Renewables Confront NIMBYs

Last week a Federal judge blocked completion of the Cardinal-Hickory Creek high-voltage transmission line. The 102-mile project linking Dubuque County, Iowa, to Dane County, Wisconsin has one mile remaining. Three environmental groups opposed its construction through a Mississippi River wildlife refuge. It’s needed to upgrade an existing transmission line built in the 1950s, add capacity, and bring new solar and wind power to Madison, WI.

Environmentalists are far from one homogeneous group. Locally, they can oppose infrastructure enabling the energy transition they support nationally. An FT video on the Cardinal-Hickory Creek website shows an environmentalist holding a feather (“I found five today”) lost by a bird unsuccessfully navigating the pylons.

Power lines are an unfortunate ugly corollary to electricity use. Because solar and wind need large spaces, their output must travel long distances to customers. Climate extremists wishing to project a coherent view must reconcile the two. Nuclear and natural gas take up less room so can be placed nearer their customers.

The big problem with energy infrastructure isn’t the opposition from environmentalists. It’s the legal process that allows last-minute delays to projects that are almost complete.

Cardinal-Hickory Creek was first conceived in 2011. Public engagement began in 2014, authorizations were in hand by 2020 and construction began in 2021. 115 renewables projects with 17 gigawatts of capacity depend upon its completion. Nobody will build anything that can be derailed at the finish line when capital has been long committed and spent. But this is America’s process today.

We’re suddenly moving into a period of high demand growth for electricity following decades of flat demand. Electrification, including increased use of EVs was expected to add 1% pa to demand. Data centers are suddenly the new power hogs.

Wells Fargo estimates that AI will add 16% to US power demand by 2030. In less than a year, 1% annual demand growth has become 3%+.

For some this will increase the urgency to add even more solar and wind, although it’s hard to imagine that we could be doing any more. Therefore, it will boost natural gas demand.

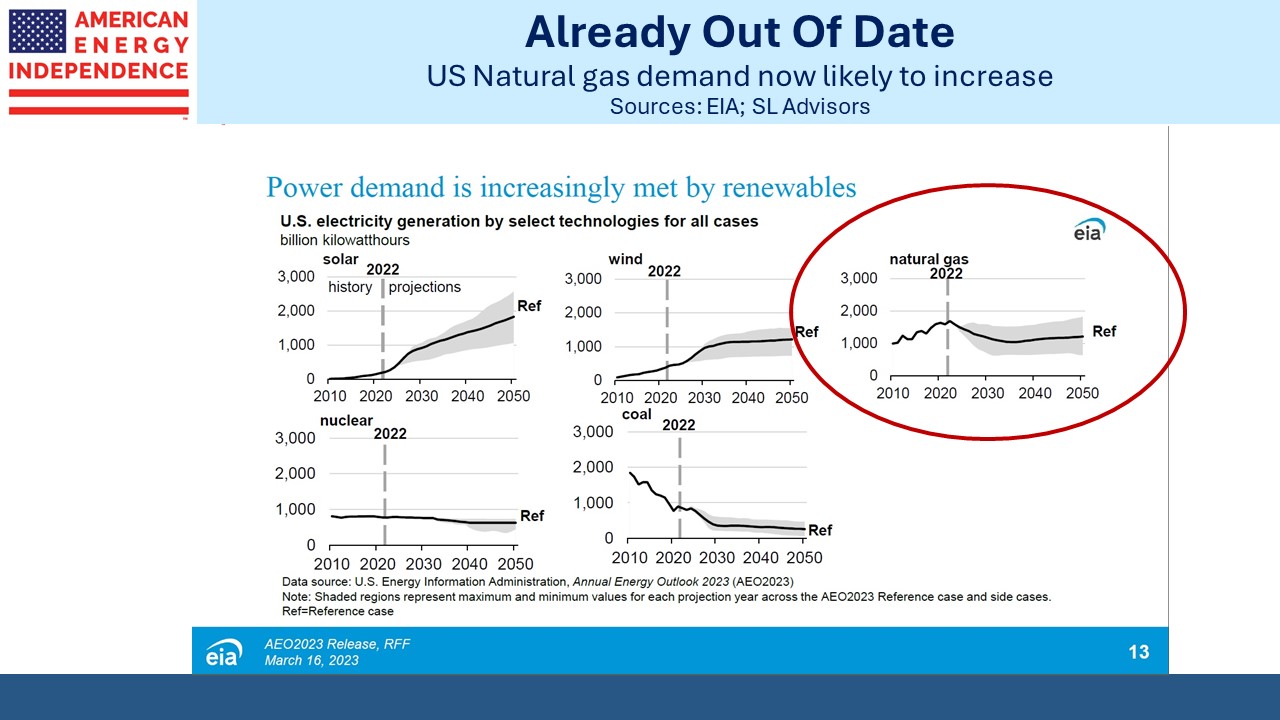

Last year the Energy Information Administration (EIA) projected natural gas use in electricity generation was about to peak. The EIA produces unbiased research, unlike the International Energy Agency (IEA) whose publications are mostly fantasy appealing to climate extremists.

This loss of demand will be made up for elsewhere in industry and via LNG exports once the pause on new permits is lifted. But now the trajectory has changed. Wells Fargo estimates that AI will boost natural gas by 7 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D) in order to meet just 40% of the incremental power load. Their upside case is 16 BCF/D. Last year the US produced 105.5 BCF/D from the lower 48 states.

This analysis only considers US data centers. But they’re being built all over the world. The AI revolution is global. Projected increases in electricity generation will add to global LNG demand. US natural gas prices are cheap. Chad Zamarin, a senior vice president at Williams Companies (WMB) says, “Domestic U.S. markets are oversupplied.”

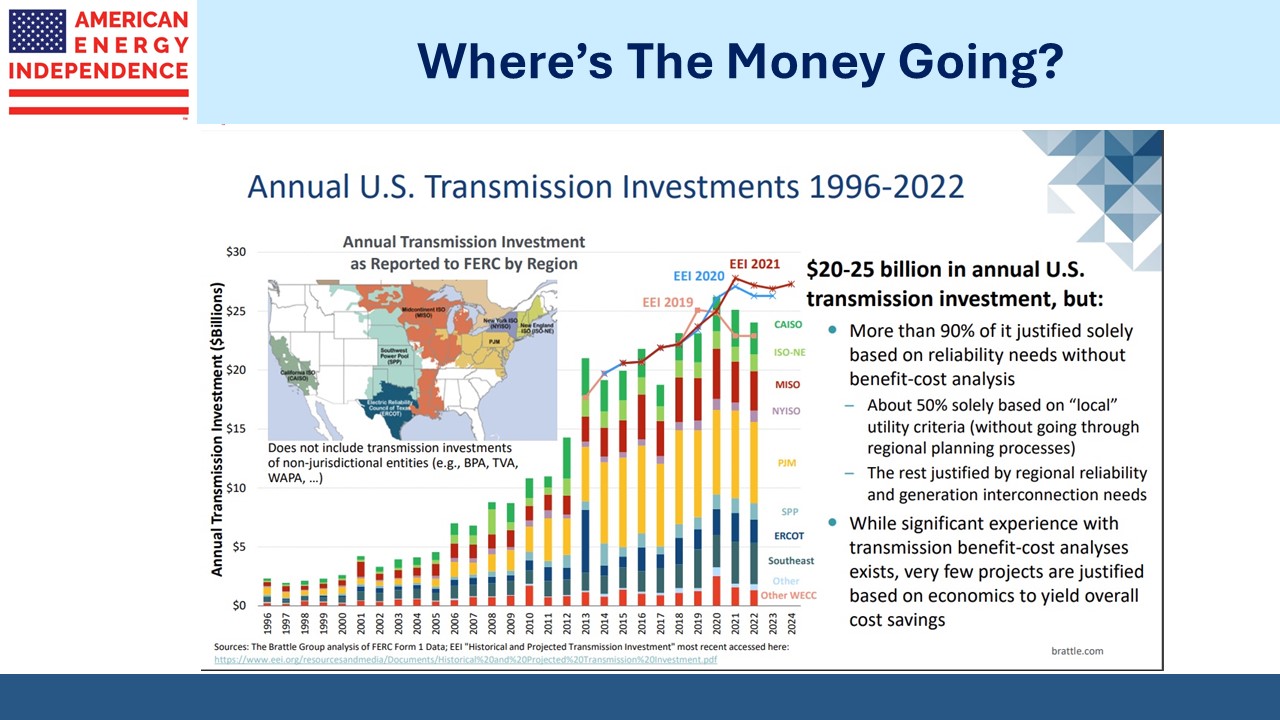

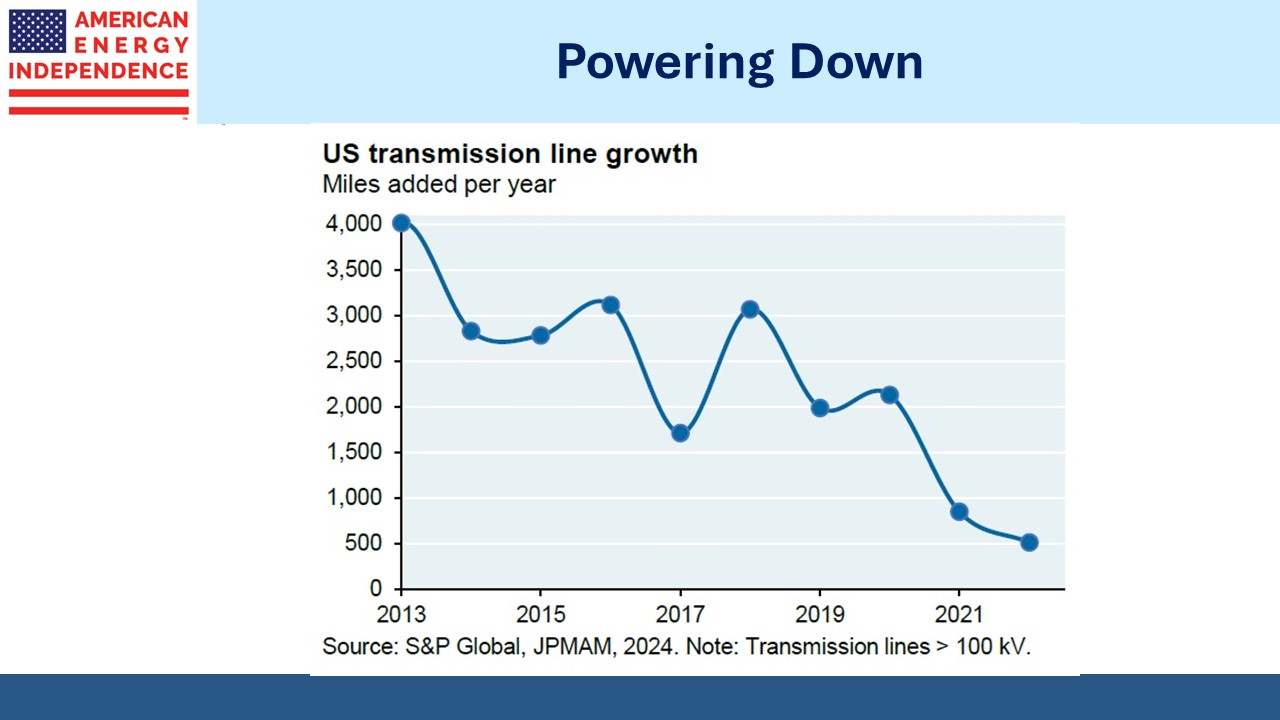

Companies that produce electrical equipment should do well. Transformers are on a two year backlog. But assuming this will be good for renewables is to bet on a transformation of how infrastructure gets built.

America’s regional grids are increasing spending. But we’re adding the fewest miles of transmission in a decade. This is the morass into which investors in clean energy and utilities are jumping. Regardless of how strongly you believe in renewables and how sleepless rising sea levels make you, financing solar, wind and new power lines looks like a good way to lose money.

Morocco’s Noor Ouarzazate solar complex, operated by Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power International, has had to shut down for most of the year because of problems at its storage unit. The facility has suffered repeated problems. A government agency called for its closure in 2020 because of high cost.

Morocco has a goal of getting renewables to half its power capacity by 2030. Their primary energy consumption is 7% renewables, with the balance from fossil fuels. Give them credit for trying. Many Moroccans would likely prefer adding cheap energy over green energy to raise living standards. Per capita energy consumption is a tenth of the US.

It seems increasingly clear that the AI revolution is going to boost natural gas consumption. Adding new pipelines is no easier than adding power lines. But pipeline operators can add small amounts of capacity at the margin. They don’t face any new competitors. Toby Rice, CEO of EQT, said, “Our pipeline infrastructure is maxed out.”

Rather than being compelled to deliver the energy transition, natural gas pipelines are positioned to compensate for the transition’s inability to deliver what politicians have promised.

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment: