Inflation Concerns Remain

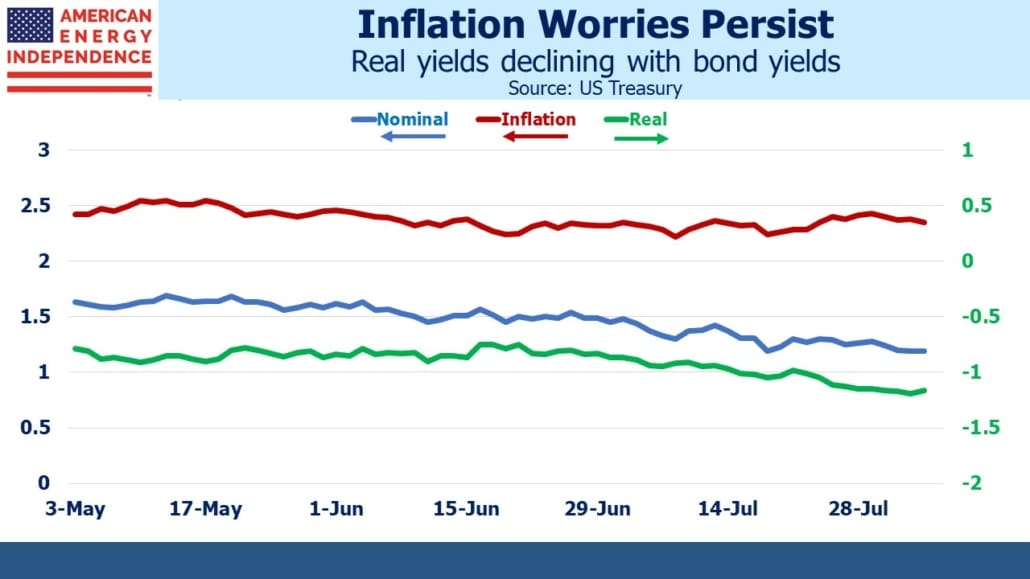

The fall in treasury yields can be misinterpreted as implying that inflation expectations are moderating. Although ten-year treasury yields have dropped 0.40% over the past three months, almost all of that has been through lower TIPs yields. Inflation expectations (nominal yields minus TIPs) have hardly budged.

Given the Fed’s outsized role in the bond market, it’s hard to discern market expectations absent their activity. They’re buying 54% of all net supply this year, and as we noted a couple of weeks ago (see Behind The Fed’s Benign Inflation Outlook) they bought 85% of net new supply in July. Over the next couple of months, reduced maturities and increased issuance combined with the Fed’s regular $80BN in monthly purchases will draw on increased purchases by others to balance the market.

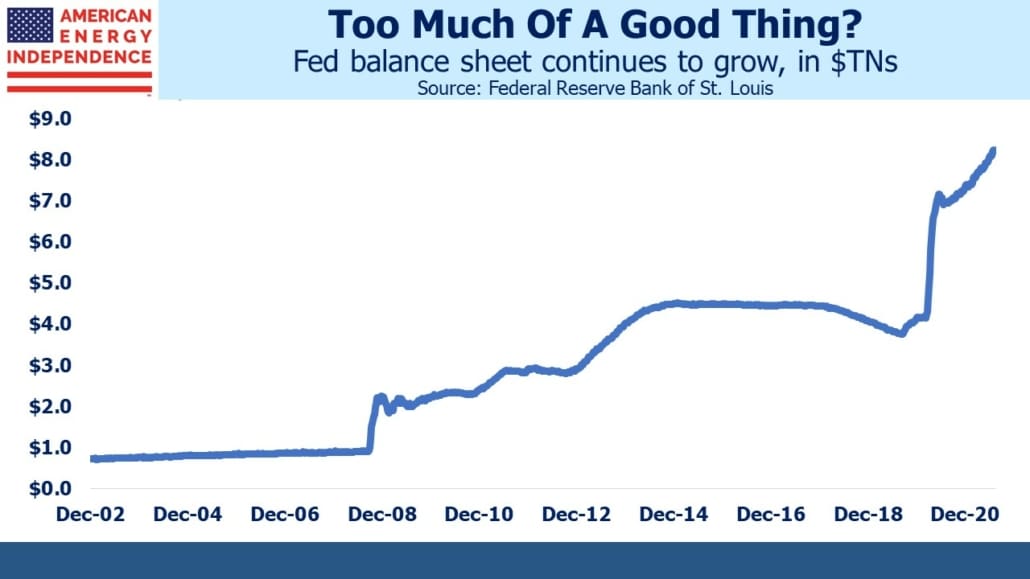

Friday’s payroll report kept us on the interminable path towards tapering and an eventual cessation of Fed debt monetization. Former NY Fed president Bill Dudley was interviewed on Bloomberg and noted that restoring the Fed’s $8TN balance sheet to more normal levels will take many years.

Prior to 2008, quantitative easing via Fed buying of bonds was an unknown tool. Former Fed chair Ben Bernanke unlocked it to good effect, but the Fed’s balance sheet continued to grow for several years after the 2008-09 financial crisis. It took almost a decade for assets to start rolling off meaningfully. Covid hit within a year, and the Fed’s assets soon doubled.

It is a partial monetization of our debt, no matter how Fed chair Powell may describe it otherwise. Society’s tolerance for this is one more proof that inflation has few opponents nowadays. Monetary policy aims, “to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time” according to the FOMC’s most recent statement, and the bond buying will continue until, “substantial further progress has been made toward its maximum employment and price stability goals.”

While the Fed aims to boost inflation, fiscal policy is striving for the same. The $1TN infrastructure plan working its way through Congress will add $256BN to the deficit according to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, even though negotiators claimed that it would be revenue neutral.

Expect very little outcry over this, since low bond yields reflect the inconsequential cost. With fiscal hawks long gone, excessive deficit spending will continue until it causes inflation. The stock market’s brief pullback in mid-July was arrested in part because of the “Biden put” — a severe drop in economic activity would draw another multi-$TN fiscal stimulus.

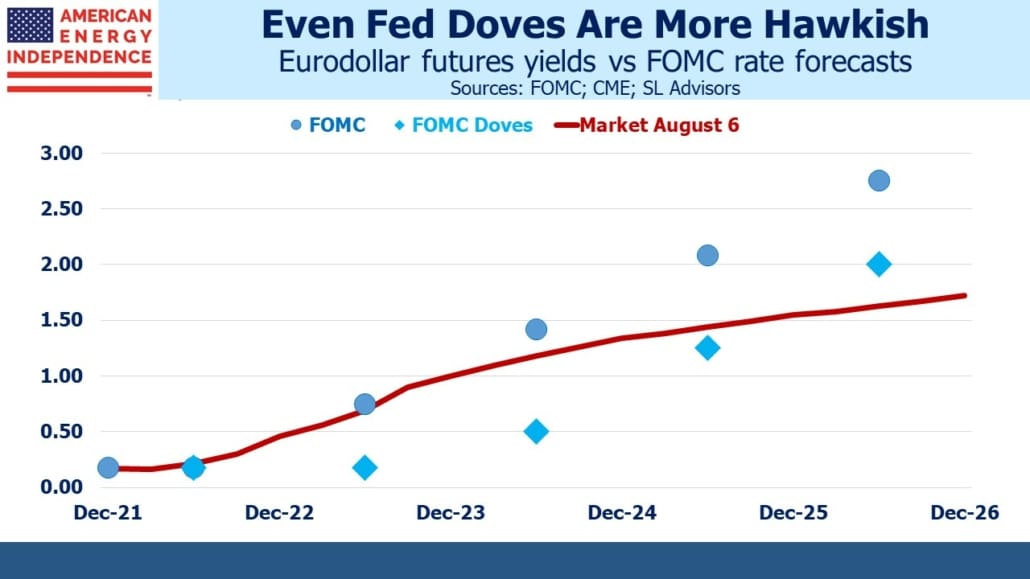

Although bond yields have remained near their recent lows, eurodollar futures yields rose during the week as the odds of a tightening in short term rates by the end of next year increased.

The yield curve nonetheless remains too flat. Median FOMC projections of short-term rates as well as the most dovish forecasts both suggest a sharper rate of increase from 2023 on. The FOMC’s forecasting record is abjectly poor. But this Fed is unashamedly dovish, so FOMC forecasts that are more aggressive than the market continue to look like an opportunity to bet with the FOMC by positioning for a steeper yield curve in eurodollars 2023-25, or that the 0.55% spread between two and five year treasuries is too narrow.

In other news, the Economist magazine recently ran a piece called A 3°C world has no safe place. It presented a sober contrast between the (mostly unmet) pledges of countries to reduce CO2 emissions and the scientific modeling that predicts the consequences. Rich countries committed $100BN per year to help developing countries adapt, although even this sum has not been delivered. Even though such promised transfer payments get virtually no coverage in US media, political leaders in countries like South Africa can be found on TV telling viewers that much larger sums are needed to pay for the energy transition.

As we noted in a recent podcast (Episode 79: The Bill For The Energy Transition), South Africa believes $750BN per year is needed from OECD to emerging economies, which would work out to $250BN from the US if apportioned among rich countries based on relative GDP. This is almost 4X what we spend on Medicare and Health, or over 40% of our defense budget. It’s as well that such discussion doesn’t make it to the US, because it would at a minimum cast a pall over the Adminstration’s excited talk about green growth opportunities.

One of the most striking features of the Economist article was how slowly the climate changes. Models, which have a checkered past of making climate predictions although presumably are better today than ever, forecast dire consequences by 2100. None of the people likely to be impacted by this can read the article, while the people who must make sacrifices in the meantime to reduce emissions will have mostly died by then.

It’s why developing countries like China and India are more concerned about increased energy use to raise living standards now, and don’t share the concern of OECD countries about global warming.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.