Emerging Markets Never Do

Allocating to emerging markets is a Wall Street construct designed to confuse investors and justify periodic reallocations to higher fee products that obscure measures of relative performance. Some financial advisors will be outraged at this statement. So let me quickly move to the evidence.

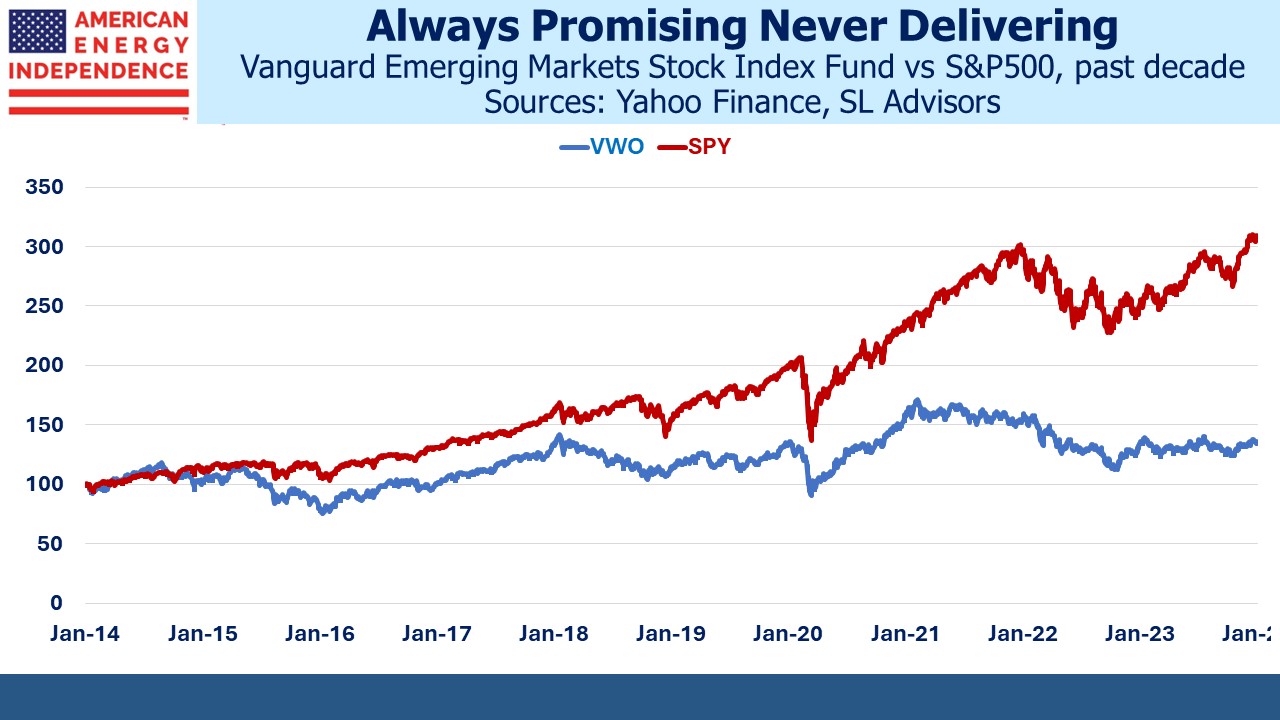

Start with the Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index Fund, the biggest ETF in the sector. Over the past decade it has returned 3% pa versus the S&P500’s 12%. Emerging Markets (EM) hasn’t just had a poor couple of years. It’s had a lousy decade.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Nobody ever emerges from an EM index. For my entire 44 year career in finance, the EM composition has barely changed. “Emerging” is a marketing gimmick that suggests upward progress. But in reality, these countries are all destined to have living standards below the OECD (ie developed countries) indefinitely.

Nobody ever emerges.

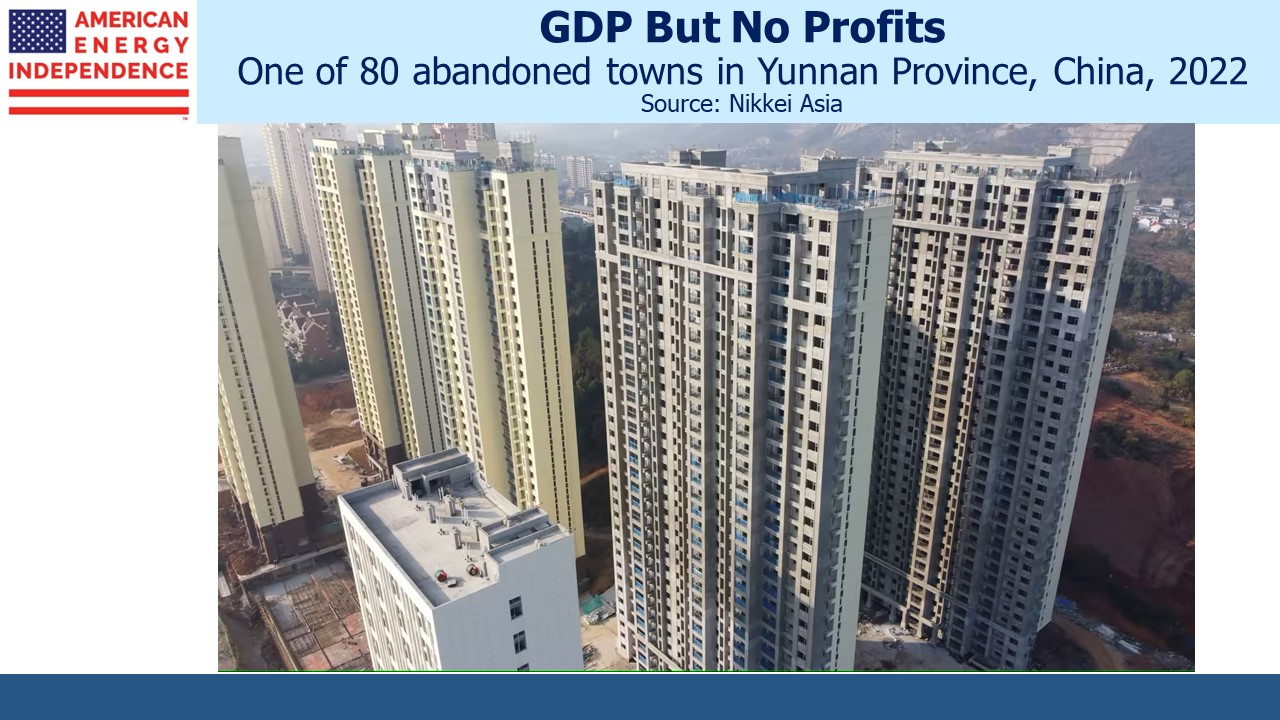

EM proponents will argue that their higher GDP growth means better equity returns. But GDP and corporate profits are different. An uncompleted apartment building generates GDP but is clearly not generating any profits to equity owners if its units can’t be rented. China’s many zombie cities are an example. Building out infrastructure creates immediate GDP, but only helps equity investors if it improves an economy’s productivity.

Many countries exhibit a poor transmission mechanism from GDP growth to equity returns.

Then there’s disclosure standards and property rights. EM countries typically don’t meet western standards on these two issues. The EM investor adopting the tenuous argument that GDP growth = corporate profits next has to consider that the companies she’s invested in are less than transparent in their accounting. Or that local government officials may misappropriate parts of the businesses she owns through dubious legal maneuvers. Outside of western liberal democracies, it’s rare to find countries with a history of respect for individual rights, for the impartial application of contract law and with strong investor protections in place.

Returning to China – can you really trust the government to protect the interests of foreign investors?

The case for an EM allocation isn’t supported by historic returns. But the financial advisor who recommends EM exposure for a client benefits from the complexity this introduces into performance evaluation. Only the most financially sophisticated will have the tools to establish whether EM added any value. And because EM is rarely a buy and hold strategy, a second timing decision on when to exit also looms. EM is the refuge of the financial advisor obfuscating results with complexity.

All but a handful of the S&P500 does business in EM. Their presence can be used to justify an investment – if Coke is making money in Brazil, why aren’t you? But Coke is so much better equipped to navigate local laws, ownership rights and taxes while still complying with US GAAP standards. And Coke is better situated to calibrate their EM exposure among the countries where they perceive the best opportunities.

If you apply the same logic to another 475 or so members of the S&P500, an investment in the biggest US companies comes with an EM exposure through the filter of US standards and sized according to the collective capital allocation wisdom of hundreds of executive teams and boards of directors.

There’s no reason for the retail investor to make an EM allocation. If your financial advisor recommends it, share the dismal decade displayed above, reject the complexity that benefits him not you and tell him you’re happy with the EM exposure your S&P500 investment provides.

On a different topic, China’s National Energy Administration recently reported, “Based on the overall promotion of oil and gas supply security and green development, oil and gas development enterprises have accelerated the pace of integration and development with new energy on the basis of effectively stabilizing oil and gas and improving the ability to independently guarantee oil and gas resources,” (translated from Chinese by Google).

Don’t be confused by China and renewables. Energy security explains the dual focus on clean energy and coal, because they help reduce China’s reliance on imported oil and gas. Coal provides over 60% of China’s power and is 70% of its emissions. They’re adding new coal plants at more than one a month. Security, not climate change, drives their policies. Why else would a country boost electric vehicle sales powered with the worst of fossil fuels if not for energy security?

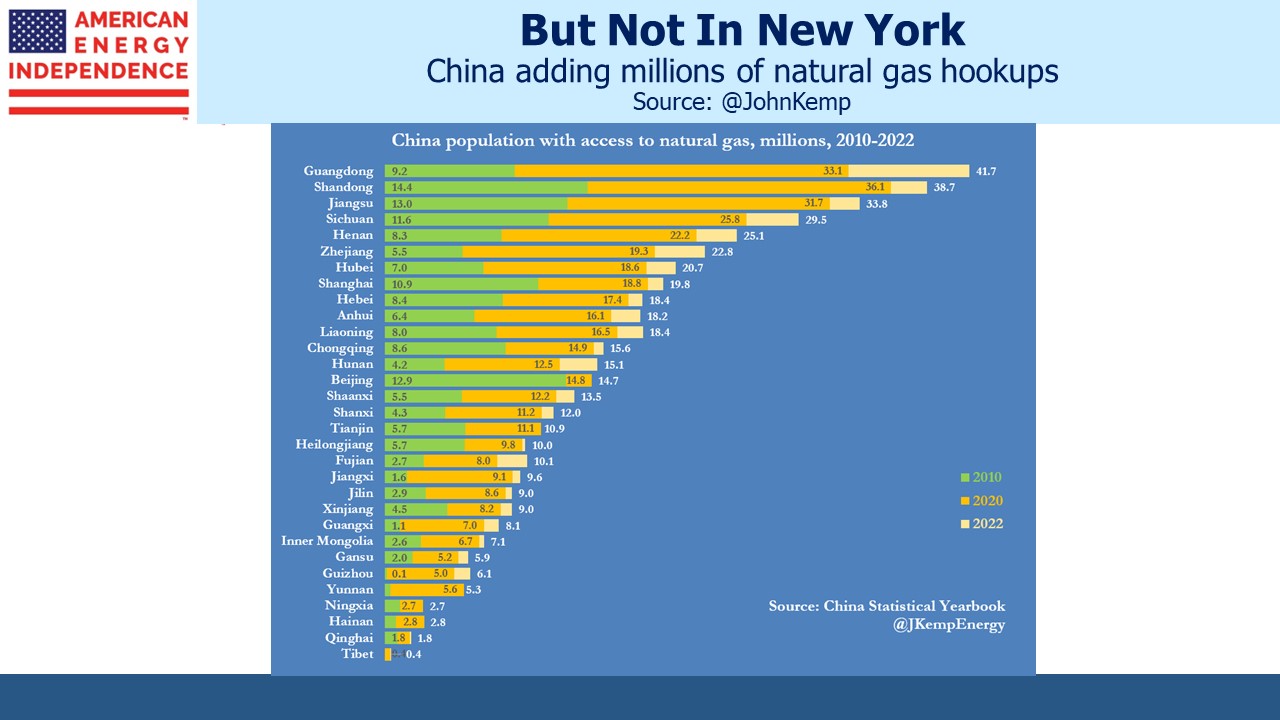

Chinese consumers are being connected to natural gas supply across the country. Many provinces have tripled or more the local population able to use natural gas. In 2022, 15 million new customers were added. This contrasts with New York state which is impeding the ability of new customers to access natural gas.

Do New Yorkers know that China is extending natural gas access while their government does the opposite? Have they bought in to the liberal proposition that we’ll reduce emissions while others grow them? Or are they simply unaware, accepting constrained access to reliable energy in the naive belief that all the world’s emitters are aligned in their efforts to achieve a common goal?

Next time you encounter a New York Democrat voter (and there are many), ask them.

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment: