sector as well. Energy infrastructure is more sensitive to volume growth, since this increases capacity utilization of existing facilities as well as the likelihood of further growth. A stronger economy will, at the margin, consume more energy. The 12 month rolling correlation (through December 2017) is the most negative it’s been since the sector peaked in August 2014. In January this relationship has persisted, with rates and MLPs both moving higher. So far, the economic forces that are causing weaker bond prices have been positive for energy infrastructure.

The investable American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) finished the week +1.9%. Since the November 29th low in the sector, the AEITR has rebounded 13.9%.