Prospects Continue to Brighten for U.S. Energy Infrastructure

A few seemingly unrelated pieces of news caught our attention last week. Together, they provide a useful perspective on why U.S. energy infrastructure offers such an attractive return potential.

Khalid al-Falih, Saudi Arabia’s Energy Minister, warned of a looming shortage of crude oil with the risk of a consequent price spike. This may seem like an odd concern given last year’s collapse in prices, but the Saudis are looking farther ahead than the drawdown of existing stockpiles. He recognizes that the $300-400BN slashed from drilling budgets this year, and the estimated $1TN cut through 2020, will lead to much less new supply coming online than might have been the case had oil stayed at $100 a barrel where it was in 2014. There’s a substantial time lag between committing to a new project and producing oil. Volatile prices hurt demand, and are therefore not in the interests of suppliers either. We wrote about precisely this issue in Why Oil Could Be Higher for Longer.

However, Rex Tillerson, Exxon Mobil (XOM) CEO, offered a contrasting view based on the resurgence in shale output in the U.S. being capable of responding to higher prices with increased output. Unlike conventional oil projects with their large upfront investment and long payback times, shale drilling involves numerous fairly cheap wells and high initial production. This means payback times are shorter and production can be quickly curtailed when prices are adverse (see Why the Shale Revolution Could Only Happen in America). On their recent earnings call, Haliburton CEO Dave Lesar said, “…North America has assumed the role of swing producer in global oil production.”

Either of these views on oil could be right. In each case, it will be good for U.S. producers and their infrastructure providers.

Related to this, there’s a growing disconnect between falling capital expenditure (capex) by companies drilling for hydrocarbons and their rising production. Antero Resources (AR) has cut capex by 20% since last year while production is up 14%. EQT Corporation cut capex 41% and raised production by 31%. Consol Energy (CNX), -74% and +16%. Exploration and production companies (E&P) are managing substantial improvements in efficiency, which speaks to Rex Tillerson’s comments above.

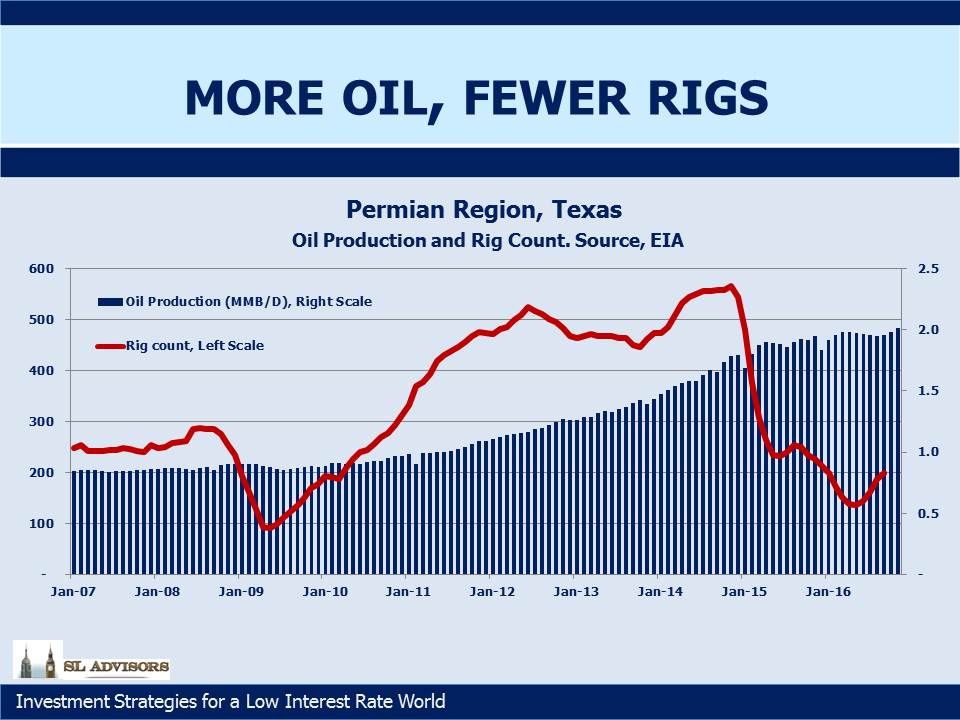

The chart above shows what’s happened in the Permian Basin in Texas, currently one of the most productive regions in the U.S. Using data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the rig count fell 75% from September 2014 to May 2016 while production increased 19% over the same period, representing a dramatic improvement in efficiency and lower break-evens for E&P companies. This is pointedly not what the Saudis expected when they increased output in 2014 so as to expose the weak business models of shale drillers.

Finally, a few weeks ago (see There’s More to Pipelines Than Oil) we noted a documentary made in the 1950s about the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line, later called Transco and today owned by Williams Companies (WMB). It’s worth watching. In 1931 the Natural Gas Pipeline Company of America built a transmission pipeline from Texas and Louisiana to Chicago. It is still in use today, owned by Kinder Morgan (KMI). Properly maintained, infrastructure lasts a long time – far longer than the depreciation schedules used under GAAP accounting, which is why net income is generally less useful than cashflow less the cost of maintenance (Distributable Cashflow, or DCF) in measuring performance. GAAP Depreciation, a non-cash expense, depresses net income and understates the cash flow generating capability of an asset that doesn’t depreciate according to a GAAP schedule. Pipelines more typically increase in value over time, because they’re hard to replicate. On KMI’s earnings call on Wednesday, chairman Rich Kinder noted the challenges in building certain new projects such as in New England because of the regulatory environment, but added, “…to the extent it becomes difficult to build new infrastructure, that tends to make existing pipeline networks more valuable.”

U.S. energy infrastructure remains one of the most interesting places to invest.

We are invested in KMI and WMB.