Don’t Go Away in May

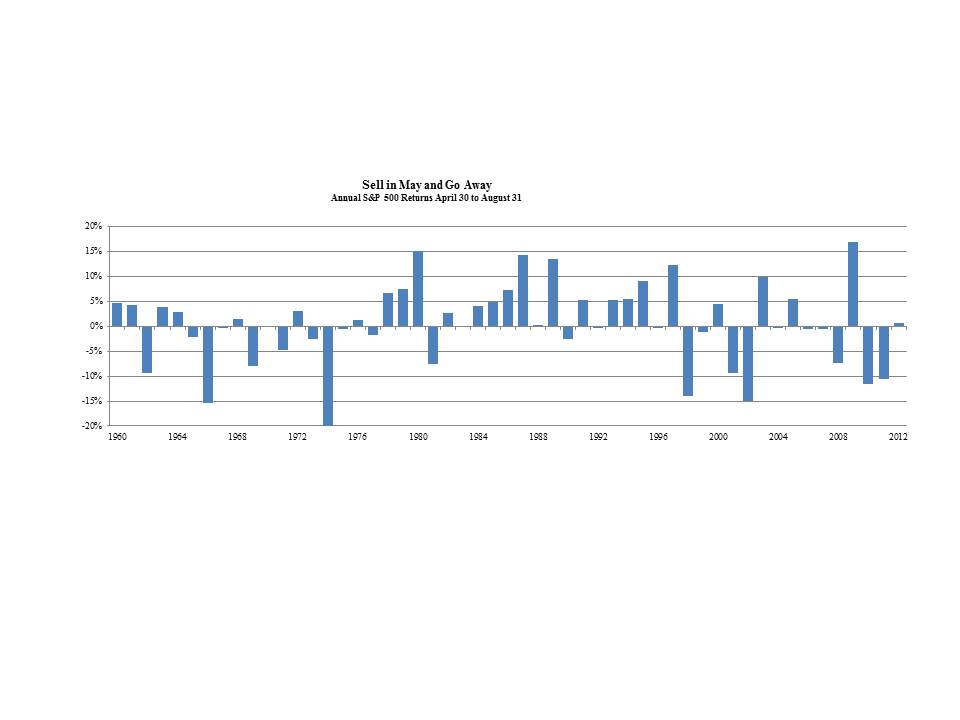

Sell in May and Go Away is an easily remembered rule that worked very well for the past two years. Last year from April 30 to August 31, the S&P 500 lost 11%. Over more than fifty years it’s been sound advice 47% of the time so slightly less effective than a coin flip. However, when it works the results can be memorable, and some spectacular falls in stocks have occurred during this time period including 1966 (-15%), 1974 (-20%), 2002 (-15%) and 2010 (-12%). Recent years have reinforced the rule, with eight out of twelve Summers this millennium representing an unwelcome vacation distraction. Many a holiday has been ruined by portfolio losses on top of that expensive beach house, and no doubt those painful memories persist. However, during the 80s and 90s it worked in only seven years out of 20. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the overall market direction plays a big role. Two thirds of the time Sell in May worked was when the market’s return for the year was negative. So if you’re skilled at selecting good years to be in stocks, you can make your Summers a bit more enjoyable. And for those who want a little bit of an edge, Sell in May followed the pattern set in the first four months of the year 61% of the time. A bad start for the year is a little more likely to continue a few months longer.

In total though, following the Sell in May adage since 1960 would have “cost” an investor on average 0.5% p.a. — more after commissions and taxes are included. Interestingly, most of the 6.3% compounded annual return over this entire period was generated while school was open. As it turns out the Summer that’s about to end ranks #26 with a 1% return, close to the average. This is a seasonal pattern that’s worth following, but barely. However, while Sell in May is not a profitable strategy, for some investors the foregone return by being out of the market may seem a price worth paying for a quiet vacation.

Although macro issues continue to hang over the market and rising prices were caused in part by the calamities that did not befall (i.e. southern Europe still uses Euros), it is notable how many companies reporting earnings during the Summer revised down earnings guidance and generally expressed caution. Even the most economically insensitive companies tempered outlooks. Examples include McDonalds (MCD) who, citing macro headwinds, reported no increase in monthly global comps in July – the worst since April 2003. Coke (KO) experienced declining volumes of 4% in Europe during the second quarter. IBM saw revenues contract globally and profit growth for many companies is relying on improved operating margins rather than top line growth. While it’s never easy to assess whether macro concerns are fully reflected in market prices (or indeed overly reflected) the more cautious outlook recently being provided at the individual company level is noteworthy.

The “fiscal cliff” is also a perplexing hurdle that isn’t yet receiving the respect it deserves. One major investment bank has in its quarterly GDP forecast a fairly smooth sequence of figures from 3Q12 to 1Q13 (+1.5%, +2.0%, +1.5%) that seem to defy common sense. While Washington is consumed with an election countless organizations big and small are planning 2013 capital expenditures and hiring without knowing whether we’ll have a Made in DC recession on January 1st. Anecdotally, many companies are already delaying major commitments until they have greater visibility into 2013 economic activity.

Conventional wisdom is that the lame-duck Congress will amiably defer the mandated tax hikes and spending cuts to later in 2013 and the new Congress, whereas many of us recall that this is the same group of legislators who brought America to the verge of “technical” default during the debt ceiling brinkmanship last Summer (when Sell in May worked). Sometime shortly after the election when the celebrations and recriminations are still fresh, one deeply unhappy party will be expected to compromise with another victorious one. While things will probably work out (because they usually do) a crisis-free experience seems unlikely. The Congressional calendar provides just sixteen days when the House will be in session between Election Day and December 14th when they recess. There seems plenty of room for a miscalculation.

Meanwhile stable, dividend paying stocks are by many measures relatively expensive (most recently highlighted in Barron’s on August 24th). It’s not surprising that low interest rates and widespread global uncertainty have made, say, Kraft (KFT) appealing, because demand for Oreo cookies and cheese is more predictable than Chinese demand for iron ore or the ability of large banks to both reinvent their business models and avoid endless debilitating investigations and fines. To borrow from Michael Lewis in Liar’s Poker, an investor in Goldman Sachs must ask where will the firm find their next “Herman the German” (AKA gullible buyer of hard to understand securities).

One interesting lesson in the field of Behavioral Finance is that many investors apply unreasonably narrow ranges to their forecasts of outcomes. In other words, most of us have a tendency to be over-confident that we are right about our investment decisions. Which is why, in spite of the preceding cautious market narrative we are not heavily invested in cash at present. As coherent as this letter might (hopefully) appear, it could also be dead wrong, and the longer the investment horizon the more likely the outcome is to be good. However while we haven’t sold everything, we have over the past couple of months shifted in our Deep Value Equity strategy away from cyclical exposure and towards companies whose risk is substantially idiosyncratic. Will Corrections Corp (CXW) convert to a REIT, which should cause a meaningful increase in valuation? Will JCPenney (JCP) carry out a successful transformation? Will AIG continue to buy back the government’s shares in it at half of book value? Will Warren Buffett repurchase shares in Berkshire (BRK-B) if they fall to within 10% of book value? Will Burger King (BKW) and Family Dollar (FDO) improve their operating metrics towards those of their peers? All of these are holdings in our Deep Value Equity strategy, along with cash and gold miners (GDX) to protect against deflation and reflation respectively.

Our Hedged Dividend Capture Strategy is very low turnover by design and so retains its positions in stable, low beta dividend paying stocks such as MCD, KO, KFT and others mentioned above. We believe the combination of these long positions with a short S&P500 hedge results in a portfolio uncorrelated with equities. Performance for the year in this strategy is flat, since the +13% return in the S&P500 has generally favored higher beta names with low or no dividend. Interestingly, without Apple (AAPL) the S&P500 would be up 2.2% less than it is so far this year, 16% of its return. Just being short AAPL has reduced performance in this strategy by a little over 1%. It’s an amazing outcome considering AAPL began the year with a 3% weighting in the S&P 500 (it’s now over 4%). We’re not even negative on AAPL, we’re simply short it through its inclusion in the S&P 500.

Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) continue to look attractive with 6%+ yields and solid growth prospects. Developing new energy infrastructure to support the growing domestic production of oil and natural gas will remain a vital element of energy independence for many years to come. The likelihood of low bond yields for the foreseeable future combined with the inflation protection such assets afford through their ability to raise prices annually make this a useful income-generating investment for many investors. In August we reduced our position in Sunoco Logistics Partners (SXL) in those accounts where this long-held position had become an overweight through strong performance and reallocated towards Oneok Partners (OKS).

All of which goes to show that, had we embraced Sell in May for many sound reasons at the beginning of the Summer we would have been dead wrong then too.