Advice for the Fed

There must be more words written about the Federal Reserve and tightening of interest rates than any other issue that affects financial markets. A Google search throws up an imprecise “about 750,000” results! If each one is 250 words (less than your blogger’s typical post) that is 239 versions of the King James Version of the Bible. Although this most secular of topics is clearly not short of coverage, I’ll try and offer a different perspective.

An estimated 187 million words or so reflects the importance of a move in rates. Since the last rate hike was nine years ago, the Fed is spending much effort trying to make the eventual move anti-climactic. If their announcement is greeted with a financial yawn, that will represent a successful communication strategy. It’s not just that we’re out of practice in dealing with rising rates; it’s that the announcement and implementation both happen together. The Fed announces a hike in the Fed Funds rate, and implements it right away. The result is that we head into the day of an FOMC meeting with countless market participants and unfathomable amounts of borrowed money not knowing if their cost of borrowing overnight money will be instantly higher than it was yesterday. The uncertainty about how others will react to an immediate change in their cost of financing is why there is so much angst surrounding the “normalization” of monetary policy.

It occurred to me that the Fed could separate the two. Instead of offering various shades of certainty around when they will raise rates, why not say that any hike will take effect with a three month delay? Term money market rates would immediately adjust, but if the Fed announced a hike with effect at a certain future date the knowledge of higher financing would not coincide with the actual impact on financing over three months and less. Trading strategies that rely on a certain level of financing will have some time to adjust. Market participants will know for certain that rates will be higher in three months’ time, as opposed to having to make informed judgments based on public statements and economic data. And while the clear expectation will be that the pre-announced tightening will take place on schedule, the Fed does retain the flexibility to undo it in extraordinary circumstances. It would take some of the guesswork out of getting the timing right.

It’s seems such a simple fix to the problem. I haven’t read all of the 750,000 Google results to see if they include this suggestion, but I’ve never seen it myself. Maybe someone at the Fed will read this. They may conclude it’s worth what they paid for it, like any free advice. We’ll see.

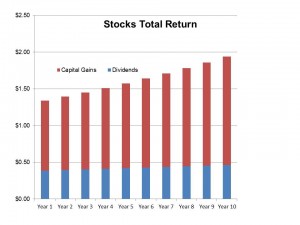

ed while stock dividends grow. The S&P500 currently yields around 2%. Historically, dividends have grown at around 5% annually. So if you invested $100 in stocks today you’d receive a $2 dividend after the first year but if past dividend growth of 5% annually continued, in ten years your $2 dividend would have grown to $3.26. Put another way, if dividend yields are still 2% in ten years time, your $100 will have grown to $162.89 (that’s the price at which a $3.26 dividend yields 2%). Since returns on stocks come from dividends plus their growth, a 2% dividend plus 5% growth equals a 7% return. Naturally, the two imponderables are (1) will dividends grow at 5%, and (2) will stocks yield 2% in 10 years (or put another way, where will stocks be?). These are the not unreasonable questions of the bond investor as he contemplates a larger holding of risky stocks in place of bonds with their confiscatory interest rates.

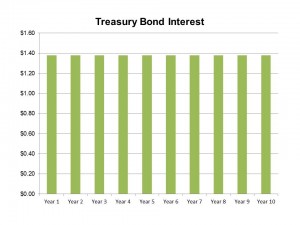

ed while stock dividends grow. The S&P500 currently yields around 2%. Historically, dividends have grown at around 5% annually. So if you invested $100 in stocks today you’d receive a $2 dividend after the first year but if past dividend growth of 5% annually continued, in ten years your $2 dividend would have grown to $3.26. Put another way, if dividend yields are still 2% in ten years time, your $100 will have grown to $162.89 (that’s the price at which a $3.26 dividend yields 2%). Since returns on stocks come from dividends plus their growth, a 2% dividend plus 5% growth equals a 7% return. Naturally, the two imponderables are (1) will dividends grow at 5%, and (2) will stocks yield 2% in 10 years (or put another way, where will stocks be?). These are the not unreasonable questions of the bond investor as he contemplates a larger holding of risky stocks in place of bonds with their confiscatory interest rates. xes, around $0.38. This assumes the Federal dividend tax rate and the ObamaCare surcharge but excludes state taxes.

xes, around $0.38. This assumes the Federal dividend tax rate and the ObamaCare surcharge but excludes state taxes.