Comparing Conoco Phillips with MLPs

Around ten days ago Conoco Phillips (COP) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both released their 4Q15 earnings, and held conference calls on February 4th to discuss them. This coincidence of reporting is about all they have in common, but it caused us to look a bit more closely at an energy company (COP) that truly has commodity price exposure and what it’s doing about it.

Around ten days ago Conoco Phillips (COP) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both released their 4Q15 earnings, and held conference calls on February 4th to discuss them. This coincidence of reporting is about all they have in common, but it caused us to look a bit more closely at an energy company (COP) that truly has commodity price exposure and what it’s doing about it.

COP announced a two-thirds cut in their dividend, a completely understandable move because they really are financing it with debt. The problem with an Exploration and Production (E&P) company like COP is that they have to keep replacing their assets. Hydrocarbons produced are assets no longer available to generate future revenues, and so they keep investing in new future production. Consequently, COP’s $3.3BN of 2015 EBITDA was dwarfed by $10BN of capex resulting in negative free cashflow (FCF). They lost $3.50 per share. The company closed out the year with half the cash with which it started ($2.4BN versus $5.1BN) and on top of that their proved reserves fell by 19%, from 8.9 BBOE (Billions of Barrels of Oil Equivalent) to 8.2 BBOE. Incidentally, COP’s 2015 Depreciation, Depletion and Amortization (DD&A) was $9BN, pretty close to their capex. Their new investments were approximately equal to the hydrocarbon assets they extracted and sold. In 2016 their DD&A is likely to exceed their capex by $2BN. They are running very hard and not even moving forward. 2015 was a year COP will happily forget – they lost money, used up half their cash and saw their reserves drop. They have nothing to show for it.

It’s hard to know how to value COP, and especially hard to compare them with an MLP (which is where we’re going). Neither their free cashflow yield nor their P/E multiple are meaningful since both are negative. On an Enterprise Value/EBITDA (EV/EBITDA) basis they’re priced at 15.4X based on 2016 guidance, which incorporates a 36% slashing of their capex budget to $6.4BN. This multiple flatters COP and all E&P companies though, because it backs out depletion and depreciation although their future EBITDA is dependent on continuing growth capex to replace what’s gone.

COP’s dividend cut was a belated acknowledgment of the obvious, which is that they don’t generate any cash to pay a dividend so are funding it with debt. In fact, COP operates in the way that many MLP critics assert is prevalent with midstream infrastructure businesses, although there are substantial differences between the assets of an E&P company (hydrocarbon reserves which are used up) and pipelines which last for decades and don’t require perennial replacement (although they do require maintenance).

MMP reported solid earnings and generates Distributable Cash Flow (DCF), a measure somewhat analogous to COP’s FCF (although MLP critics will disagree on this point). MMP’s DCF covers their distribution, whereas COP really has no business paying a dividend. MMP’s EV/EBITDA, in which their EBITDA is more reflective of FCF generation because its assets are not naturally depleting, is 15.3X on 2016 guidance, roughly the same as COP’s.

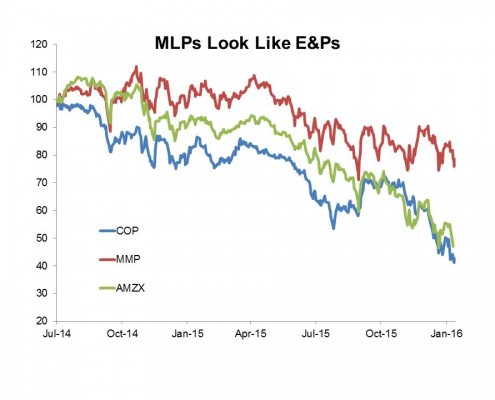

Now it’s true that COP has tracked the Alerian Index (AMZX) more reliably than MMP, which is to say MLPs have behaved like an enormous cash-consuming owner of depleting assets rather than the cash-generative owner of sustainable assets that they are (chart source: SL Advisors). The few E&P names in the Alerian index have been dumped following distribution cuts (reliable distributions are one of the the rules for inclusion), so AMZX no longer includes E&P businesses. MMP has outperformed AMZX, and yet its valuation fails to differentiate it from COP. It has been dragged down by its sector.

We continue to think that the ongoing collapse in MLPs is reflective of their financing model and rigidity of the investor base (see The 2015 MLP Crash; Why and What’s Next). Traditional MLP investors are U.S. taxable, high net worth (HNW) individuals. The arrival of smaller retail investors through mutual funds and ETFs for a time met the increased need for growth capex that traditional MLP investors, who like their distributions, didn’t want to finance by reinvesting everything they received. The retail investor was the marginal buyer, for a while. The surprise has been that upon his exit, new sources of financing have required a substantial price discount. MLP proponents have written for years about the institutionalization of the sector. The evidence clearly shows that once you exclude institutional money managers of retail money, the true institutional investors of public equities (pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments and foundations) are not natural MLP investors because of the tax barriers.

Deciding the sector is cheap and then identifying a manager and implementing is a deliberate process, and while we see some evidence that it is under way, the buyer of an MLP today is most likely still the traditional HNW taxable investor. Given the collapse in prices, he’s not very enthusiastic. In this way, the MLP sector is unlike any other sector of the U.S. equity markets where capital can move in more opportunistically. Eventually, institutional investors will commit more meaningful capital, but it takes time. Most of the publicly listed MLP funds are terribly tax-inefficient (see The Sky High Expenses of MLP Funds), although not ours. As well as selecting a manager to oversee an MLP portfolio, a non-tax paying pension fund must decide to file a tax return (as direct holdings of MLPs would require). These are not trivial decisions. Count the cheerleaders for the “institutionalization” of the MLP sector among those whose views were aspirational rather than realistic.

We are invested in MMP.