Interest Rates Are Interesting Again

It must have been a lively FOMC meeting last week. The Fed has obviously committed their biggest mistake in living memory, and they finally started to normalize short term rates. They’re a year late, to the evident frustration of James Bullard who dissented on the 0.25% increase because he preferred 0.50%.

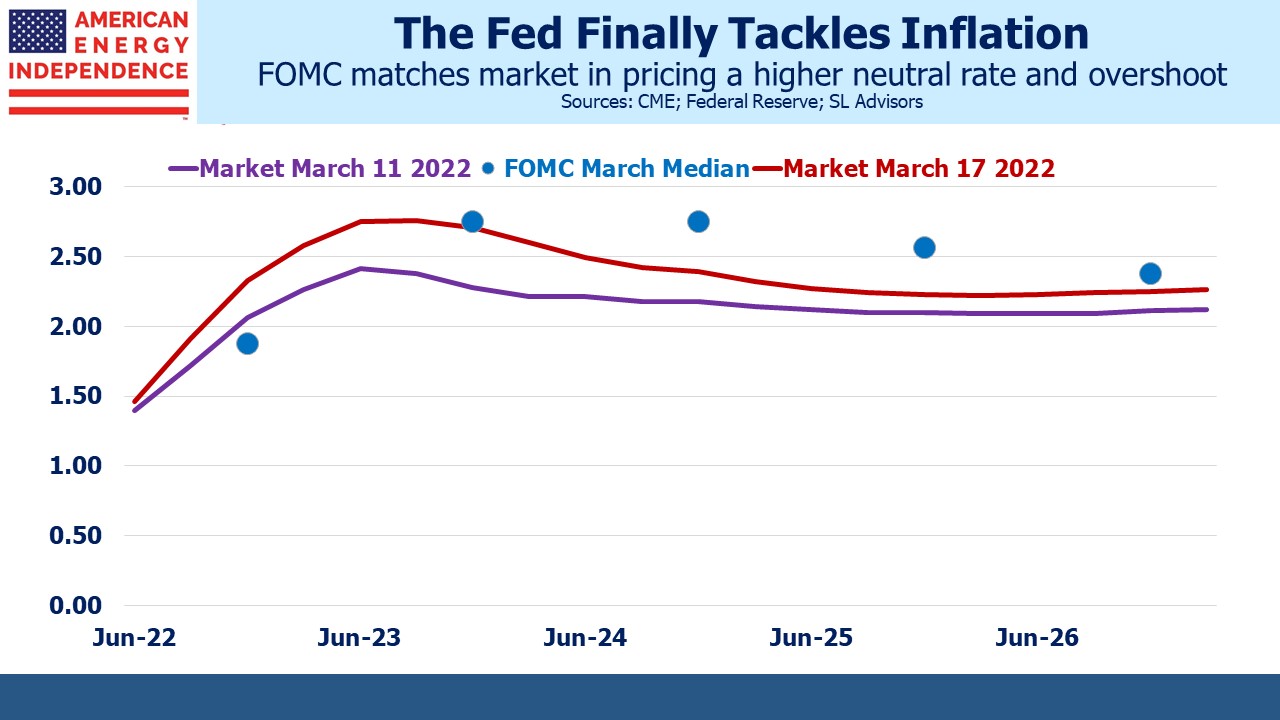

The FOMC revised up their forecasts of short term rates (the “dot plot”) by 1% over the next couple of years. They’re also now projecting they’ll need to raise rates above neutral before reducing them. In this respect they are belatedly confirming the forecast of the eurodollar futures market, although yields overall rose in response to the hawkish tone of the meeting.

Interest rates are interesting once more, after endless years of tedium. In 2008 the CME introduced half-tick increments to create the illusion of greater movement, and even quarter tick on near contracts. But for this blogger who traded interest rates in the 80s and 90s, the last 20+ years have been mostly glacial. Now once more there’s plenty to consider.

Although today’s high inflation is partly due to the Fed misinterpreting deep-seated as transitory, it’s also a consequence of their increased tolerance for elevated inflation in order to maximize employment. Any setback in employment will create a dilemma. Fed chair Jay Powell has argued that stable inflation is necessary to promote maximum employment over the long run. This central bank orthodoxy may sit less comfortably with some FOMC members given their bias towards making sure everyone has a job. Powell is presumably roughly in the middle of his FOMC’s range of views. The Administration is unlikely to add any hawks, especially with a presidential election in 2024.

When the first sign of economic weakness appears, the FOMC will need to assess whether it’s evidence that tighter policy is already doing its job. In recent tightening cycles the economy has succumbed at successively lower peaks. Somewhere on the way from 1% to 2% some self-doubt may intrude.

The matter is further complicated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is disingenuous for Biden to refer to “Putin’s gas hikes” since the global supply of oil and gas were already impeded by greatly reduced capex. The independent voter likely understands that promises to phase out fossil fuels, along with canceling the Keystone XL pipeline, were hardly intended to encourage more output.

Rising prices for wheat, corn and numerous other commodities exported by Russia and Ukraine can be more properly traced to Putin, but those haven’t yet captured consumers’ attention. It’s a boon for US farmers, although don’t expect to hear any suggestion of a windfall profits tax on agriculture.

The Fed’s next challenge will be to interpret which elements of inflation they should care about. Traditionally they’ve worried most about wage inflation. Higher commodity prices represent a wealth transfer and, to the extent that wealth flows outside of the US, a drag on GDP. Pre-Ukraine, higher oil was caused by Covid recovery, the $1.9TN American Recovery Act of early 2021 and energy sector financial discipline. The first two warranted a monetary response. The more recent and broad based jump in commodity prices is down to Russia and the west’s reaction. This is contractionary, in some respects achieving the same goal as higher short term rates.

The path of sequential tightening described by Powell and reflected in the yield curve is vulnerable to being shaken by signs of weakness. Some FOMC members, smarting from the previous error, will be inclined to press on. Strong advocates of favoring maximum employment over inflation will want to pause. The yield curve will shift.

The range of FOMC rate forecasts widened at last week’s meeting compared with December. This is especially evident over the next couple of years. The range of forecasts for the end of this year has widened to 2% from 1%, and for 2023 to 1.5% from 1%. Just as forecasting next month’s return on stocks is harder than next decade’s, so it is with interest rates. The most dovish 2023 forecast is 2.25%, equal to where the three hawks were in December.

This suggests a wide range of views, and therefore uncertainty on what the correct rate path should be.

For investors, it makes interest rate volatility more likely as FOMC members navigate an especially difficult environment. It means the inversion in the yield curve 2023-24 could vanish if economic weakness leads to even a slightly slower pace of tightening. And it means inflation is unlikely to return to 2% for years.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.