Different Audience, Different Energy Policy

Last week’s Economist magazine included an illuminating op-ed by Nigeria’s vice-president on “the hypocrisy of rich countries’ climate policies.” Like most emerging countries, Nigeria is simultaneously pursuing two goals; improving the access of Nigerians to energy, while reducing the country’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions.

Vice-president Yemi Osinbajo’s essay neatly captures the dilemma his and other governments face. He wants to “close the global energy inequality gap.” He noted that the 48 sub-Saharan countries of Africa (excluding South Africa) are home to a billion people and use less electricity than Spain’s population of 47 million. Osinbajo wants Nigeria to achieve annual power output of at least 1,000 kilowatt hours per person. Today per capita electricity consumption in Nigeria is less than a fifth of this goal. With the country’s population of 206 million expected to double by 2050, the vice-president estimates electricity output will need to increase by 15X.

Dramatically increasing domestic power generation is a popular message designed to resonate with Nigerian voters. That part of Osinbajo’s essay is targeted at his domestic audience. Then he turns to his audience of foreign OECD governments, noting that Nigerian president Buhari has “pledged that Nigeria will reach net-zero emissions by 2060.”

ClimateActionTracker.org estimates that Nigeria’s GHG emissions will increase by 21% over the next decade. The “Almost Sufficient” grade is generous since they’re set to increase faster than ever.

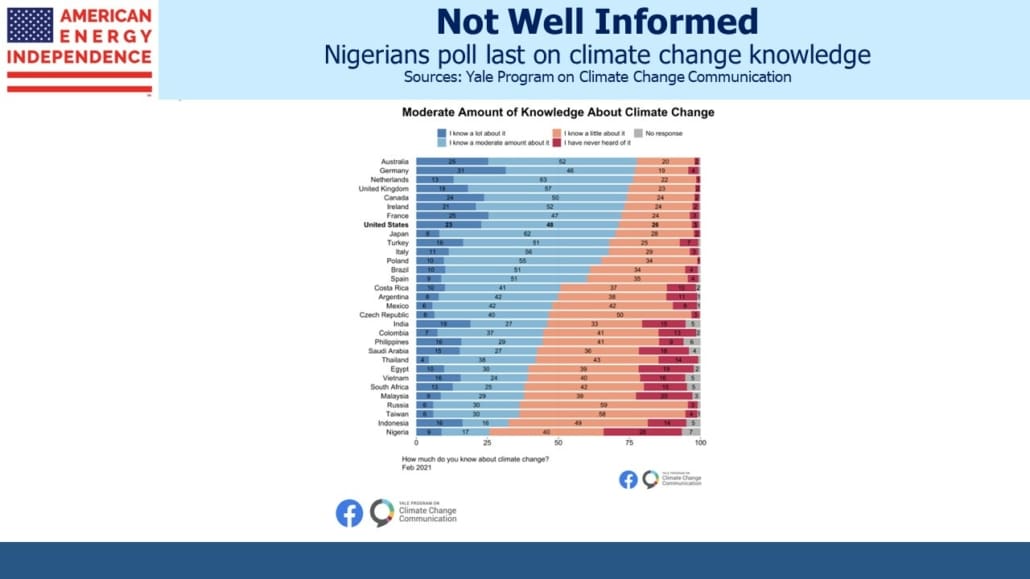

Climate change is not big concern among Nigerians. Last year the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that Nigeria polled dead last out of 31 countries on knowledge of the topic, with only 26% responding that they knew “a lot” or “a moderate amount” about it. The US equivalent was 71%. Only 58% of Nigerians were “very or somewhat” worried, close to the US at 68% and far behind Mexico (95%). That Nigerians and Americans are similarly worried about climate change is ironic because the US, with a per capita GDP 10X Nigeria’s, is far better able to pay for mitigation.

The result is that Nigeria, like many other poor countries, offers very different messaging depending on its audience. Domestically they prioritize raising living standards, which includes access to electricity. Internationally they offer solemn pledges to reduce GHG emissions.

The COP26 meeting in Glasgow last year pledged $8.5BN to South Africa to accelerate their energy transition, although it’s still unclear how or when this will be funded. Nigeria believes it needs a green package of $10BN per year over two decades, which will cover half the capital required to meet its net-zero pledge. Plainly, Nigeria won’t reduce emissions without substantial financial support from the US and other rich world countries.

Nigeria’s power sector generates about 12 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, less than one per cent of the US at just over 1.5 billion tonnes. If Nigeria’s goal of adding 15X more output was done with the same energy sources, it would add what 25 million Americans generate. It sounds modest. But applied across the rest of the non-OECD world and not limited to just the power sector, growth in emerging economies could easily offset whatever reductions the rich world can achieve.

There’s a moral argument that the OECD countries who have used up most of the atmosphere’s assumed capacity for CO2 should cut their emissions aggressively while paying non-OECD countries to curb theirs. It’s a complicated issue. We’ll never subsidize China’s investments in clean energy. Moreover, western countries didn’t impose half a century of growth-impeding socialism on China or India, which they only began to shed in the 1990s. Both are making up for lost time, which is why their living standards are catching up. China is now the world’s biggest emitter, spewing out 2X the US which is number two. India is third. The world’s climate will be determined by China, India and other emerging countries.

The challenges are simple to articulate, if complex to solve. Poor countries are both more vulnerable to the negative effects of a warmer planet, and less motivated to tackle the issue without substantial OECD financial and technological help. Without a massive commitment, the world will learn to adapt to increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere.

US climate extremists have successfully forced New England to import liquefied natural gas by, for example, blocking new pipelines from Pennsylvania. Their conviction that such efforts somehow address the non-OECD challenge outlined above betrays a misunderstanding that would be comical if it didn’t have as its objective condemning Americans to cold and darkness. It’s exacerbated by President Biden’s promise to, “…deploy clean energy for the benefit of all Americans—with lower costs for families, good-paying jobs for workers.”

US political leaders steer so far from confronting the issues, including higher costs and substantial foreign aid, that they’re encouraging wholly unrealistic and inadequate policy responses. This is why global demand for natural gas will continue to grow. Like western politicians, Nigeria’s v-p is tailoring his message to his audience.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.