Down’s A Long Way for Bonds

In my 2013 book Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors, I forecast that interest rates would stay lower for longer than many people thought. The 2008 Financial Crisis was caused in part by excessive levels of debt. Interest rates below inflation are a time-tested way to gradually lessen the burden of a country’s unmanageable obligations. The book’s forecast was right, and more importantly the low rate strategy has succeeded. Household debt service costs have fallen as a proportion of income. U.S. GDP is growing solidly at 2.5% and possibly faster, and at 4.1% the Unemployment rate has fallen to levels that were previously associated with rising inflation. We are enjoying synchronized global growth. In short, regarding Low Rates: Job Done.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has been unwinding its policy of extreme accommodation at a measured pace. Short term interest rates have been lifted from 0% to 1.4%. Bond yields have also been rising, with the Federal Reserve having announced last year the end of their bond buying program. Their balance sheet is close to $4.5TN, and although they’ll continue to reinvest interest income it will eventually start shrinking as their holdings mature.

Lastly, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was stimulative. Falling household debt service, synchronized global growth, no more Fed buying of bonds and tax stimulus are not likely to be supportive for bond prices.

It’s true that in recent years many forecasters have mistakenly expected rates to rise faster than they have. Although the FOMC is not known for frivolity, even they must have chuckled in embarrassment at their own forecasting errors. For several years now, the FOMC has issued forecasts for the Fed Funds rate (i.e. the interest rate they control directly) only to consistently undershoot. They correctly value achieving the right policy rate more than saving their blushes as forecasters.

The challenge for bond investors, as they contemplate the declining value of their holdings, is to identify their fair value. Using ten year treasury yields as a benchmark, what is its neutral level?

The news is not good. As we noted recently (see Rising Rates and MLPs: Not What You Think), the real return (i.e. the return above inflation) on ten year treasuries going back to 1927 is 1.9%. This means that today’s investors should require at least 4% (approximately, inflation plus the historic real return). A 4% yield would deliver the average real return assuming inflation averages 2% over the next decade. Although yields are rising, the current 2.8% ten year yield is inadequate on this measure.

Synchronized global growth and fiscal stimulus are both heading in the wrong direction for a bond investor. Although the FOMC is forecasting 2.5% U.S. GDP growth this year and 2.1% next, they maintain that the long run trend is only 1.8%. This is why they’re projecting higher short term rates over the next couple of years, as well as Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation (their preferred measure) creeping up from 1.5% last year to 2% next year. In a sign that a tightening labor market is stoking wage inflation, Friday’s Employment report included a 2.9% annual increase in hourly earnings, the biggest jump since 2009.

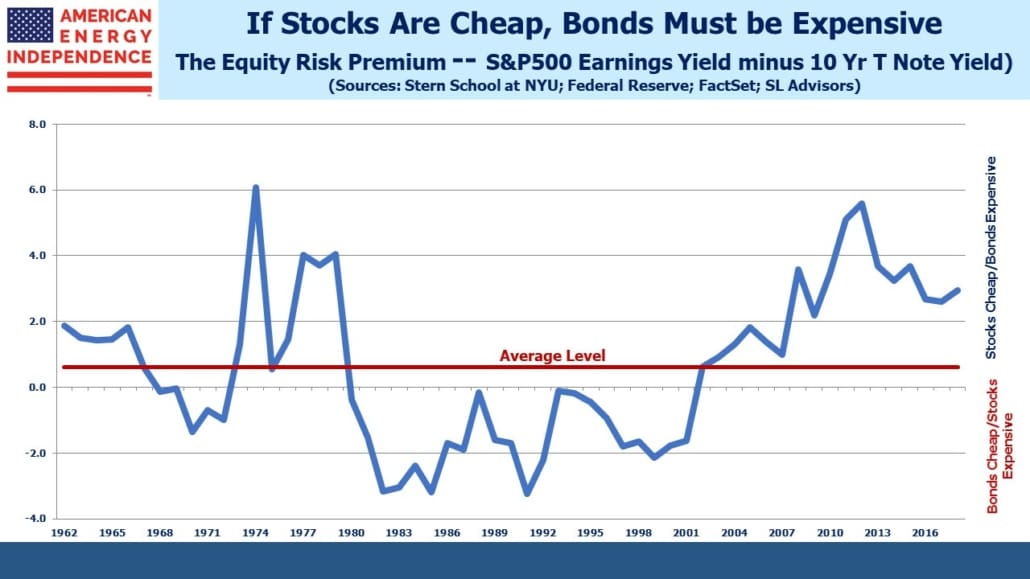

A few weeks ago we revisited the Equity Risk Premium (ERP), which shows that stocks are cheap, relative to bonds. The corollary is that bonds are expensive relative to stocks. Yields need to rise by around 2% to return the ERP back to its 50+ year average. Historical comparisons with real returns and relative valuation to equities both argue that today’s bond market is a poor investment. Although this has been the case for several years, now the fiscal and economic stars are aligned against fixed income. It means that, if yields move up through 3%, taking the prices of many other bond sectors lower, investors considering where valuation support might lie will find little of substance in their favor.

We’re not forecasting that yields will move sharply higher — but we are noting there’s nothing fundamentally attractive about today’s levels. Bear in mind also that few FOMC members can be regarded as inflation “hawks” (does anybody even remember the term?). They’ve been dovish, correctly, for years. If inflation does surprise to the upside, bond investors may need some visible reassurance from new FOMC Chair Jerome Powell that he possesses “inflation-fighting credentials”. Earning such credibility would require raising short term rates even higher.

In September, ten year yields were close to 2% before beginning their current ascent. The last time we saw a 2% increase in yields (i.e. what it would take to return to 4%, approaching long term fair value) was in 1999, when technology stocks were leading us into the dot.com boom and subsequent bust. A generation of market participants has not experienced a real fixed income bear market. As a retired bond trader friend of mine says, when you add all these factors up, for bond prices “Down’s a Long Way”.

Unlike fixed income, energy infrastructure does offer solid valuation support. Moreover, the correlation with bond yields is historically low and likely to remain that way. Few MLP investors expect stable, boring returns anymore and rising GDP growth is good for energy demand. Selling bonds that are substantially above fair value and switching into undervalued energy infrastructure aligns with the macro forces currently at work.

The American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) finished the week -6.5%. Since the November 29th low in the sector, the AEITR has rebounded 7.6%.