Oil Forecasters Have to Work Harder

Those in the oil industry who take a long view increasingly worry about insufficient new supply. It’s hardly today’s problem, with crude oil back to the mid $40s as OPEC’s production cuts are offset by increased shale output. But depletion of existing fields is generally believed to take 3-4 Million Barrels a day (MMB/D) off the market every year and demand continues to increase by 1-1.5 MMB/D annually. As a result, 4-5MMB/D of new supply is required annually to balance the market. Global production is currently around 97 MMB/D.

Last week Amin Nasser, chairman of Saudi Aramco, noted that the 20 MMB/D of new production thus needed over the next five years is unlikely to be forthcoming from U.S. shale, or indeed anywhere else. The International Energy Agency (IEA) offered a similar outlook.

The short-cycle nature of shale is likely impeding new development. In the past, the supply response function of crude was quite slow in reacting to demand changes, which contributed to some extreme price volatility. Since bottoming 18 months ago crude has been more stable. The ability of shale producers to alter production in just a few weeks or months is contributing. It also means that backers of a new, conventional project have to consider the impact on their returns from a repeat of the 2015 oil collapse, since much of the U.S. shale industry was able to protect itself by reducing output.

In the competition between short-cycle and long-cycle, the former’s flexibility represents a significant advantage. It means some projects that might ultimately turn out to be profitable aren’t getting approved.

This is one of the reasons that JBC Energy forecasts an extra 1MMB/D of shale oil output by the end of next year. This would take overall U.S. crude output over 10 MMB/D, to around the same level as Saudi Arabia.

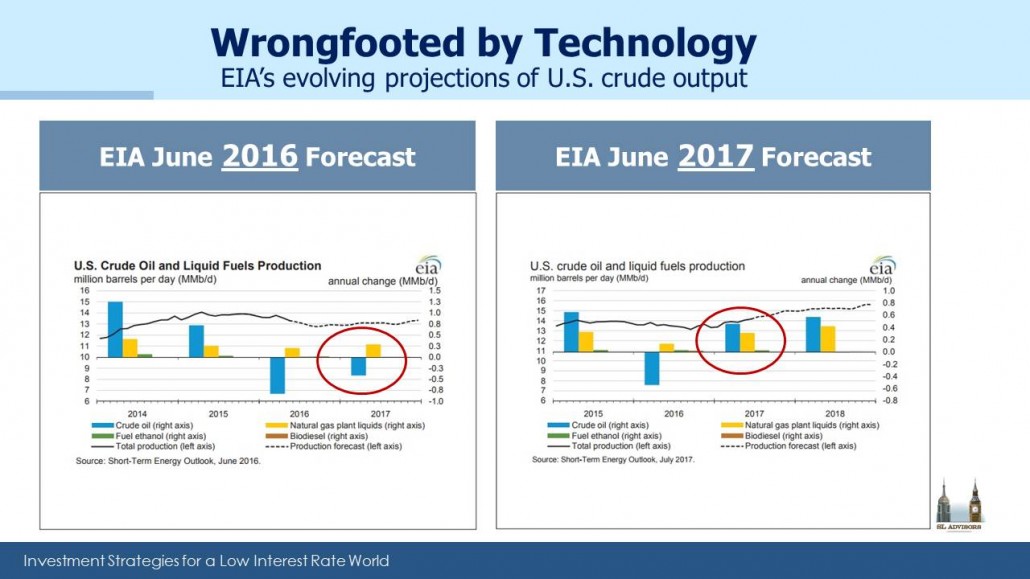

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), agrees, recently projecting 9.9 MMB/D of average output next year which would correspond with JBC Energy’s 10 MMB/D 2018 exit rate. This will be the highest annual average production in U.S. history, surpassing the previous record of 9.6 MMB/D set in 1970. It’s worth noting that one year ago the EIA was forecasting a decline of 0.4 MMB/D to 8.2 MMB/D for 2017 production, while they’re now projecting a 0.6 MMB/D increase to 9.3 MMB/D. The size of the 1 MMB/D revision over twelve months reflects the dramatic improvements in productivity across the industry (and maybe, ahem, poor forecasting).

A recent example is Devon Energy’s record breaking well drilled in Oklahoma which produced 6,000 barrels a day equivalent of oil and gas during its first 24 hours of operation.

U.S. shale output is set to grow and is becoming the swing producer, quickly responding to price signals and as a result keeping oil prices in a fairly narrow range. Prices may be lower than producers globally would like, but they’re high enough to stimulate increased domestic production, which is what the owners of midstream infrastructure care about. Impressive as these gains are, they’re not going to meet the supply shortfall that Saudi Aramco’s Nasser and others see on the horizon. But it’s hard to see how that problem can be anything but good for the U.S. and MLPs.