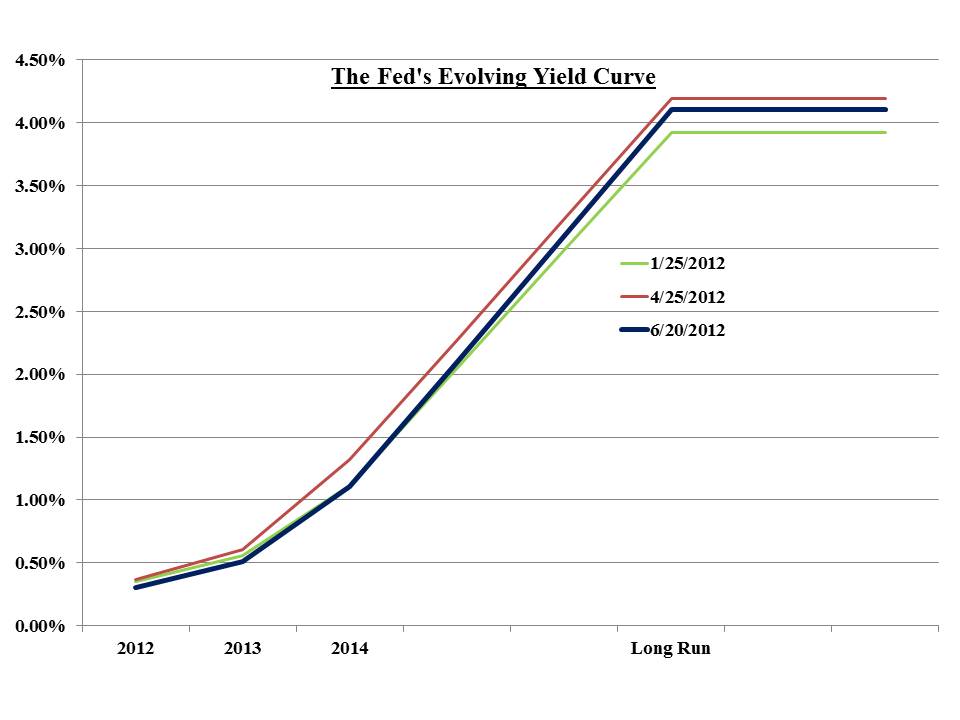

The Fed's Evolving Yield Curve

On Wednesday the Federal Reserve released their third set of detailed interest rate forecasts this year. Following Ben Bernanke’s philosophy of open communication, the FOMC publishes forecasts for short term rates from each voting member. While they don’t link a name with each number, you can see what members expect short term rates will be at the end of this year, 2013, 2014 and over the long run (whose start is not defined).

In effect you can construct a crude yield curve incorporating their collective outlook. Comparing their yield curve with the market is fascinating, although market yields and implied rate forecasts have been steadily diverging from those issued by the Fed. In fact, the Fed’s own forecast has been remarkably stable even while ten year treasury yields have traversed a 1% range reaching 2.5% before falling recently to 1.5%. The chart below is derived from the average of all FOMC member’s rate forecasts at year-end. So there’s a clear discrepancy between the Fed’s statement that short term rates will remain low through the end of 2014 and the six FOMC members who expect rates to be higher (three of whom target hikes as soon as next year). At the same time that the Fed extended Operation Twist to the end of this year, they reaffirmed that the long run equilibrium short term rate is around 4%. Long term bonds continue to trade at yields that defy that forecast. The Long Run is still some ways off, but today’s bond buyers are fairly warned.

There is growing evidence that the “Fiscal Cliff”, looming in January 2013, will take a toll on the economy before its arrival. Although reports suggest that both parties are discussing a resolution to the sudden tax hikes and spending cuts that will take place under current law on January 1st next year, there’s little tangible evidence of such. There is growing evidence that companies are managing their businesses by incorporating this uncertainty into today’s spending decisions. It occurs to me that, while most economic forecasts project a substantial (3%+) GDP hit in 1Q13 IF no action is taken, few have considered that waiting until December’s lame-duck session of Congress to do the inevitable is quite likely to depress growth in the meantime. The non-partisan view surely blames both sides for placing the purity of their own political beliefs ahead of the pragmatism of removing at least one element of uncertainty.

The comments from many Congressmen that the planned tax hikes and spending cuts will assuredly be rolled back would be more credible if they didn’t insist on waiting until the last possible moment do do so.

For our part, we remain generally fully invested across our strategies. Owning steady, dividend paying stocks combined with a beta neutral hedge provides an uncorrelated source of return while markets are being buffeted around. Our most recent decisions have been to exit the last remaining shares of Family Dollar (FDO) which no longer provides compelling value given its recent increase in price. We have added modestly to Coeur d’Alene (CDE) which recently announced a share buyback given the large discount of its stock price to the estimated net asset value of its gold and silver reserves.

We have largely exited the short Euro position which has been held in our Fixed Income strategy as useful protection for the holdings of bank debt (given their equity sensitivity). It worked well for quite a while, but a few weeks ago I heard a reporter from the New York Times confidently announce on a radio interview that the Euro was going down and Greece would soon exit. Short Euro is probably too widely held, and isn’t that interesting any more.

Disclosure: Author is Long CDE