Get Your Foreign Exposure In America

Investors are routinely advised to incorporate some international exposure into their portfolios. This can be to add diversification or, in the case of emerging markets, to participate in faster-growing economies. For a US-based investor, this is at best a waste of time. Worse, it can introduce unneeded complexity, cost and poor returns.

By investing in countries that are developing quickly, the hope is that faster growth in GDP and incomes will translate into higher equity returns. This approach has provided years of disappointing results. It’s been good for investment managers who charge high fees to provide specialized access to such markets, but not for their clients.

The first mistake is to confuse GDP growth with equity returns. Take those famous empty, unfinished apartment buildings across China. Their construction generated economic activity and boosted GDP, but they’re not generating returns for the capital that financed them. Capex that fails to generate a return above its cost destroys equity value and isn’t limited to profit-seeking enterprises. Governments are equally capable of poor investment choices.

In fact, for many countries the transmission mechanism linking GDP growth and equity market returns is weak. There is ample literature on this point, such as Triumph of the Optimists (2001) which examined a century’s worth of data. The analysis was updated in 2021 with similar conclusions. An academic paper from 2022 (What Matters More for Emerging Markets Investors: Economic Growth or EPS Growth?) provided confirmation.

Moreover, direct investing in foreign markets incurs risk to foreign concepts of property rights, disclosure, accounting standards and fair markets. Many countries aspire to American standards, but few achieve them. I remember visiting India years ago to meet with local hedge fund managers and being told by a regulator that there was no insider trading in their markets. In such cases the only plausible approach is to invest with inside information or not at all. We never invested in Inda.

Then there’s the quandary of which foreign markets to choose and what allocation to make. Done properly, this requires substantial research of relative valuations, investor protections and economic prospects. This level of analysis is way beyond all but the most sophisticated institutional investors.

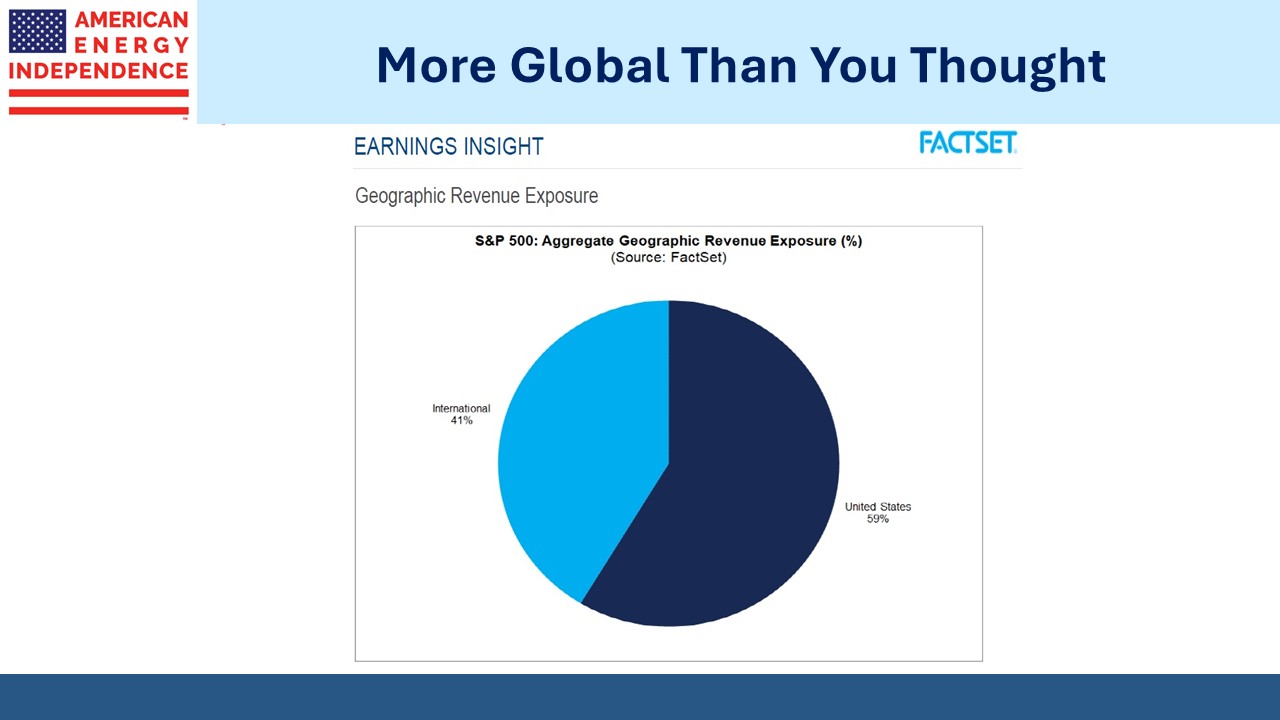

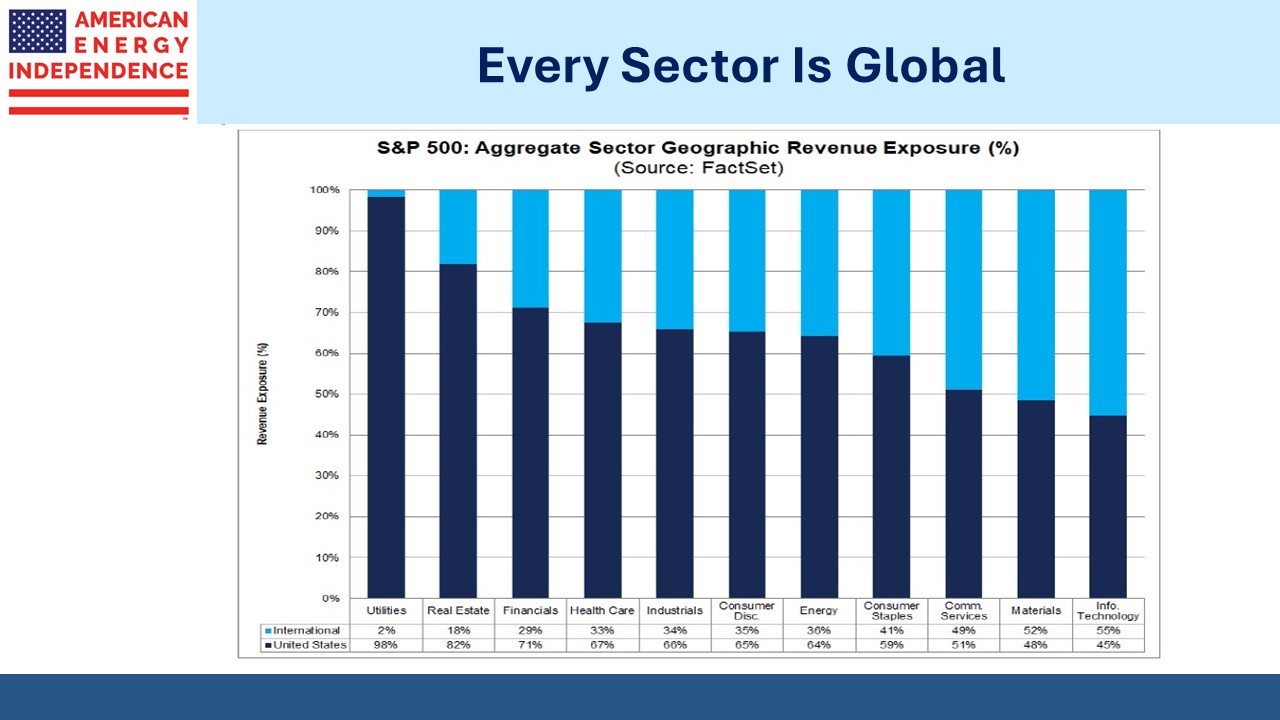

The S&P500 contains most of the world’s biggest companies. Almost all of them do business overseas. Investors are often surprised at the portion of revenues these 500 companies generate outside the US, which Factset calculates at 41%. It’s not just the Technology sector either – all eleven sectors have some exposure outside the US, although not surprisingly it’s low for Utilities and Real Estate. But the figures should provide comfort to any S&P500 investor who fears his holdings are too parochial.

What’s the right allocation? 500 boards of directors and executive teams have considered the opportunities from Argentina to Morocco to Vietnam and have invested accordingly. Their blended exposure to different countries represents the aggregate best thinking of this group. It’s crowdsourcing – the result of so many independent opinions is likely to be better than the informed view of an individual investor.

In addition, these companies have navigated through local regulations, taxes, property rights, accounting standards and politics in making those choices. Put another way, if the American Widget Company listed on the NYSE decides to create a subsidiary in Brazil, you’re better off getting your exposure through them than trying to identify a Brazilian widget company listed in Sao Paulo.

Instead of trying to identify Indian companies that will give you exposure to that country’s growing middle class, why not let Apple do it for you.

The Wall Street Journal recently advised its readers to allocate around a third of their portfolios internationally. Ironically this is less foreign exposure than the S&P500 currently provides. An investor who followed this advice would wind up with more than half their exposure outside the US, an imprudent choice for someone living in America.

The WSJ article ignored the abovementioned research and instead noted that, “Overseas equities are beating domestic shares for one of the few times in 15 years…” Most of the market advice from the media is on trading. Investors don’t hop into a sector on the basis of a few good months. So much energy is spent on timing rather than strategy.

The S&P500 offers ample diversification and a more efficient, safer way to access investment opportunities beyond our borders. Shun the advice of the poorly informed adviser who wants to make your portfolio more complicated and therefore renders his advice harder to evaluate.

Simpler can be better.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: