Bonds Are Dead Money

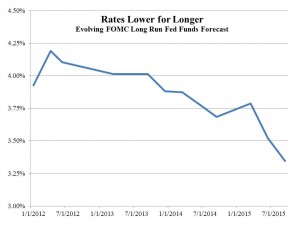

If you aspire to achieve acceptable returns from bond investments, the Fed is in no hurry to help you. They have other objectives than ensuring a preservation of purchasing power for buyers of taxable fixed income securities. Their failure to raise rates on Thursday is not that important — what’s more significant is the steadily ratcheting down of their own forecasts for the long term equilibrium Fed Funds rate.

For nearly four years the Fed has published rate forecasts from individual FOMC members (never explicitly identified) via their chart of “blue dots”. They now produce a table of values so there’s little ambiguity about its interpretation. Traders care mightily about whether they’ll hike now or in three months. It’s all CNBC can talk about. For investors, the Fed’s expectation for rates over the long run is far more interesting.

Since you might expect long run expectations about many things to shift quite slowly, by this standard the Fed’s long run forecast has plunged. The steady downward drift accelerated in recent meetings and it’s now fallen more than 0.5% since last year, to 3.35% (see chart). What this means is that their definition of the “neutral” fed Funds rate (i.e. that which is neither stimulative nor constraining to economic output) is lower. They don’t have to raise rates quite as far to get back to neutral.

Their inflation target remains at 2%, although inflation, at least as measured, is clearly not today’s problem. So the real rate (i.e. the difference between the nominal rate and inflation) has now come down to less than 1.5%. Since bond yields are in theory a reflection of the average short term rate that will prevail over the life of a bond, the Fed believes investors in investment grade debt with negligible default risk should expect this kind of real return. For a taxable investor, this will result in more or less a zero real return after taxes.

The Fed’s communication strategy has not been that helpful over the short run. Although we are provided with far more information about their thinking, it simply reveals that they don’t know much more than private sector economists and like them are always waiting for more information. The FOMC doesn’t want to provide firm guidance, since that requires a commitment which results in lost flexibility (see Advice for the Fed). The evenly split expectations for last Thursday show that forward guidance hasn’t helped traders much. But that doesn’t matter for investors; the insight into their long term thinking, presented as it is in a quantitative form, really is useful.

The Fed’s communication strategy has not been that helpful over the short run. Although we are provided with far more information about their thinking, it simply reveals that they don’t know much more than private sector economists and like them are always waiting for more information. The FOMC doesn’t want to provide firm guidance, since that requires a commitment which results in lost flexibility (see Advice for the Fed). The evenly split expectations for last Thursday show that forward guidance hasn’t helped traders much. But that doesn’t matter for investors; the insight into their long term thinking, presented as it is in a quantitative form, really is useful.

Hawkish is not an adjective that will be applied to this Fed anytime soon. In fact, one FOMC member included a forecast for a negative Fed Funds rate by year-end, a no doubt aspirational forecast but probably the first time an FOMC member has advocated such a thing. The Fed chair is clearly among ideological friends. Janet Yellen’s deeply held feelings for the unemployed inform her past writings and those of her husband George Akerlof. These are admirable personal qualities and not bad public policy concerns. Given that inflation remains below the Fed’s target, monetary policy can remain focused on doing all it can to promote growth, thus raising both employment AND inflation. Wgat some perceive as the Fed’s short run trade-off between maximizing employment and controlling inflation is unlikely to be tested anytime soon. Rates will rise slowly, because the future is always uncertain and because the neutral policy rate is in any case steadily falling towards the current one.

The low real rate contemplated by the Fed reflects their lower estimate of the economy’s growth potential. This is not a contentious view, it’s just that we’re seeing it play out through their rate forecasts.

The clear implication for bond investors though is that it’ll be a very long time before they make any money. The Barclays AGG is +0.64% YTD. This is the type of return bond investors can expect. Taxable investors are losing money in real terms and the Fed hasn’t even begun raising rates yet. Moreover, it’ll be years before this Fed gets bond yields to levels where a decent return is possible. It’s as I said two years ago in Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors. Bond holders are in for years of mediocre results or worse. It’s not going to be worth the effort. Take your money elsewhere.