Valuing Kinder Morgan in its New Structure

The Kinder Morgan transaction announced Sunday night represents a new paradigm for Master Limited Partnership (MLP) investors. Like any new paradigm, digesting its impact takes some time. Rich Kinder, CEO and largest owner of the eponymous firm that controls Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP) and El Paso (EPB) was one of the early users of the MLP model. He recognized the power of the partial tax shield the structure provides its investors to lower his cost of capital, thereby supporting a growth strategy as this funding advantage allowed the accumulation of additional assets.

MLPs are liked for their steady, tax-deferred yields. The consequent K-1s are generally worth it for investors with $500K or more to allocate. Low turnover is key, because selling an MLP invariably results in the recapture of taxes previously deferred. In our view this directs the investor towards MLPs with stable, predictably growing cashflows. A strategy that involves regular switching out of “rich” names and into “cheaper” ones can create tax consequences that swamp any perceived positive impact on the portfolio. If your money manager is personally invested in the same securities that his clients own, you’ll find he’s acutely sensitive to after-tax returns and as a result is a miserly user of brokers while letting the tax advantages compound over time.

While stable, tax-deferred returns are a well known feature of MLPs, an element that receives far less attention is the weak governance rights and preferential position of the General Partner (GP). Although MLPs are publicly traded, unitholders (as MLP investors are known) have very limited rights compared with traditional investors in corporate equities. Not all MLPs have a GP, but those that do place most of the power with the GP. Read through the prospectus of a typical MLP and you’ll find out just how hard it is to fire a GP. That’s why you don’t see activists buying MLPs. Unitholders don’t get much say in its operation.

Meanwhile, the GP is entitled to a split of the Distributable Cashflow (DCF), basically defined as earnings plus depletion and depreciation less maintenance capex (the cost of keeping existing assets in good working order). The 50% share of DCF that most GPs enjoy represents a significant drag on returns that unitholders get. In the case of KMP, it had long been understood that this limited their ability to grow, and consequently KMP’s distribution yield was around 6.8% prior to this transaction, 1-2% above its peers. Because MLPs don’t retain earnings, they have to raise additional capital by issuing debt and equity for each new capital investment. KMP’s high yield plus the Incentive Distribution Rights (IDR) drag to which its GP KMI was entitled was making it hard to find projects that would cover its cost of capital. KMP was too big to make investments that could cover its funding cost and drive growth. In addition, the 50% GP share continues as cashflows grow while the GP doesn’t have to fund the capital required to grow those cashflows. Just as a hedge fund manager’s 1.5% management fee assures that asset growth is profitable, so it is for the MLP GP.

Rich Kinder complained that the market wasn’t fully valuing KMP’s opportunities, but the price stayed stubbornly low. Given Kinder’s bullish view of M&A activity in the energy infrastructure space, his inability to participate with an expensive currency was frustrating. He concluded that, as good as the MLP structure is, there were limits and the growth of the Kinder enterprise was testing those limits.

Some years ago we began shifting our MLP strategy away from GP-controlled MLPs and into the GPs themselves (as more became publicly available) as well as into MLPs who have no GP (some have bought the GP back in, simplifying their structure and eliminating the drag of IDRs which makes them more competitive acquirers). So although we did once own KMP, we shifted into KMI. We gave up the tax deferral since KMI is a C-corp, paying corporate income tax like any other U.S. corporation and providing investors with a 1099 rather than a K-1. We felt sharing in the 50% IDR split of KMP’s DCF was preferable to having to pay it away as a KMP unitholder. As we’ve written before, it’s analogous to investing in the hedge fund manager (for whom asset growth is always positive) rather than the hedge fund (for whom asset growth may or may not be good). The fact that Rich Kinder concentrated his ownership in KMI rather than KMP was an additional factor we considered.

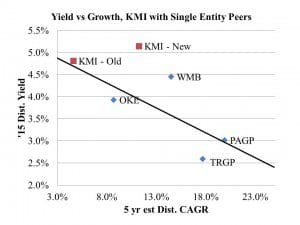

Now that KMI has simplified its structure, e liminated its IDR and cleverly created $20BN of tax savings, it has a higher dividend with better growth prospects than before. Conventional valuation of KMI compares it with other C-corps that own their GP and have an MLP underneath on which they rely to fund capital investments and funnel cashflows back up to the GP. KMI’s peer group in this regard includes Oneok Inc (OKE), Williams Companies (WMB), Targa Resources Corp (TRGP) and Plains GP Holdings (PAGP). Generally, faster growth prospects (defined here as 5 year estimated Distribution Compounded Annual Growth Rate) dictate a lower yield, and so the chart to the left illustrates where these securities lie. KMI-Old (i.e. before the announcement) was on a regression line linking its peers, but we liked it because we felt there was the possibility of a transformational transaction such as the one we’ve just seen, KMI-New appears to be a relatively more attractive security because its better growth prospects don’t appear to be fully reflected in its yield. If KMI’s yield dropped down to the regression line its price would be around $50 versus its current level of $39.50 (we’ve assumed they buy back the outstanding warrants at current prices and adjusted their sharecount accordingly). So we still own KMI.

liminated its IDR and cleverly created $20BN of tax savings, it has a higher dividend with better growth prospects than before. Conventional valuation of KMI compares it with other C-corps that own their GP and have an MLP underneath on which they rely to fund capital investments and funnel cashflows back up to the GP. KMI’s peer group in this regard includes Oneok Inc (OKE), Williams Companies (WMB), Targa Resources Corp (TRGP) and Plains GP Holdings (PAGP). Generally, faster growth prospects (defined here as 5 year estimated Distribution Compounded Annual Growth Rate) dictate a lower yield, and so the chart to the left illustrates where these securities lie. KMI-Old (i.e. before the announcement) was on a regression line linking its peers, but we liked it because we felt there was the possibility of a transformational transaction such as the one we’ve just seen, KMI-New appears to be a relatively more attractive security because its better growth prospects don’t appear to be fully reflected in its yield. If KMI’s yield dropped down to the regression line its price would be around $50 versus its current level of $39.50 (we’ve assumed they buy back the outstanding warrants at current prices and adjusted their sharecount accordingly). So we still own KMI.

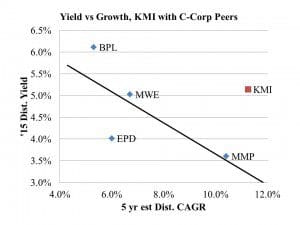

But here’s the point. There’s a good case that KMI should no longer be compared with the other C-corps (technically, PAGP is a partnership but for tax purposes they issue a 1099). What they all have in common is an entity that controls the GP to a publicly traded MLP. This used to apply to KMI but once t heir simplifying transaction closes later this year that will no longer be the case. KMI will actually look more like a different peer group, consisting of MLPs that no longer have a GP. This peer group includes Buckeye Partners (BPL), Enterprise Products Partners (EPD), Markwest Energy Partners (MWE) and Magellan Midstream Partners (MMP). The revised Yield vs Growth chart comparing KMI with this new peer group is on the right. If KMI was on the new regression line its price would be around $61.

heir simplifying transaction closes later this year that will no longer be the case. KMI will actually look more like a different peer group, consisting of MLPs that no longer have a GP. This peer group includes Buckeye Partners (BPL), Enterprise Products Partners (EPD), Markwest Energy Partners (MWE) and Magellan Midstream Partners (MMP). The revised Yield vs Growth chart comparing KMI with this new peer group is on the right. If KMI was on the new regression line its price would be around $61.

None of these firms is a perfect comparison. BPL’s yield remains high because of challenges to its tarrifs in the NY area as well as its recent mis-step in Merchant Services. EPD has an exceptionally well regarded management team which depresses its yield. Markwest has more cashflow variability because of its gathering and processing business. Nonetheless, the fair value yield for KMI on this basis is even lower than using the more conventional method. We believe it’s warranted due to a now more competitive cost of capital with which to fund acquisitions.

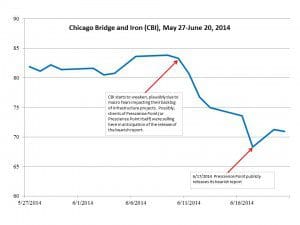

KMI has been a long term holding of ours. We used the weakness caused by Hedgeye’s negative report last year to add. We continue to think it represents an attractive investment, and believe the announced restructuring has made it substantially more attractive than is currently reflected in its market price.