How Tightening Impacts Our Fiscal Outlook

For anyone in finance, the US budget deficit has always been a looming disaster but rarely a current problem. It hasn’t been a political issue since Clinton ran for office and Jim Carville quipped that the bond market intimidated everybody. For a few brief years we had a budget surplus (1998-2001), but fiscal prudence long ago lost its appeal with voters because the current costs of profligacy are inadequate to impact elections.

But tomorrow is approaching, and according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) sooner than we thought a year ago.

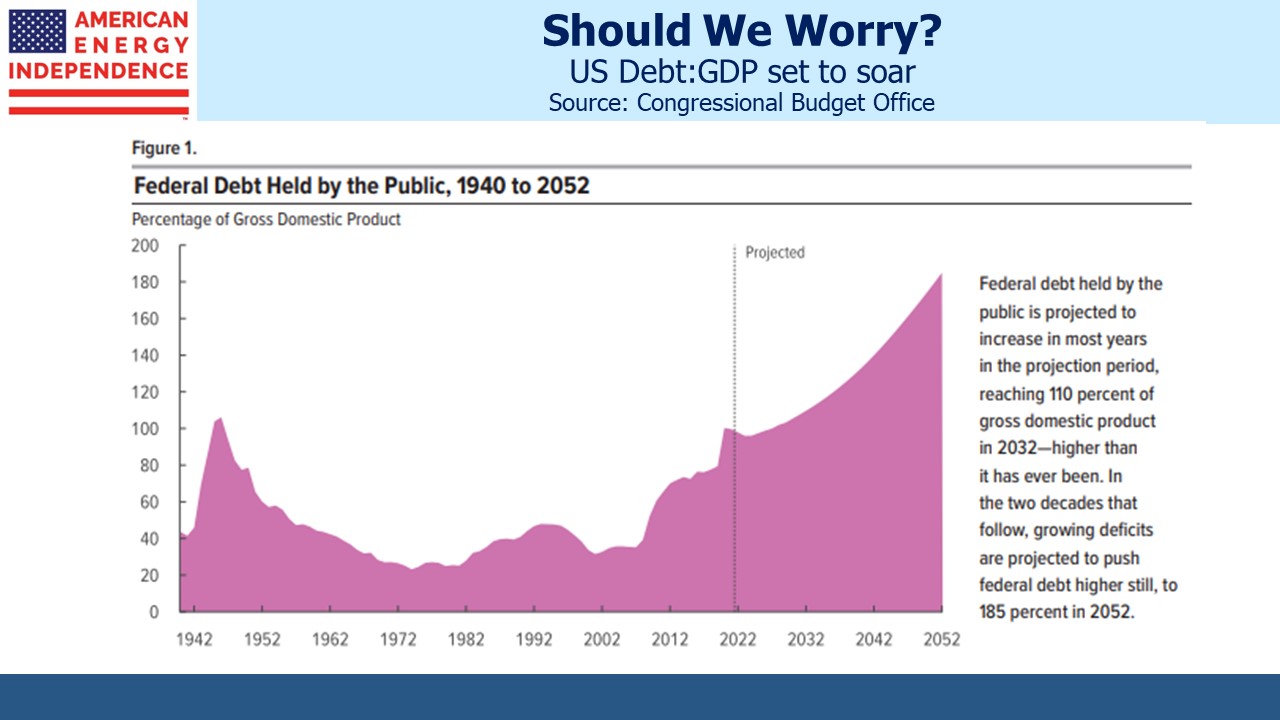

Last week the CBO updated their 10-year budget projections, with disappointing revisions compared with the prior release last May. Our Debt:GDP is at levels last seen towards the end of World War II. Back then following the end of hostilities spending fell, and artificially depressed government bond yields helped lower the country’s debt burden.

This time around, ballooning Medicare and social security spending will take us into uncharted territory.

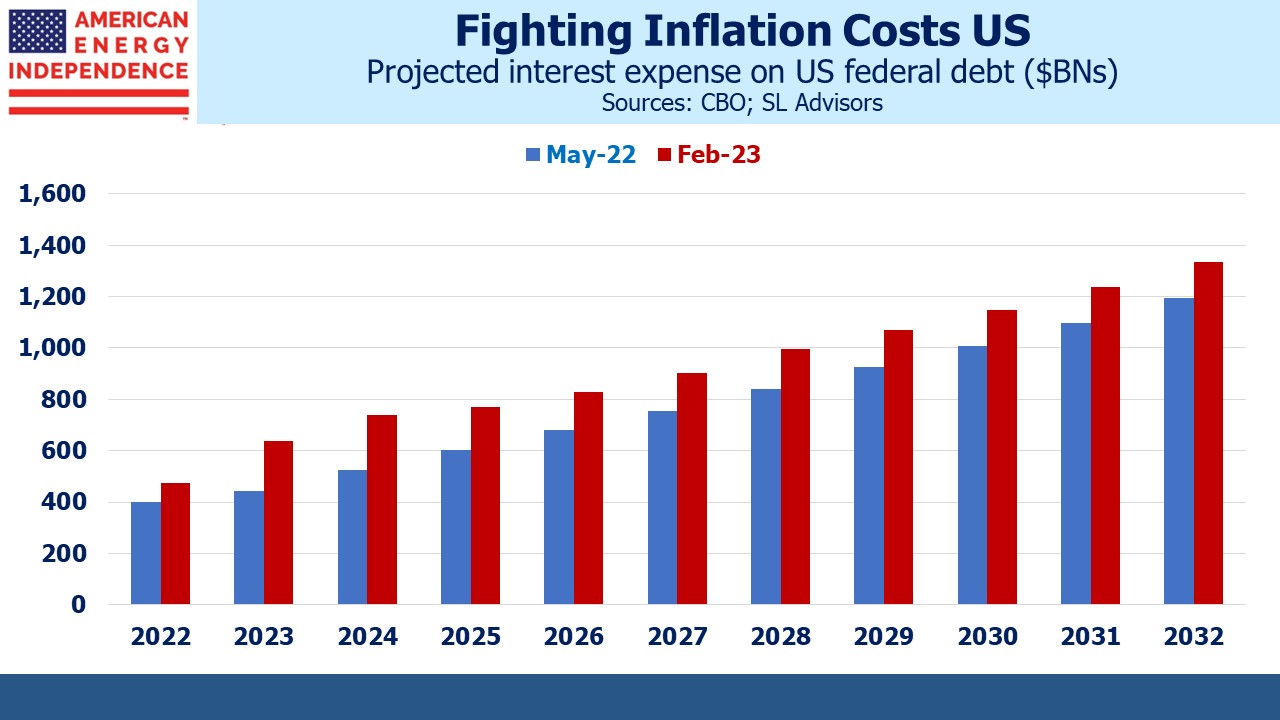

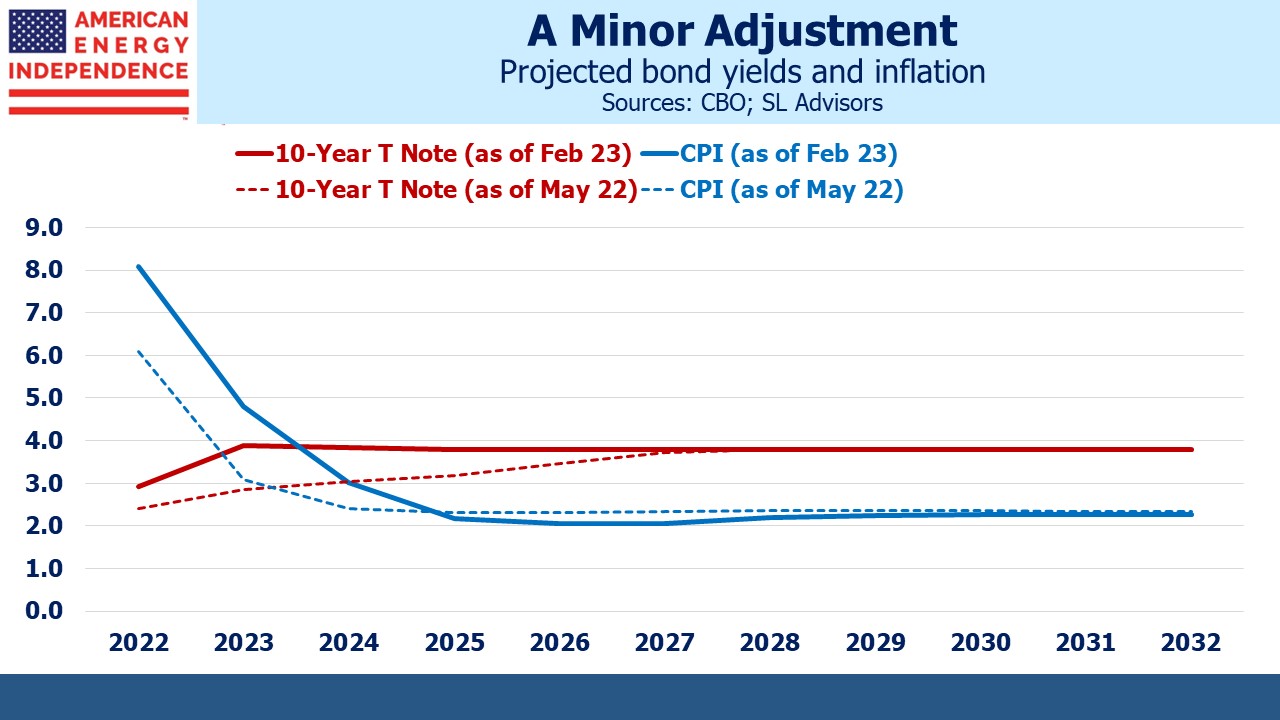

Rising debt has increased our interest rate sensitivity. The CBO’s outlook for inflation and bond yields hasn’t shifted apart from reflecting today’s higher inflation. Compared with last year’s forecast, inflation is expected to return to the Fed’s 2% target a year later.

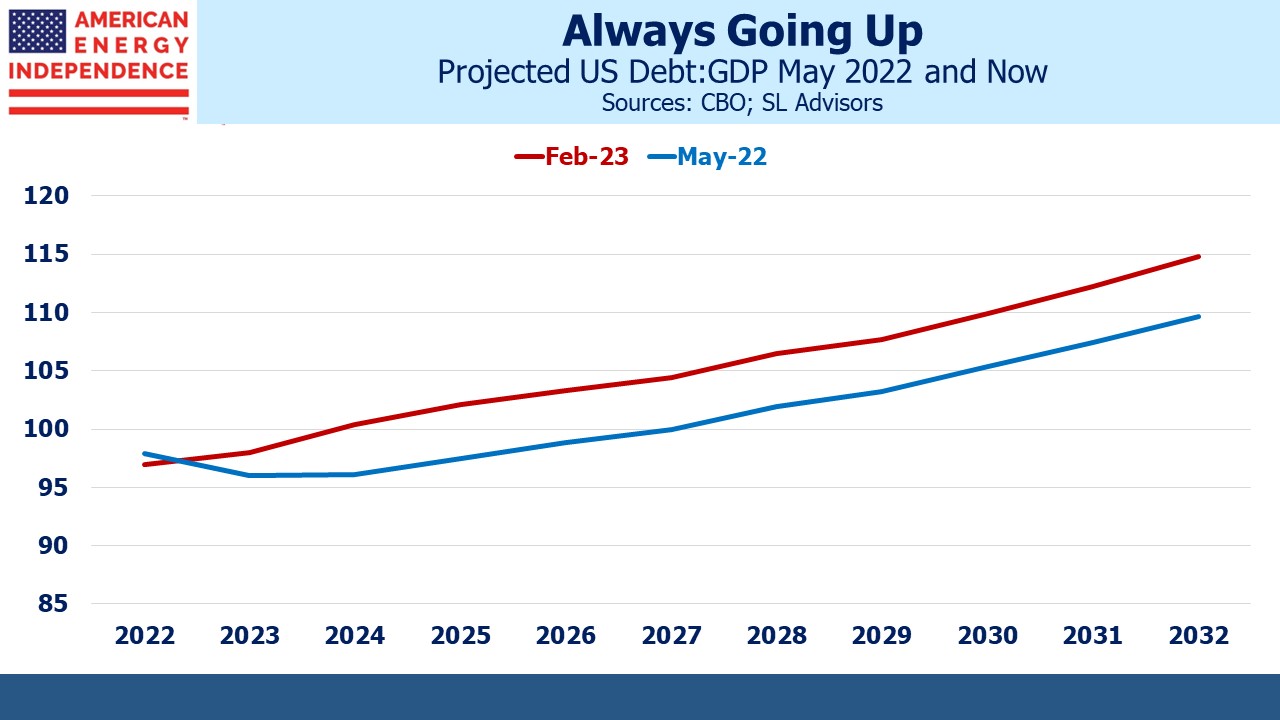

The impact on our finances has been dramatic. Debt will now exceed GDP next year, four years earlier than before. Interest expense over the next decade will be $159BN higher annually, bringing forward by approximately two years milestones such as $500BN, $1TN or $1.25TN in annual debt servicing cost.

The White House is unlikely to dwell on this, but the change in circumstances between the two CBO publications might represent the most rapid deterioration in America’s finances in history. The bigger the problem gets the harder it is to solve.

It would be worse without Quantitative Easing (QE). The Fed still holds $5.4TN in government bonds and another $2.6TN in MBS. Without return-insensitive buyers such as central banks (see More Than A Fiscal Agent) and others with inflexible investment mandates financing our debt would be even more costly.

The Fed follows its dual mandate by focusing on whichever of the two variables (employment or inflation) is farthest from its desired level. In the summer of 2019 at Jackson Hole, they concluded that we could tolerate a little more inflation over short periods to boost employment (see The Fed’s Balance Sheet Has One Way To Go). The timing was unfortunate, and within a couple of years a modest overshoot demanded their attention.

The Fed’s Congressional mandate doesn’t include concern about the fiscal impact of their actions, but they are becoming more impactful. QE has emasculated debt hawks by hiding the apparent cost of fiscal excess. QE’s slothful removal has impeded the Fed’s efforts to slow the economy, as seen in recent strong data such as employment and retail sales.

The current tightening cycle hasn’t been enough to raise unemployment, but it’s had a meaningful impact on our debt outlook. The Fed’s interpretation of its dual mandate now has a fiscal dimension.

The logical response is to tolerate higher inflation. There’s nothing magic about 2% – stability is more important than its level (see El-Erian, Rogoff Say It’s Too Late to Fix Too-Low Inflation Target). The numbers suggest that tolerance of 3% inflation leaves us better able to service our debt than 2%. There are few tangible benefits from the current effort to stick to the old inflation target.

Last year interest expense alone was 1.90% of GDP. Within a decade it is expected to reach 3.52%, up from a 3.254% projection in May.

The Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections has the Fed Funds rate ending this year at 5.1% and next year at 4.1%. The CBO expects Fed Funds to average 3.6% in 2024 (last year they were projecting 2.6% for 2024). If the Fed is right, the CBO’s 2024 interest rate forecast will be around 1% too low, which will result in further adverse updates to our fiscal outlook.

The CBO aligns with where interest rate futures were when they prepared their budget outlook. Since then, strong data has caused the market to shift towards the Fed’s projections.

Fed chair Powell has been clear that bringing inflation back to 2% is in everyone’s interests. While this is consistent with their Congressional mandate, it’s no longer the most desirable public policy. Our vast debt, poor fiscal outlook and heightened interest rate sensitivity make increased inflation tolerance preferable.

For now, investors should take the Fed at its word that they’ll do what it takes. But the impact on our finances of returning inflation to its 2% target is eventually going to make this a consideration. It means defining price stability as 2% inflation is becoming more costly. Maintaining the purchasing power of your assets means assuming inflation settles in higher than this target.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: