Clean Fossil Fuels May Be Coming

Tokyo enjoys on average 1,800 sunny hours a year, less than half of sun-drenched Arizona. It’s also subject to extreme weather, such as typhoons. Arizona may be a candidate for solar power, but if Japan’s capital relied on the sun for its electricity, it would require battery back-up to provide the 25 Gigawatts (GW) its residents use for each day that bad weather, including typhoons, blocked its power source.

That’s 600 GWh per 24 hours. By 2021, Southern California Edison is planning a single system capable of running 100 MW for four hours. Tokyo would need 1,500 of them for 24 hours of back-up, sitting mostly idle until called into action by an extreme weather event.

This thought experiment is used in an interview with Bill Gates, where he illustrates the challenges facing renewables in meeting the world’s energy needs. Elon Musk is planning bigger batteries, but the economics of storing vast amounts of power to compensate for cloudy days remains daunting.

This is why combating climate change requires innovation on so many fronts. Given the enormous fixed investment and substantial R&D budgets of today’s biggest energy companies, developing technologies to use fossil fuels more cleanly remains a more likely solution.

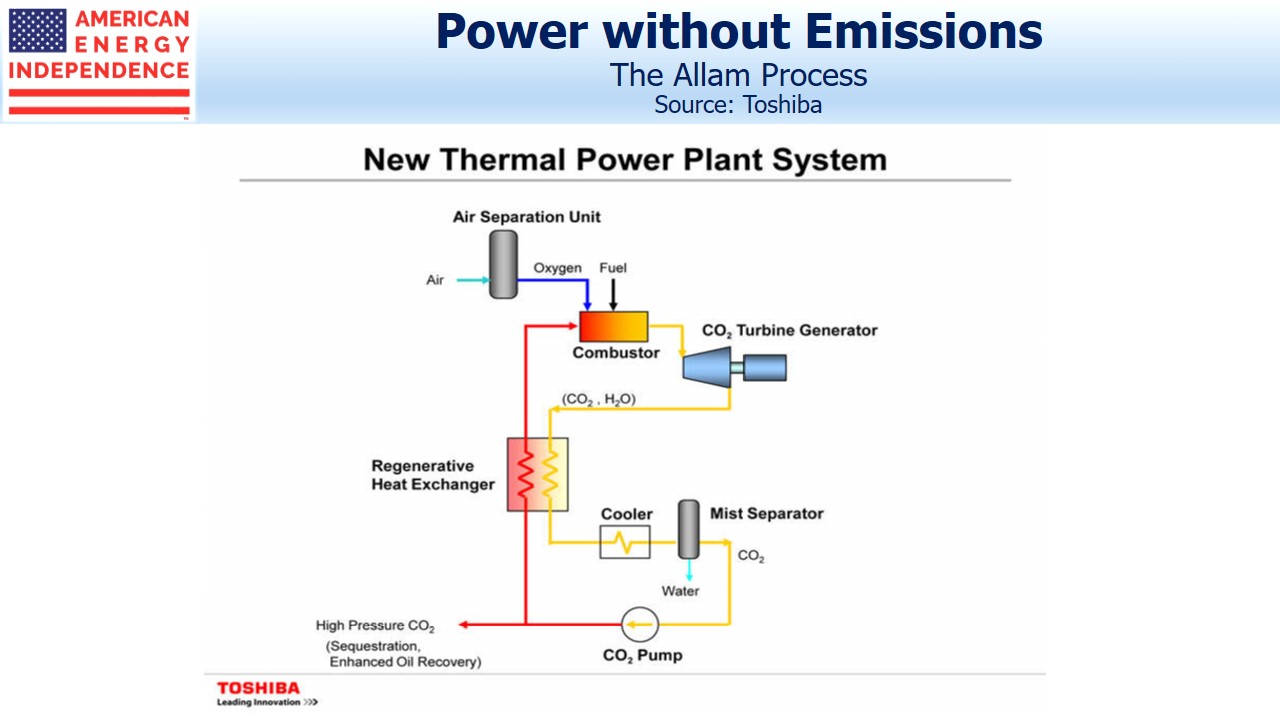

NET Power has developed a natural gas power plant that produces electricity with no CO2 emissions. Conventional single-cycle power plants burn natural gas (or coal) to heat water which acts on a turbine to generate electricity. This produces CO2, and in the case of coal plants other noxious gases and polluting particles. Combined cycle power plants use some of the produced CO2 to power a second turbine, improving efficiency but still ultimately emitting Greenhouse Gases (GHGs).

The Allam Cycle burns methane (natural gas) with pure oxygen extracted from the air (which is roughly 80% nitrogen and 20% oxygen). The result is water, and supercritical CO2 (sCO2) which is used to power the turbine. Most of the sCO2 is then recycled in a closed system to provide further power. There are no emissions, and the CO2 is eventually captured for resale or to be permanently sequestered underground.

Its backers, who include Exelon, Occidental Petroleum and venture capital firm 8 Rivers, aim to show that the technology is commercially viable. Publicly, developments have been slow. An experimental power plant is operating in La Porte, Texas. For now its power output is only being used internally while testing continues; it’s not yet reliable enough to connect to the Texas grid, run by ERCOT. NET Power expects the technology to be deployed commercially by 2022.

In testimony before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources last year, 8 Rivers principal Adam Goff noted the business potential in China and India, where local pollution is as big a concern as GHG emissions.

NET Power has been around for some time. Goff said 8 Rivers began developing the Allam Cycle in 2009. Progress has been methodical, or ponderous, depending on your perspective. Based on public comments from Goff and others, within the next year or two we should see tangible signs confirming that NET Power has a commercially viable product.

The electricity produced is expected to be cheap, partly because of the rebate from selling CO2. Occidental, one of NET Power’s investors, pumps 50 million tons of CO2 into the ground annually to boost oil production. Although the CO2 is permanently out of the atmosphere, climate extremists are unlikely to be impressed. And it’s unclear that there’s demand for the amount of CO2 that such plants would produce if the technology was widely adopted.

The Allam Cycle is not limited to natural gas. Petroleum-based products and even coal can be combined with pure oxygen to generate electricity, although the focus has been on developing the natural gas capability. Capturing the CO2 from conventional power plants is expensive because it has to be separated out from the air as it’s emitted. NET Power’s approach captures the CO2 while it’s still in a relatively pure form, which is much cheaper.

80% of the world’s primary energy comes from fossil fuels. Although only around 20% of global energy use is for electricity, that’s still substantial and initiatives to combat climate change generally contemplate increased electrification of transportation. Electric vehicles charged by hooking up to a predominantly solar and wind grid remain the dream of many. But when you consider how well fossil fuels work, and the enormous capital invested in their continued dominance, privately-owned NET Power looks like a venture that much of the energy sector is cheering on from the sidelines.

If its backers are right, they’ll earn an enormous return as well as ensuring continued demand growth for natural gas. If emission-free power from fossil fuels becomes a reality, depending on sunny and windy days supported by a huge battery back-up will seem rather quaint.