Falling Dominoes

“Rusty” Braziel runs RBN Energy, a firm that provides very useful research on production trends in U.S. hydrocarbons. Their website maintains a regular blog and also offers deeper analysis on specific topics. They reach over 20,000 industry executives, and we find many useful insights in their work.

The Domino Effect: How the Shale Revolution is Transforming Energy Markets, Industries and Economics was published early last year, coincidentally just a few weeks prior to the low in the energy sector’s bear market that was largely due to U.S. hydrocarbon output. Like his blog posts, Rusty’s book is well researched and highly engaging. He describes events as dominoes falling against one another in a seemingly inevitable sequence. The first domino was caused by improvements in technology that drove significantly enhanced returns from shale-sourced natural gas production. The consequent abundance drove the price of natural gas lower, inducing Exploration and Production (E&P) companies to switch to more profitable Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs), which were often found with or nearby “dry” natural gas. Lower prices followed for NGLs, and activity then shifted to crude oil. The resulting increase in U.S. production drew the world’s attention to the Shale Revolution as crude slumped in 2014-15.

The dominoes continued, creating a resurgence in U.S. petrochemical investments funded by cheap inputs such as ethane, an NGL. Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) import facilities were converted to export, since U.S. natural gas prices fell to among the lowest in the world. The book’s explanation of events as inevitably linked provides a compelling framework with which to examine huge shifts in world energy markets.

There is some interesting history; in 1942 the success of German U-boats at sinking oil tankers traveling from the Gulf Coast to New York harbor prompted the rapid construction of pipelines from Texas up to Philadelphia and New York. One of those pipelines, dubbed “Big Inch” because of its 24 inch diameter (double the diameter of the largest to date), was converted from a crude line after the war to carry natural gas. Today it is the TETCO pipeline operated by Enbridge (ENB). Another, smaller pipeline from the same era named Little Big Inch carried refined products. It’s now the Products Pipeline System (formerly known as TEPPCO) and is run by Enterprise Products Partners (EPD). These represent compelling examples of the longevity of pipelines, showing that properly maintained infrastructure that’s still in demand can steadily appreciate in spite of GAAP accounting that allows for depreciation.

Pipeline operators handle the differing quality of crude oil and mixed NGLs from their many customers by operating a “quality bank”. This values the difference between what a specific customer puts into the pipeline versus the “common stream” of mixed products, creating offsetting debits and credits that allow more efficient utilization. Because natural gas pipelines typically require a fairly pure input with limited impurities, these operate differently. The homogeneity of natural gas makes it fungible, allowing a shipper to put produced gas into a network and receive immediate credit for it at the other end without waiting for the actual molecules to travel the distance.

A handy comparison of the different volumes of natural gas and crude oil consumed in America every day calculates how many times they would fill the Empire State Building. Natural gas (in the gaseous state in which it’s typically moved) would fill that space 1,917 times, compared with only 2.4 times for crude. We often write that energy infrastructure is primarily a natural gas business.

We have written about the Rockies Express (REX) gas pipeline now owned by Tallgrass Energy Partners (TEP; see Tallgrass Energy is the Right Kind of MLP). The Domino Effect recounts the original construction of REX by Kinder Morgan (KMI), completed in 2009, as it moved natural gas from the Rocky Mountains to the gas-starved (as it was then) northeastern U.S. One of many consequences of the Shale Revolution has been TEP’s successful reversal of REX to supply Midwestern customers with natural gas from Pennsylvania and Ohio. Pipelines typically resolve regional price differentials caused by relative abundance and scarcity. Prior to REX, Rockies natural gas languished as low as $0.05 per thousand cubic feet (MCF) before leaping to $9 in 2009 when connected to other markets.

Coming after the book’s publication but consistent with the domino theme, OPEC conceded the inevitability of continued U.S. crude production late last year when they agreed on production cuts (see OPEC Blinks). Recent developments appear increasingly inevitable as presented by Rusty, and he provides a solid foundation for those who believe that the cheap, secure resources unlocked by American know-how are unambiguously good.

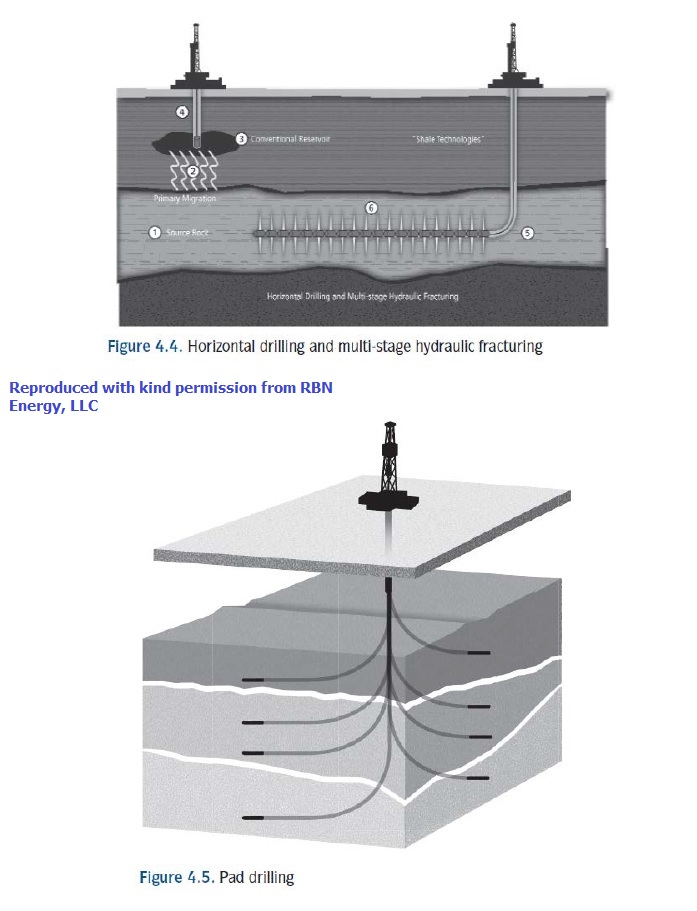

This interpretation of recent history combines easily with very useful explanations of how hydrocarbons are extracted, moved and refined. Readers get the macro analysis along with an understanding of the basics of drilling. One helpful picture (see above) reveals the main difference between a conventional well and a shale one. Hydrocarbons originate in porous rock, and have historically been extracted where they migrate underground to an open subterranean cavity where a vertical drill can reach them. The Shale Revolution taps directly into the original porous rock, allowing access to reserves that were previously known but inaccessible. Moreover, certain formations such as the Permian consist of multiple layers, allowing pad drilling with multiple wells which has led to dramatic improvements in efficiency.

The final three chapters look ahead to the geopolitical implications of the Shale Revolution. America is the clear winner. The most obvious losers are the members of OPEC, whose oil revenues are destined to be substantially lower even while they also cede market share through reduced exports to North America. It’s quite possible that the U.S. will be less engaged in the Middle East as our energy reliance subsides, a development that most Americans will cheer.

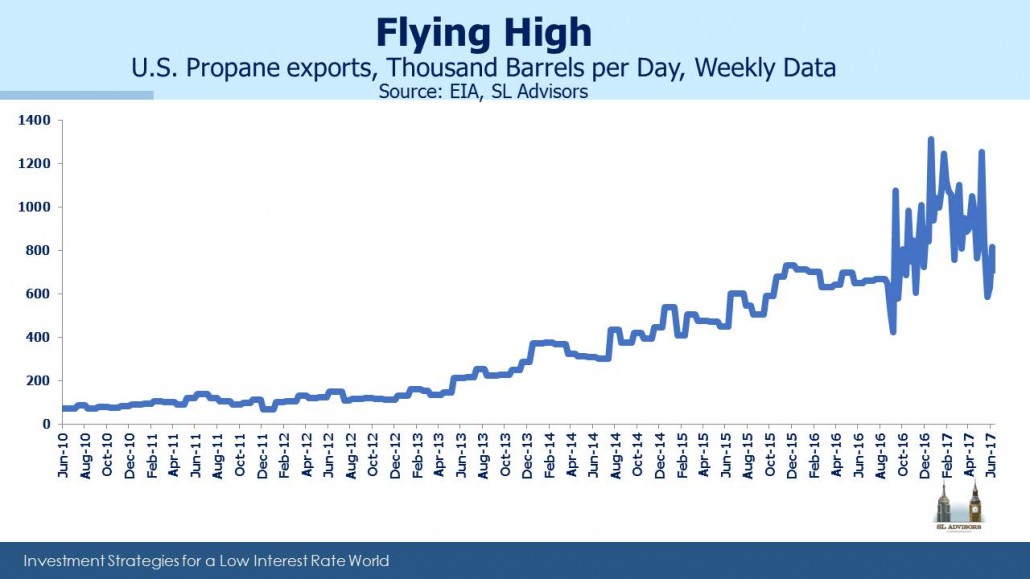

Europe stands to benefit from U.S. LNG exports which will reduce reliance on Russia, where pipeline maintenance is synchronized with political objectives. But the U.S. petrochemical industry is likely to benefit at Europe’s expense from cheap, local NGL feedstocks. The decline in European oil production will probably accelerate. Crude oil and natural gas get the headlines, but NGLs are an under-appreciated success story too. For example, exports of propane (what fuels your barbecue) have jumped well over tenfold since 2010.

Russia will increasingly find the U.S. is a competitor in energy markets, exposing that country’s relatively undiversified economy (60% of Russian exports are oil and gas).

A minor quibble is Rusty’s assertion that America invented representative democracy (“another global revolution”) around 240 years ago. This overlooks the Greek origin of the word as well as that history didn’t start in 1776. But we’ll forgive the Texan hyperbole because there’s so much else in the book that’s worth reading for anybody interested in the Shale Revolution.

We are invested in ENB, EPD and Tallgrass Energy GP (TEGP, the GP of TEP)