Fiscal Cliff – Alternatives to Conventional Wisdom

While various ideas are floated and journalists report on the state of negotiations, the market consensus seems to be settling on the idea that Congress and the White House will do enough to avoid the automatic tax hikes and sequestration that will follow if they fail to agree. The bounce in the S&P500 (SPY) over the past couple of weeks presumably reflects this conclusion. As well it should, for both sides will struggle to show any political gain out of imposing enough fiscal drag to cause a recession early next year. The negotiations will probably not be easy and key concessions ought to be expected at the end rather than the beginning. But an agreement of some sort is probably what we’ll get – some tax hikes on the wealthy, a few spending cuts and a solemn promise to do more next year.

This got me thinking about alternative scenarios. Most obviously, there could be no agreement. The talks could break up in acrimony as one or both sides conclude that shared responsibility for a recession is preferable to making big concessions on core parts of their platform. For Republicans this is Taxes, and for Democrats it’s Entitlements. It’s not made easier by opinion polls that show quite clearly what people want – fiscal discipline without cuts in Entitlements or broad tax increases. The fiscal discipline that would therefore be imposed automatically through a failure to agree could cause a GDP contraction of 3% or more and is unlikely to be greeted warmly by stocks.

Another possibility is negotiators go farther than expected. Somehow they reach a grand compromise, embracing part of Simpson-Bowles and reining in entitlements while simultaneously raising taxes. It’s of course not likely, but if it did happen this “good news” would likely cause greater fiscal drag than a more modest negotiated agreement. Indeed, it’s hard to see how you can reduce the ongoing fiscal stimulus that profligacy creates without some fiscal drag as a result. But in this case interest rates, which in the past have softened the blow of such events by falling, wouldn’t be much help. Bond yields scarcely reflect any concern about the long term budget outlook – or if they do such concern has been effectively silenced by the Fed’s QE (1,2,3 etc). So the economy would endure the pain of newfound fiscal discipline without the salve of lower bond yields. This is also unlikely to be a good outcome for the market, in spite of the hand-wringing over business as usual.

So the more a modest negotiated settlement is expected by market participants, the less attractive the alternative outcomes appear.

We are holding around 10% cash in our Deep Value Equity Strategy, and currently think we have less than 90% of the short term volatility of the market since many of the names we own are fairly stable businesses. Many companies are issuing cautious guidance and so the bottom-up view has started to reflect some of the macro concerns many investors have felt for a long time. Among the names we do own Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B) is one of our bigger holdings. It’s trading close to 10% above book value, the upper boundary at which the company has indicated it will buy back shares. We recently added to McDonalds (MCD) on weakness since high single digits EPS growth and a P/E of 16 are a reasonable level at which to invest.

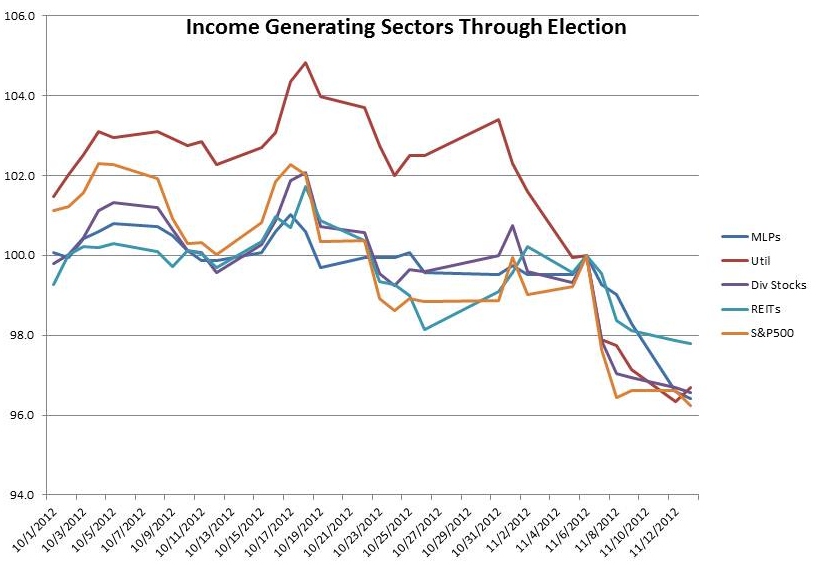

We’ve also added to Master Limited Partnership which had sold off along with other income generating sectors such as high dividend stocks and utilities. MLPs after tax returns may be even more attractive compared with traditional income generating sectors of the equity market depending on what Congress does to taxes on investment income.