Could Oil “Super-Spike” Above $150?

In July, Pierre Andurand’s hedge fund, Andurand Capital, lost 15% on bullish crude oil bets. Oil was weak in July, but is up 21% in 2018. Notwithstanding this correct outlook, his fund is -5% for the year. Few things are more frustrating for a manager or his clients than losing money on a profitable call.

Putting aside the challenges of hedge funds, which we have amply covered in years past (see The Hedge Fund Mirage; The Illusion of Big Money and Why It’s Too Good To Be True), a bullish outlook on crude enjoys solid fundamental support. Andurand once ran a hedge fund that profited mightily during the 2008 financial crisis, only to fold following large losses in 2011. More recently though, his calls on oil have been better than most (see Fund Chief Survives Oil’s Swings), including correctly forecasting the 2014-15 collapse. Few of his peers successfully navigated this period. Reportedly, Andurand sees a multi-year bull market that could eventually reach $300 a barrel. Bernstein Research, whose deep investment analysis is widely respected, has warned of a “super-spike” above $150 a barrel.

Both supply and demand for crude oil are relatively inelastic over periods of a few quarters or so. Global transportation relies heavily on refined petroleum products. Higher prices discourage some trips, but for the most part miles driven and flown don’t dip much with higher prices. Bringing on new supply typically takes several years. So over the short run, small shifts in demand or supply disproportionately move prices.

Global crude oil demand rose by 1.7MMB/D (Million Barrels per Day) last year and in 2016, up from the ten year average of 1.1MMB/D. Demand growth is driven by developing countries, especially China and India. But far more important to a balanced market is depletion of existing oilfields, something that receives little attention. Output from most plays peaks early in their operational life, when underground pressure is most effective at pushing oil to the surface. Thereafter, production steadily declines. Estimates vary, but most analysts agree that 3-5MMB/D is the global drop in annual production from existing plays, absent any new recovery-enhancing investments.

This year the Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that the world will consume 100 MMB/D, a record. In order to offset depletion plus demand growth, new supply of around 5-7MMB/D is required.

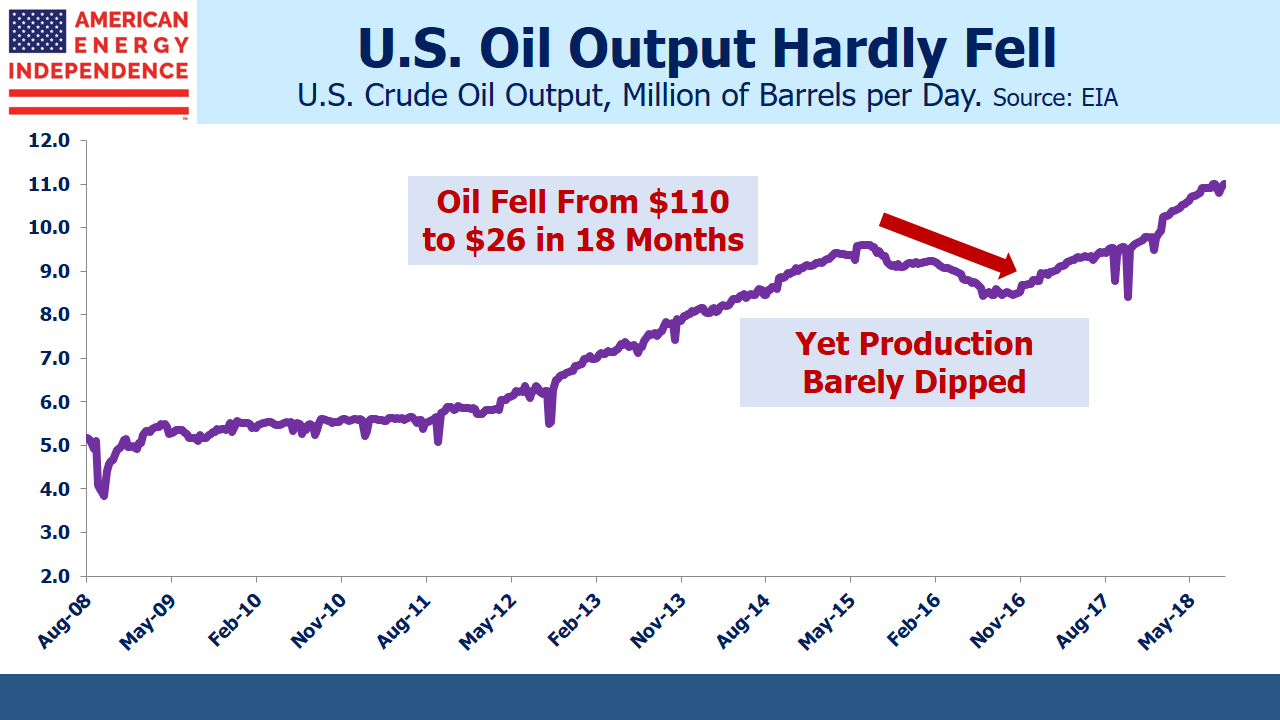

Following the oil price crash 2014-15, energy companies adopted greater financial discipline and planned for lower oil prices in the future. The combination of higher required returns and lower assumed prices has had a chilling effect on investment. The U.S. Shale Revolution is at least partly responsible. U.S. output barely dipped during the 2014-15 collapse. Although low prices weren’t sustained for long, the episode caused subsequent projects to be evaluated against the possibility of a repeat. For example, in April BP’s chairman said they were, “still working with the assumption that this is going to be a world with an abundance of oil.”

Major oil projects have always had risk to input costs and demand over the ensuing decade or longer. But today, those risks are even harder to quantify. It’s generally believed that oil demand will peak within a generation, yet growth in recent years has been as high as ever. Although Electric Vehicles (EVs) have many enthusiasts, sales growth of gasoline-chugging cars easily outpaces EVs in China, which is why crude demand keeps growing.

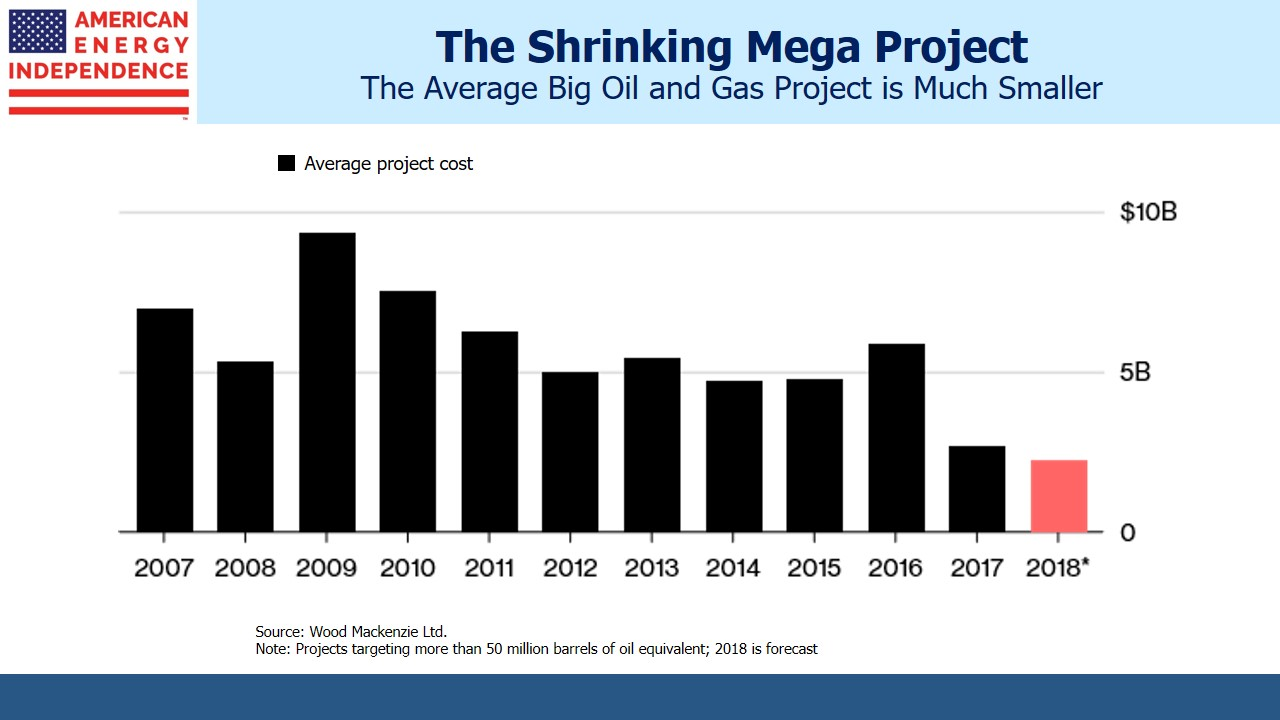

Improved financial discipline, wariness of a second Shale-induced price collapse and uncertainty around EV growth are three significant factors impeding investments in new supply. Taken together, these three factors have created greater risk aversion than the industry has shown in the past.

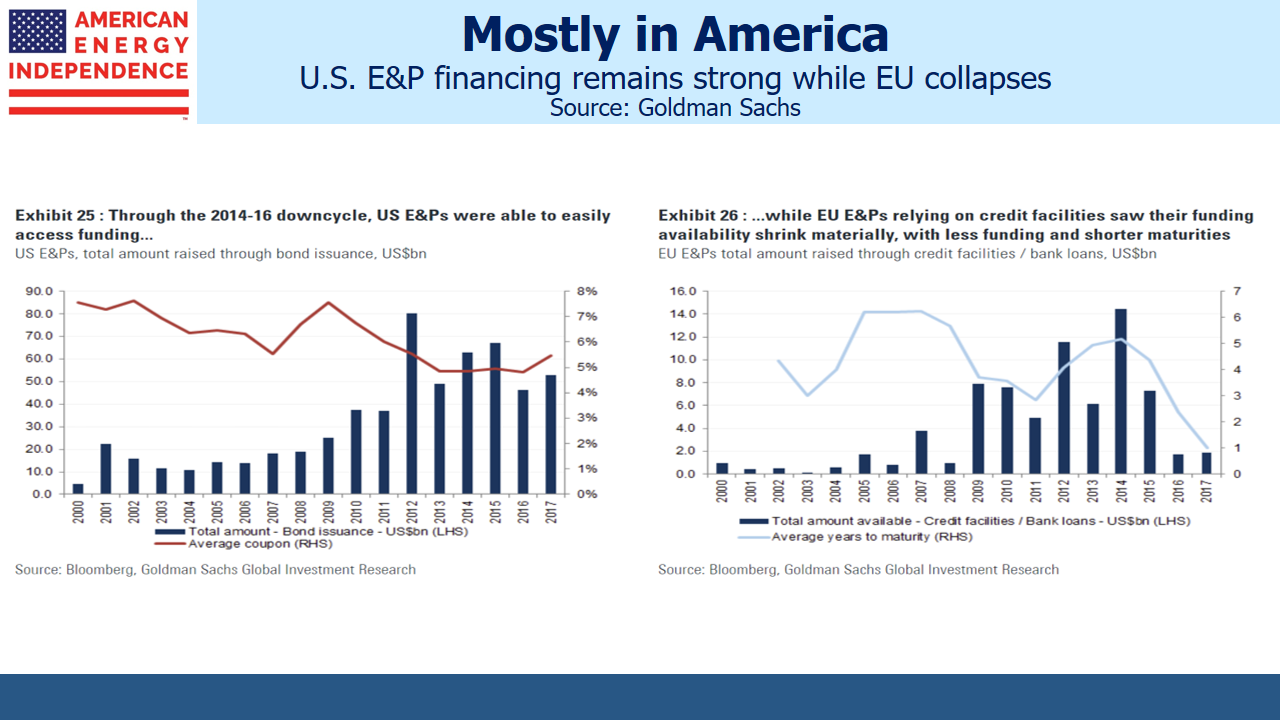

Consequently, capital invested in conventional projects remains low and projects are more modest. Companies are favoring “short-cycle”, whose smaller up-front investment consequently gets repaid more quickly with greater IRR certainty.

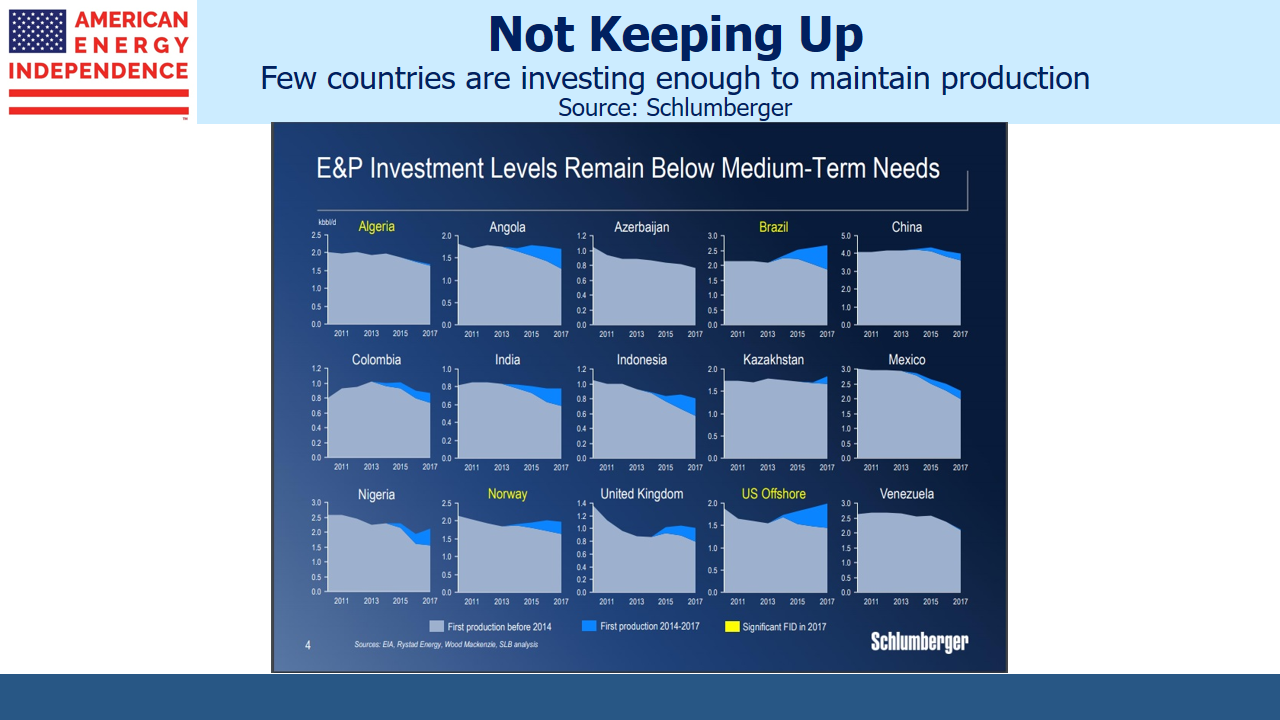

However, there just aren’t enough short-cycle projects available, which is causing concern within the industry. Schlumberger CEO Paal Kibsgaard warned that, “It is, therefore, becoming increasingly likely that the industry will face growing supply challenges over the coming year and a significant increase in global exploration and production investment will be required to minimize the impending deficit.” Bernstein Research concurred, “Investors currently calling on exploration and production companies to return more cash to shareholders at the expense of funding future production may also come to regret their strategy.”

There are many examples of countries underinvesting in maintaining existing levels of production.

Because less risky, short-cycle projects are mostly shale plays in the U.S., a stark difference in financing has opened up between America and Europe. EU bank financing for Exploration and Production, always far smaller than in the U.S., has collapsed in recent years.

Although Saudi Arabia is believed capable of producing as much as 12.5 MMB/D for a few months, many observers feel this is unsustainable. U.S. shale is one of the few areas of growth. Permian output in west Texas is expected to average 3.3 MMB/D this year and 3.9MMB/D in 2019. Yet, infrastructure constraints recently caused the EIA to trim its outlook for U.S. 2019 production from 11.8MMB/D to 11.7 MMB/D, up 1 MMB/D versus this year. Concern that U.S. production could lead to another price drop is limiting new global investment – yet, the most optimistic forecasts of U.S. output show that significant additional new supply beyond US shale is going to be needed.

A determination to avoid past mistakes of unprofitable oversupply is likely to lead to the opposite; an undersupplied oil market. The question is, how high must crude go to satisfy the new profitability goals and other concerns of the integrated oil companies. Many fear that $100 a barrel will be insufficient – and the market is poorly positioned for any supply disruptions, perhaps caused by Iran or some other geopolitical shock. Another Shale-induced price collapse, falling demand due to EVs and new-found financial discipline represent long-term concerns inhibiting the search for new discoveries.

Oil needs to be high enough to compensate for all three risks. Since today’s prices aren’t high enough to stimulate enough new investment, oil should move higher. This will encourage conventional investment, but will also test the limits of the U.S Shale Revolution in growing output. To bet on increasing oil and gas volumes in the U.S., invest in the network of infrastructure that moves these supplies to market.

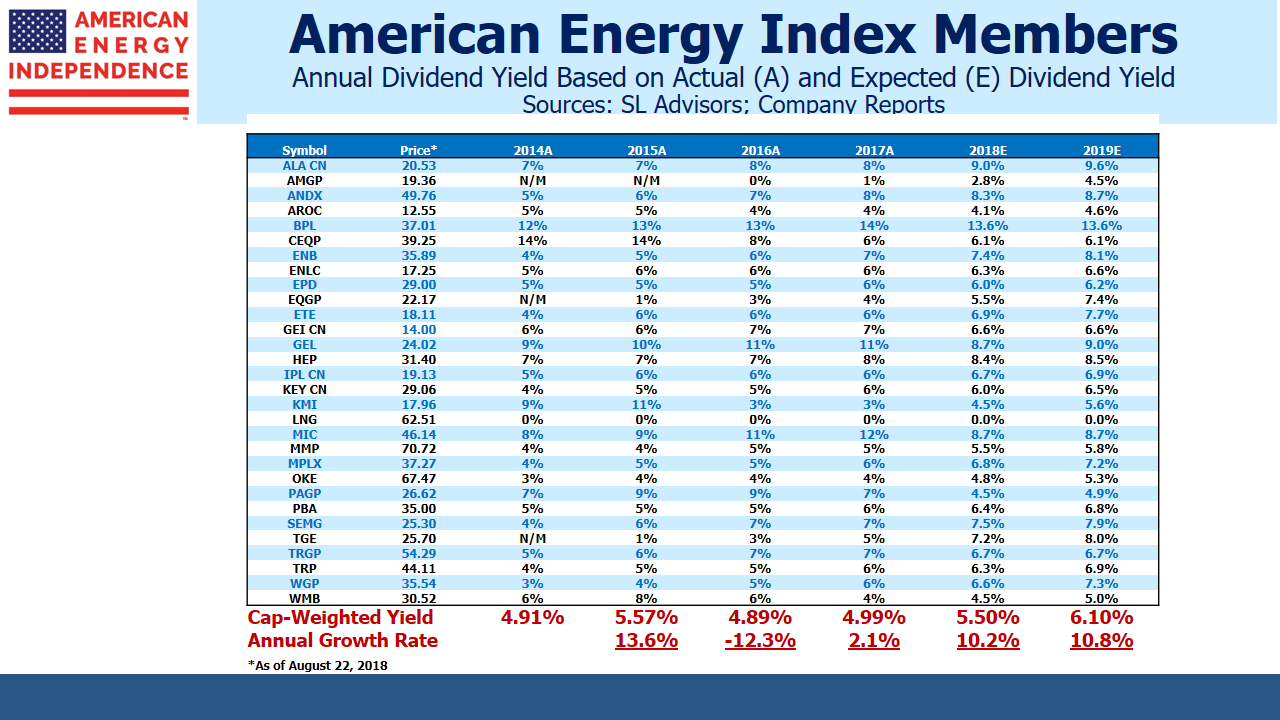

The components of the American Energy Independence Index are growing dividends at 10% per annum.