Climate Policies Confront Reality

Casually following news of the energy transition can create the impression that the world is a few years away from running on solar power and windmills. The reality is that climate extremists have propagated two impractical beliefs that are impeding policies based on pragmatism. One is that solar and wind are the complete solution. The other is that emerging economies are similarly committed to reducing emissions.

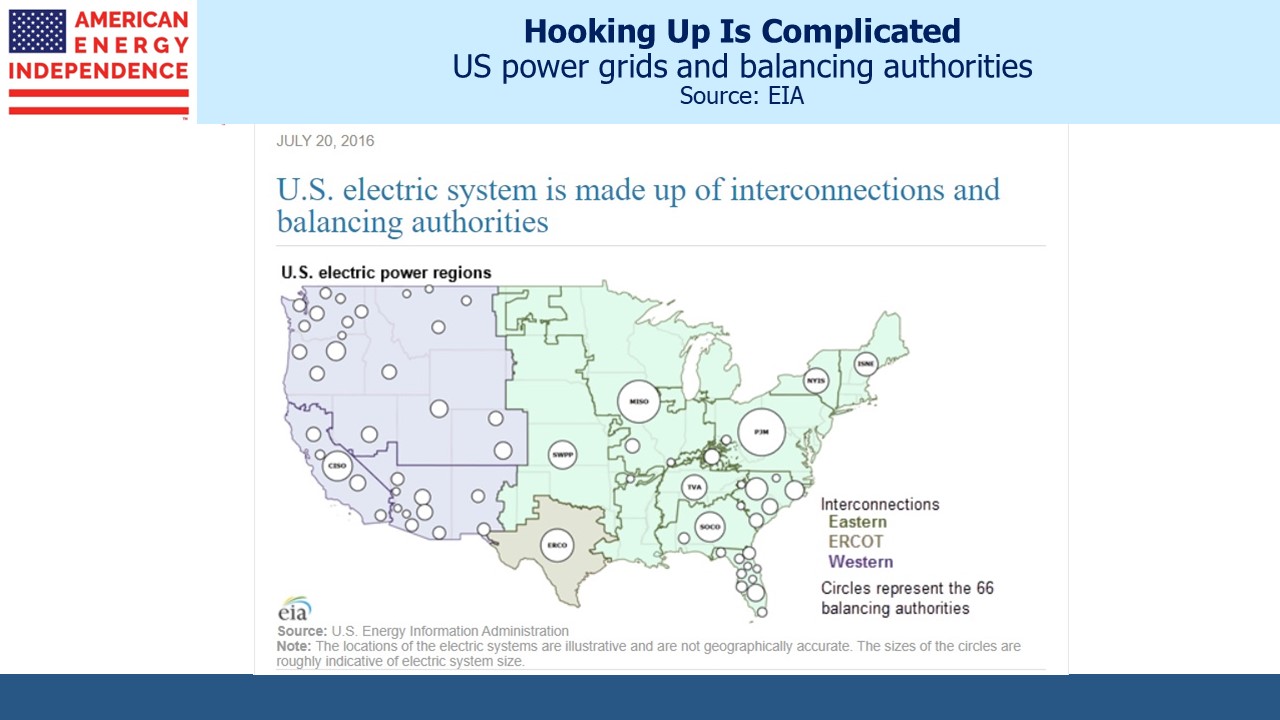

Starting with electrification – the NYTimes recently acknowledged the growing delay in connecting solar and wind projects to the grid. The US has three grids — Eastern, Western and ERCOT which is approximately Texas, along with 66 balancing authorities. New sources of power supply have to negotiate access to this system, which often requires adding power infrastructure.

PJM Interconnection, a regional grid running from Illinois to New Jersey, has frozen new applications to add power until 2026 while they process the backlog. Developers often have to pay for grid upgrades. A wind farm in North Dakota was asked to pay millions of dollars to upgrade transmission lines hundreds of miles away in Nebraska and Missouri.

Across the US approvals now take on average four years. It’s estimated that less than a fifth of new solar and wind projects get connected. Climate extremists have become adept at using court challenges to vacate environmental permits issued to pipeline projects. But the same approach can also delay infrastructure to support renewables, because NIMBYs are not a coordinated political force. Permitting reform is sorely needed.

The Energy Information Administration reports that renewables were almost two thirds of investment in new power output in 2021, with natural gas 22%. There were no new coal plants. Natural gas often enables renewables by compensating for their intermittency.

Owners of Electric Vehicles (EVs) often struggle with charging. In my experience everyone loves their Tesla, but I recently took an Uber ride in Pennsylvania where the driver reported a daily one hour wait to recharge her (Uber-owned) EV. She wasn’t willing to spend the $6K required to install an EV charging outlet in her home. Most EV owners I know have a second car for long trips.

EVs will continue to gain market share, and the US is a relative laggard. Cheap gasoline, a preference for big cars and high annual mileage have slowed EV penetration outside California. Like many people, I’m going to wait until improved charging speed and availability makes buying an EV an upgrade to quality of life.

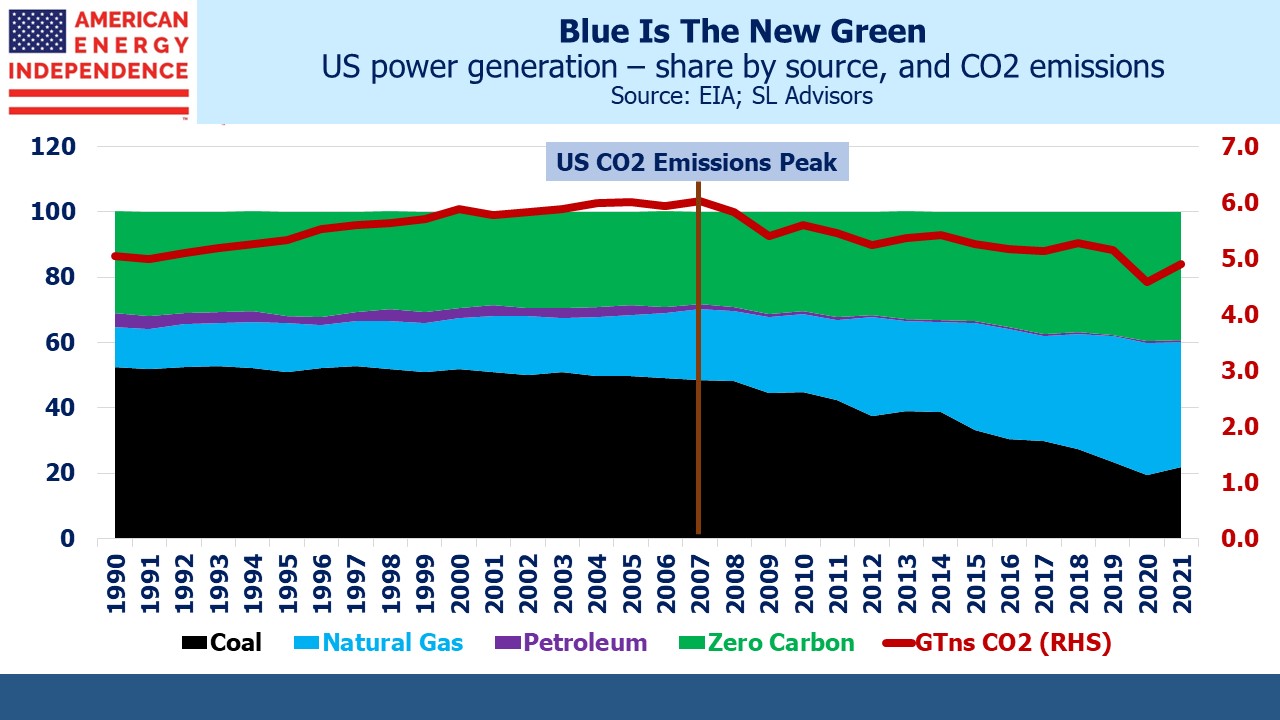

It’s also easy to think that our efforts on climate change here in America are critical to solving the global challenge of reducing CO2 emissions. We have had a lot of success over almost two decades. US CO2 energy-related emissions peaked in 2007 at 6 Billion Metric Tonnes (Gigatonnes, or GTns), and are now 18% lower. This has come about in part because coal dropped from 48% to 22% of power generation. Natural gas rose from 22% to 38%, compared with zero-carbon (which includes reliable nuclear and hydro as well as intermittent solar and wind) which rose from 28% to 39%.

This is why a sensible strategy to reduce emissions would eliminate what remaining coal we use and replace it with natural gas and nuclear. Climate extremists are purists if not practical.

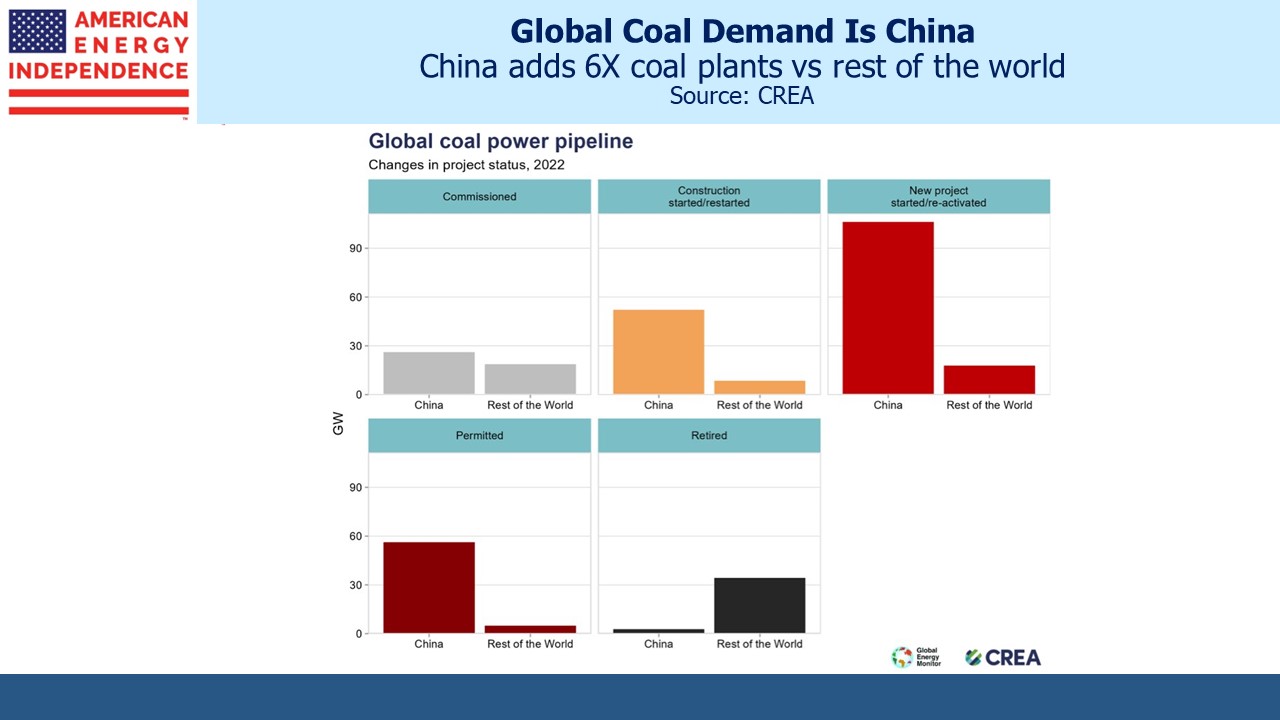

Emerging countries are defining the world’s CO2 emissions, and they continue to invest in coal burning power plants. At the COP21 in Glasgow India promised to “phase down” coal, which practically speaking means its use will grow more slowly than other sources of energy. Old coal mines are being reopened, and coal executives expect their output to be required for at least another quarter century. Its fastest growing coal mine is scheduled to triple in size.

China’s coal use dwarfs the rest of the world. The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) calculates that 85% of the planet’s planned new coal projects are in China. Living standards can’t improve without increased energy use, but China’s policies render other countries’ efforts irrelevant. Or our efforts allow China to do less, depending on your perspective.

No review of climate policies would be complete without reference to that obnoxious little girl Greta Thunberg, who once preached to the rest of us from the UN (“How dare you”). Betraying her discombobulated understanding of the world’s energy needs, she recently accused Norway of “green colonialism” because of plans to build an onshore wind farm in the middle of an area where reindeer graze.

Natural gas remains the world’s best hope for serious emissions reduction, as it has been in the US in spite of sometimes incoherent opposition from climate extremists.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: