LNG Keeps Growing

Conflict in the Middle East invariably leads to concern about disruption to crude supplies that pass through the Strait of Hormuz. Oil prices duly rose once Israel launched its surprise attack on Iran. Around 20% of total oil consumption comes through this narrow waterway. It’s unlikely Iran could close it for long if at all.

Sell side firms have estimated that the market’s assessed probability of a closure is around 15-20%, based on comparing the recent move up in crude versus where it would go if a fifth of global supplies were stopped. Crude is up about 20% this month.

Around 20% of the world’s Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) also passes through the same bottleneck. Nonetheless, the reaction of regional LNG benchmarks in Asia and Europe, where most imports go, has been muted, with prices rising around 3% this month.

Maritime insurance rates have gone up, and ships are being asked to arrive at export terminals in the Arabian Gulf only when called to minimize the number of vessels concentrated together.

Although 20% of oil and LNG pass through the Strait, LNG is only 14% of global gas consumption. This explains the difference in market response to the Israel-Iran war, since only 3% of the world’s gas is at risk.

Oil is easier to move than gas, so around 40% of the world’s oil is traded before being refined. Because natural gas isn’t very energy-dense, its volume has to be significantly condensed to make movement by ship commercially attractive.

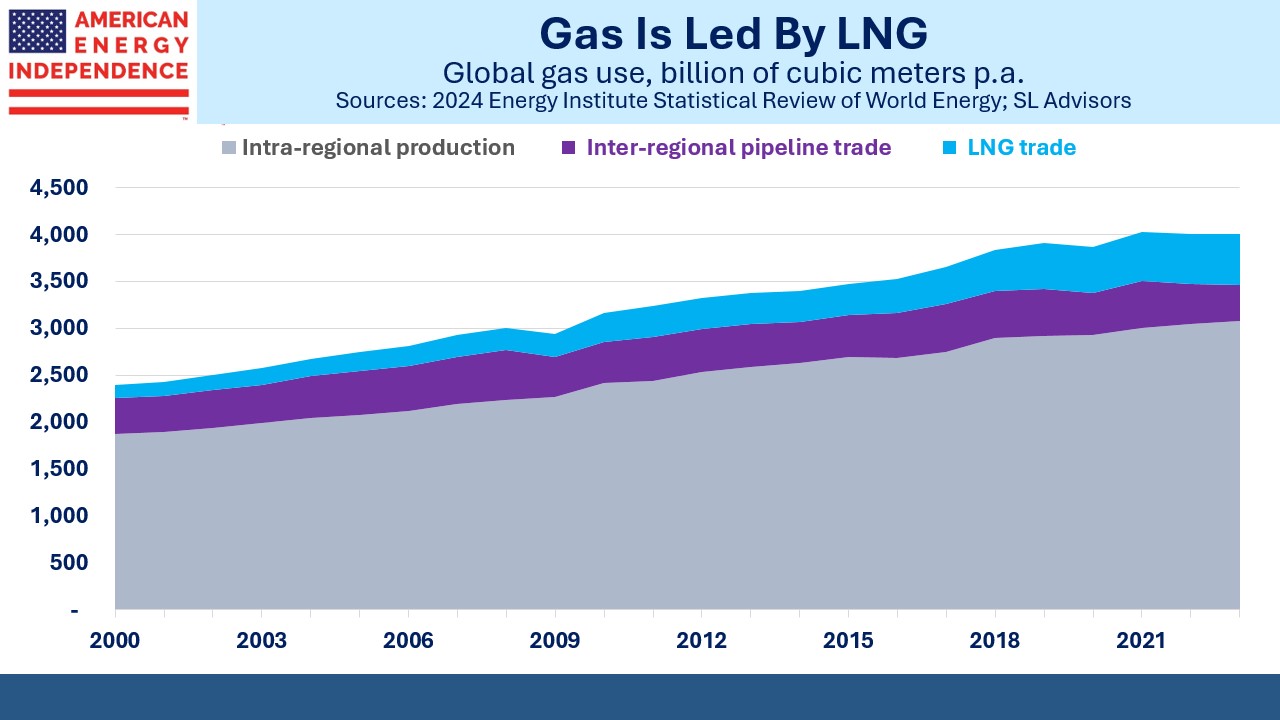

Twenty five years ago the trade in gas via inter-regional pipelines was more than 2.5X as big as LNG. Pipeline volumes peaked just prior to the pandemic when they fell 10%. A brief rebound in 2021 ended with Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. By 2023 pipeline gas volumes were 24% lower than in 2019. The loss of Russian gas exports to the EU was the proximate cause.

By contrast, LNG volumes have climbed steadily, and didn’t even drop in 2020. Energy security became more important following the Russian invasion. A pipeline connecting two countries doesn’t allow any flexibility if relations between the supplier and buyer break down. This was the case with Nordstream before it was mysteriously blown up. China and Russia have been negotiating for years over additional Russian gas supply via the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, with China showing less urgency than Russia to reach an agreement.

Both countries must consider how they’d cope if a dispute caused flows to stop. A Russian adviser suggested that Middle East tensions would spur an agreement so that China could reduce its exposure to the Strait of Hormuz, although this looks like wishful thinking.

LNG trade is around 40% bigger than inter-regional pipeline volumes, and that gap is likely to grow. Moving natural gas by ship allows trade between countries too far apart to be connected via a pipeline. LNG also enhances energy security for both parties, since once the necessary infrastructure is in place, both buyer and seller can negotiate agreements with multiple counterparties.

We often note the projected growth in US LNG export capacity, driven by abundant domestic supply. The Asian JKM benchmark is $13.80 per Million BTUs (MMBTUs), and the European TTF is $13.25 per MMBTU. With US natural gas at around $4, the price differences are easily big enough to make US exports attractive.

Our current LNG exports of around 15 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D) are limited by liquefaction capacity. We expect this to roughly double by 2030 based on projects already under construction.

There are many other projects that have not yet reached Final Investment Decision (FID), so export capacity is likely to continue growing into the next decade.

The US is the world’s biggest LNG exporter with 21% of the market but is not alone in growing. Around half of the “aspirational” capacity as estimated in the International Gas Union’s 2025 World LNG Report is outside North America.

China is 19% of LNG imports, followed by Japan at 16%. Global LNG trade has grown at 6% pa since 2000.

Because there will be more LNG available, some analysts predict this will lead to a global surplus that will depress prices and profitability for exporters. However, receiving capacity is also growing. The facilities that regassify LNG for injection into their distribution networks are more numerous than the liquefaction export terminals. They generally operate at around 40% capacity,

By contrast, global liquefaction facilities operated at 87% of capacity last year. There’s more than 2X as much import capability as export. The world is preparing to use more natural gas, as the unmet promises of renewables mount up. For example, Malaysia just announced a 50% increase in gas-fired electricity to meet rising demand from data centers.

LNG exports will be part of the solution.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: