Deciphering the FOMC’s Tea Leaves

Last week’s FOMC meeting for once gave the market something to ponder. The $120BN of monthly bond buying looks set to taper before the end of the year, and to be down to zero by next summer. Fed buying of mortgage-backed securities has been especially superfluous, as shown by the red-hot housing market.

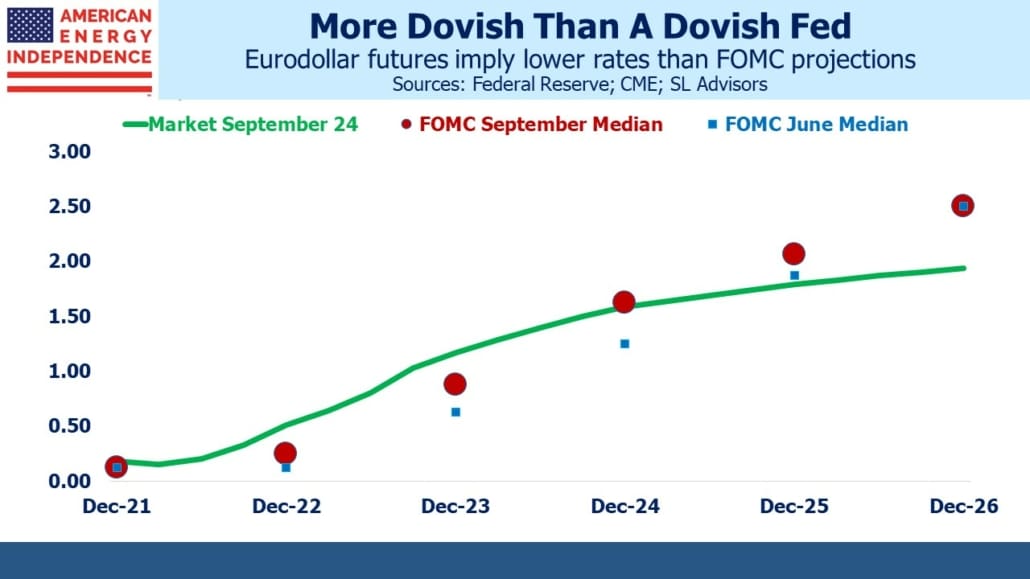

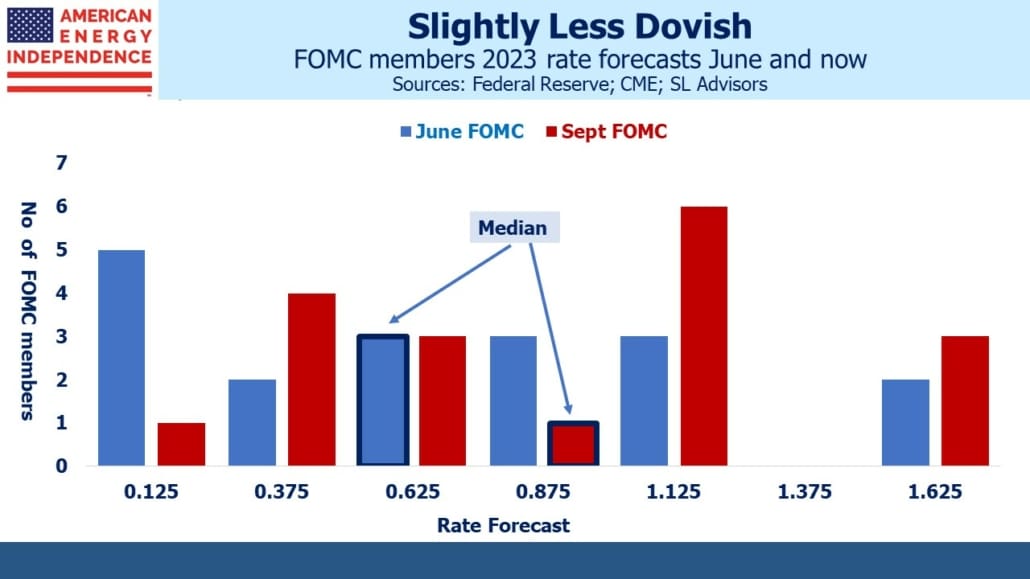

The market interpreted a more hawkish message, and eurodollar futures yields rose to price in a slightly more aggressive pace of tightening. It’s true that median rate expectations of FOMC members edged up compared with June. But the range of forecasts remains very wide. This may be one of the reasons Fed chair Jay Powell continues to advise against too close a reading of the projection materials, even though we all pore over them with great care as soon as they’re released.

To use one example – the median FOMC member’s forecast for the Fed Funds rate at the end of 2023 rose, from 0.625% to 0.875%. A 0.25% increase, even over two years out, seems significant. But as the chart shows, views within the FOMC vary widely. One member doesn’t think they’ll have raised rates at all by then (down from five who held that view three months ago). There’s still a gaping 1.5% gap between the high and low forecast. Committee discussions about the outlook must be lively, at least within the constraints of what’s plausible when discussing monetary policy.

Most FOMC members continue to expect to raise rates faster than implied by eurodollar futures, which offers an opportunity for those able to participate. The spread between Dec ‘23 and Dec ‘25 futures remains too flat – it came in briefly on Wednesday along with the twos/fives yield curve following the release of the FOMC statement but widened again the next day.

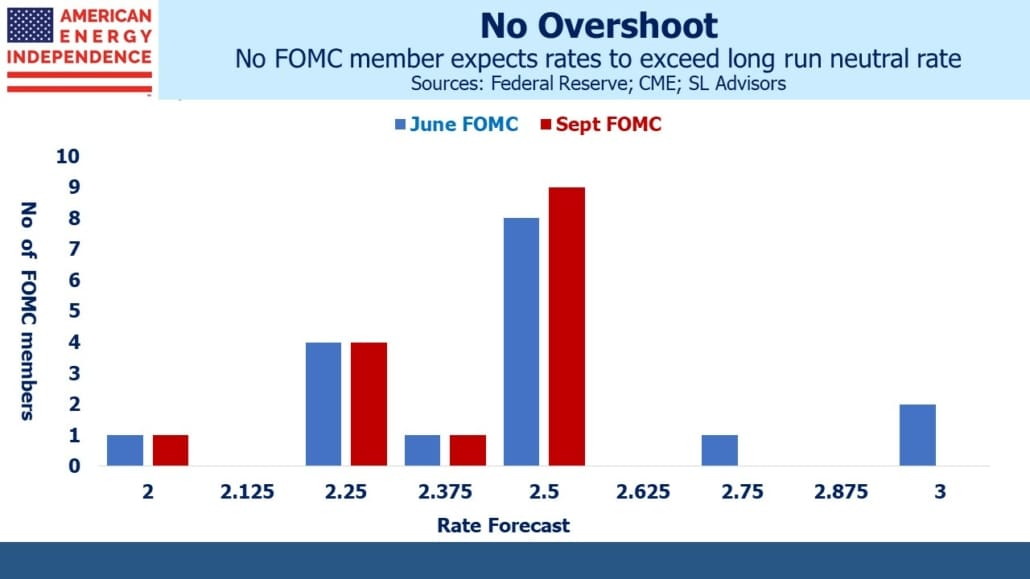

Another interesting evolution concerned FOMC members’ “longer run” outlook for short term rates, the so called equilibrium rate. For years this has been declining, along with real rate or the premium markets demand over inflation. Chair Powell has discussed “R-star” in the past. R-star is the Fed’s assumed equilibrium real rate, or the margin over inflation they should target for neutral policy. R-star of 0.5% added to 2% inflation is how they’ve arrived at a 2.5% neutral rate, and it’s the reason today’s FOMC appears so dovish. A lower equilibrium rate means there’s less room to cut rates when needed, which makes it harder to achieve their inflation target. Hence the new policy adopted just over a year ago of allowing inflation to exceed their 2% target rather than acting pre-emptively to prevent it.

So it’s notable that FOMC members’ “longer run” forecast of short-term rates came down somewhat. Only 15 of them offered such a forecast, down from 17 in June and short of the 18 who provide annual rate forecasts through 2024. It’s unclear why an FOMC member would provide less than a complete set of forecasts, but the missing ones were probably more hawkish because all the three forecasts in June above 2.5% were gone last week.

At the same time, inflation forecasts have edged up slightly, with core Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation (the Fed’s preferred measure) expected to run at 2.2% in 2023, up 0.1% from June. Most notably, although 2.5% is their median long run neutral policy rate, only one FOMC member expects rates to be above that level even by 2024.

What conclusions should one draw from all this numerical insight into the Fed’s thinking? Their opinions vary widely, but they expect to raise rates faster than implied by the market. But they are optimistic — even though they’ve had to constantly revise their inflation forecasts higher, they overwhelmingly expect inflation to return to their 2% target without having to raise rates above the 2.5% neutral level.

Moreover, the tone of the FOMC is very dovish, at least to this observer of 40+ years. There are no hawks in the traditional sense. The notion that monetary policy can be used to moderate income inequality, as Jay Powell has suggested in the past, has not been suggested by his predecessors. It’s easy to imagine the dilemma such a view will pose when it comes time to tighten rates. There will be a healthy debate about whether lower income Americans are hurt more by inflation or higher rates, and the consideration of income inequality along with the level of employment will cloud the right course of action.

It’s also likely that Democrat administrations will apply a monetary policy litmus test when selecting future FOMC members, in the same way that Supreme Court candidates’ past rulings are examined for signs of reliable political bias. For example, Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren, who just announced his early retirement, is an outspoken critic of the Fed’s bond buying (see The Fed’s Balance Sheet Has One Way To Go). His replacement is likely to be more dovish.

The bottom line is that, while short term rates will inevitably rise, the Fed has shifted to care more about maximizing employment than protecting savers. Investors should position accordingly.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: