Inflation Edging Higher

Yesterday the IMF warned central banks around the world to be “very, very vigilant” about inflation. The Fed and its peers employ legions of economists and it’s doubtful the IMF will have triggered a sudden reassessment in marble halls in Washington, Frankfurt or Tokyo. But their outlook will add to the growing concern investors have about inflation and the likelihood of it remaining elevated.

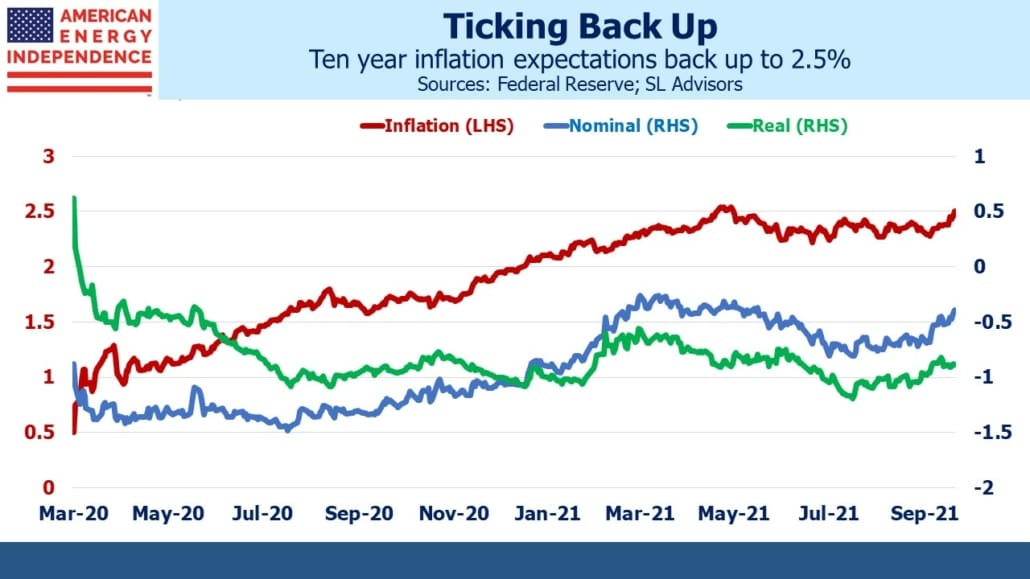

Inflation expectations as derived from the treasury market have edged up in recent days – the ten year forecast average inflation rate as derived from the bond market (ten year treasury yield minus ten year TIPs) is now 2.50%, close to the high it reached in May of 2.54%. The NY Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations also reflects rising inflation fears among consumers. Three years out the median is now above 4%. Although the IMF, like most forecasters, expects inflation to come back down, they revised up their forecasts sharply. Compared with April, they now expect developed country inflation to be 2.8% this year (versus 1.6% in their April forecast) and 2.3% next year (versus 1.7%). Like the Fed, the IMF was way off for 2021 inflation.

Real rates (i.e. the return investors need after inflation) are solidly negative, having reached –1.0% in August before improving recently. The persistent fall in real yields is an important reason why interest rates are so low. Explanations include increasing income inequality (rich people save more) and a growing pool of return-insensitive investors such as central banks who own treasuries for safety and liquidity. Whatever the reasons, the drop in real yields has continued even while the fiscal outlook for the US and others has dimmed. The warnings of deficit hawks look old fashioned.

In Bonds Are Not Forever: The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors (2013) I argued that an increasingly indebted society would favor low real returns and tolerate higher inflation, since these are the least painful way to repay less than was borrowed, in real terms. These themes have continued today, accelerated by the Covid-inspired uber-stimulus.

A recent op-ed in Bloomberg made the case that higher inflation (say, 4%) would benefit the US. The writer argues that it would make debt more manageable, and would provide the Fed more room to lower rates in a recession. It’s easy to see how this view could gain support. Record Debt:GDP challenges the orthodox view of fiscal hawks by not presenting any real economic problems. Modestly higher inflation could be the same.

Maintaining income growth at reported inflation is likely to leave one feeling poorer (see Why It’s No Longer Enough To Beat Inflation). House prices are the biggest omission from inflation indices, but quality adjustments also create a result that doesn’t capture changing living standards. When a new iphone is released at the same price as the older version, its new features mean it goes into inflation statistics as having dropped in price. But you can’t buy 95% of an iphone, so there’s no actual saving.

Hedonic quality adjustments are intended to strip out the improvements that constitute rising standards of living, since inflation statistics aim to measure “constant utility.” This is hard to do in practice, especially with services. A recent article noted that the CPI omits “quality adjustments on 237 out of 273 components that go into the index, including the vast majority of services.”

To give one example, on a recent road trip from Charlotte, NC to Naples, FL we noticed that hotels don’t automatically provide daily room make-up service for guests. It needs to be requested, and since some guests don’t bother, the hotel is saving some money. Having to specify the type of service (one hotel offered “full or partial”) each morning is a small drop in quality almost certainly overlooked by the price indices. Quality improvements for services are more subjective – the same article noted longer wait times for service at high-end retail outlets – another reflection of the shortage of workers. Inflation statistics are relevant in that they determine Fed policy and cost of living adjustments for retirees, but they’re so deeply flawed that their use is limited beond that.

The IMF is forecasting US GDP growth of 5.2% next year – substantially more than the Fed’s forecast last month of 3.8% (revised up from 3.3% in June). Although Friday’s non-farm payroll report was a disappointing 194,000, the unemployment rate fell 0.4% to 4.8%. Hourly earnings continued their series of increases, rising 0.6% although the Bureau of Labor Statistics cautioned that large fluctuations in employment across industries since Covid struck complicate the analysis of whether or not wage inflation is setting in.

Fed policymakers normally eschew anecdotal evidence, but the evidence of a booming economy is overwhelming. Help wanted signs are abundant. Worker shortages are being reported across many industries. The housing market remains buoyant, and the FOMC’s ponderous roll-back of bond market support will likely turn out to have been recklessly delayed.

Finally, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman sounded so intelligent on this recent video that he’s jeopardizing his liberal credentials. He blamed the global energy crisis on insufficient investment in natural gas and too hasty an exit from nuclear power (Germany and California) without first establishing reliable alternatives. His policy prescriptions echoed those often found in this blog – the hope for more pragmatic solutions to CO2 emissions may not be in vain.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: