Pipelines Will Last Longer Than Equity Prices Imply

An enduring dichotomy in the valuation of midstream energy infrastructure companies has been the sharply different outlooks implied by debt versus equity pricing. Dividend yields of 6-7% suggest equity investors don’t regard their payouts as being sustainable indefinitely. Contrast that with investors in long term bonds, who accept yields of under 4% that can only be justified by a far more optimistic outlook about asset longevity. One camp presumably thinks the energy transition will leave pipeline companies with stranded assets, and the other believes the transition will not have harmed their prospects of principal repayment over the next three decades.

Equity investors probably don’t use years of remaining useful life as an input to valuing pipeline stocks. But their collective actions do imply such a judgment. In effect, the equity prices of pipeline companies imply that bond investors will lose their seniority in the capital structure before maturity. If Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) will exhaust the company’s ability to pay its owners before long term bonds mature, those bond investors will wind up owning equity. How long will this take?

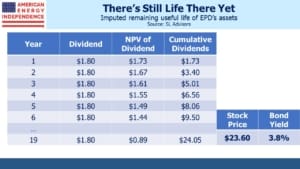

It turns out there’s a neat way to estimate this. The table below shows how this works for Enterprise Products Partners (EPD). It uses dividends because they’re easily identifiable, and therefore produces a more conservative (i.e. longer) useful life than using FCFE since companies are not paying out more than their FCFE in dividends nowadays.

Equity investors who have carefully considered buying EPD before ultimately rejecting it have concluded that the dividend will not last indefinitely. Therefore, they must regard the yield on EPD’s 30-year bonds as wholly inadequate for a fixed income investment, and that ultimately bond holders will own the equity when the existing common shareholders are wiped out. Since the bond yield is what the eventual owners need as compensation for this outcome, it can be used as the discount rate on future years’ FCFE. Adding up the successive years of FCFE until its value equals the price paid (i.e. today’s equity price) reveals when equity investors by implication expect those cashflows to stop.

For EPD equity investors, discounting the company’s $1.80 annual dividend back at the 3.8% yield on its 30-year debt means that today’s stock price reflects the NPV of 19 years’ worth of dividends. The company’s 7.6% dividend yield projects that today’s equity investors will be wiped out and replaced by bond holders, who will become the new owners of EPD, at that time.

This seems to us an unreasonably pessimistic view of the remaining useful life of the company’s assets. We’re also assuming no growth in dividends or giving credit to buybacks even though EPD has a buyback program in place which is returning additional value to equity investors. The implied useful life is even less than 19 years to the extent dividend growth and buybacks occur.

EPD bond investors fully expect to be repaid in full, and don’t anticipate owning the company. EPD’s stock price implies the opposite. It would be interesting to listen to a conversation between a well-informed non-buyer of EPD’s stock and one of their bond holders.

The math produces similar results for other big pipeline companies. Kinder Morgan’s (KMI) 29 year remaining asset life is longer than the others because its dividend is more generously covered. KMI slashed its dividend in 2015 and began cautiously increasing it in 2018. It has plenty of room to grow.

Environmental extremists would likely cheer the dour outlook reflected in pipeline stock prices. Last week the International Energy Agency (IEA) published a report laying out how the world could reach net zero energy-related emissions by 2050. It relies on some bold assumptions, such as no new investment in coal, oil or gas production starting now. It also incorporates significant behavioral changes including slower speed limits on highways, warmer settings on air conditioners and a 35% reduction in the percentage of households owning at least one car compared with current trends.

As usual the media covered the report’s release favorably. The Financial Times published three articles within 24 hours (Why the IEA is ‘calling time’ on the fossil fuel industry, Energy groups must stop new oil and gas projects to reach net zero by 2050, IEA says, and The IEA has delivered an overdue message). This is how pipeline equities are priced.

More representative of the view held by bond investors was Reuters, with Asia snubs IEA’s call to stop new fossil fuel investments. Although the energy transition will continue to impact everyone, the IEA’s report is more aspirational than plausible.

Even following this year’s rally, pipeline stocks reflect an expectation of stranded assets that bond investors, and many others reject. The sector is still cheap.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: