The Bond Market Loses Its Friends

In 2013, my book Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors presented a populist framework for evaluating interest rates. The prospects for the bond market can only be evaluated by considering the U.S. fiscal situation, which is steadily deteriorating along with that of many states. I was dismayed to read the other day of an analysis that places New Jersey (where I live) dead last behind even Illinois in its funding of public sector pensions. We have, at almost every level of government and household, too much debt.

The solution has, since the 2008 Financial Crisis been low rates. If you owe a lot of money low rates are better than high ones. Financial repression in the form of returns that fail to beat inflation after taxes is a stealth means of transferring wealth from savers (lenders) to borrowers. Count the central banks of China and Japan with their >$1TN in U.S. treasury holdings among those on the wrong side of this trade, along with many other foreign governments and sovereign wealth funds.

Some have argued that low rates only help the wealthy (through driving up asset prices); they impede lending (because lending rates aren’t high enough to induce banks to take risk); they force savers to save more (thereby consuming less) than they otherwise would, because returns are so low; and they communicate central bank concern about future economic prospects. Low mortgage rates help homeowners and drive up home values which helps McMansion owners but not first-time buyers. Low rates may be good for the wealthy, and by lessening the burden of the government’s debt they may indirectly help everyone. But to someone with little or no savings, the tangible benefits are not obvious even if they are real (through higher employment, for example).

Nonetheless, we are likely at the early stages of watching this benign process swing into reverse. The conventional result of lower taxes combined with higher spending should be a wider deficit, rising inflation and therefore higher interest rates. The bond market is already beginning to price this in through higher yields, well before any discussions of next year’s budget (or even the appointment of a White House Budget Director).

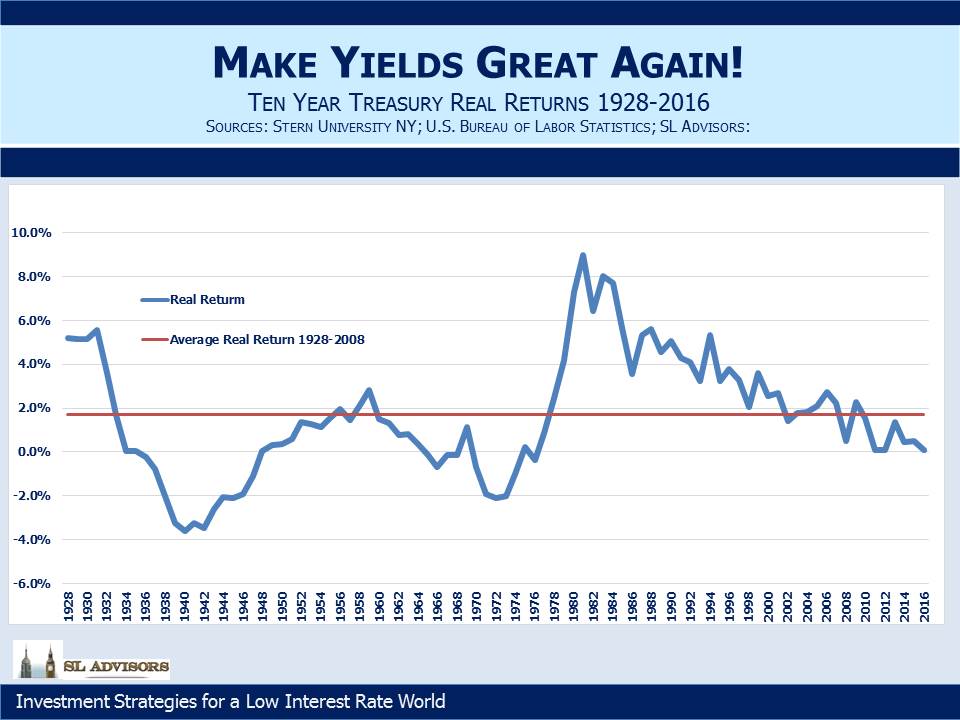

Part of the problem is that bonds don’t offer much value to begin with. They’ve represented an over-priced asset class for years, and it’ll take more than a 0.50% jump in yields to fix that. From 1928 until 2008 when the Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing program began distorting yields, the average annual return over inflation (that is, the real return) on ten year treasuries was 1.7%. This is calculated by comparing the average yield each year with the inflation rate that prevailed over the subsequent decade-long holding period of that security. So investing in a ten year treasury note today at 2% would, if the Fed hits its inflation target of 2% over the next ten years, deliver a 0% real return (worse after taxes).

Given the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target, even a 4% ten year treasury (roughly double its current yield) would appear to represent a no better than neutral valuation. The deficit was already set to begin rising again before even considering any Republican-enacted tax cuts and other stimulus (such as infrastructure spending). In fact, borrowing at today’s low rates to invest in projects that will improve productivity makes sense in many cases. But under such circumstances, with the possibility of inflation above 2%, perhaps a yield of 5% or even 6% is the threshold at which ten year treasuries (and by extension other long term U.S. corporate bonds at an appropriate spread higher) could justify an investment.

Holding out for such a yield is fanciful. Millions of investors demand far less, which is why we don’t bother with the bond market. Our valuation requirements render us wholly uncompetitive buyers.

Low rates may be the best policy for America, but it looks as if we’re about to try boosting growth through greater fiscal stimulus. The Federal Reserve will seek to normalize short term rates, perhaps faster than their current practice of annual 0.25% hikes. The twin friends of gridlock-induced fiscal discipline (sort of) and low rates are moving on, leaving fixed income investors to fend for themselves. Bonds are a very long way from representing an attractive investment.