Targa Resources Needs an Activist

Writing a blog from the vantage point of your own firm is fantastically liberating compared with analyzing markets at a well-known behemoth, where any criticism risks offending a corporate client. Thus it was that in April 2014 I could write ADT and the Ham Sandwich Test, as we invoked Warren Buffett’s advice to only invest in companies with a sufficiently strong business model that they could be run by a ham sandwich. In other words, management can surprise you with their ineptitude. ADT continues to disappoint.

Sometimes the failings of management are rather more subtle. The “Peter Principle” holds that managers rise to the level of their incompetence, to the detriment of shareholders. Success in one position leads to promotion further up the corporate ladder until the demands of the role exceed the manager’s abilities, at which point he stops moving up. Too often, Boards of Directors stumble in their oversight and allows the management to engage in self-interested behavior This is what has happened at Targa Resources Corp (TRGP) which is the General Partner (GP) of Targa Resources Partners (NGLS). NGLS is an energy infrastructure business structured as a Master Limited Partnership (MLP). They run pipelines for Gathering and Processing (G&P) crude oil and natural gas, and provide additional “downstream” services such as fractionation, storage, distribution and marketing.

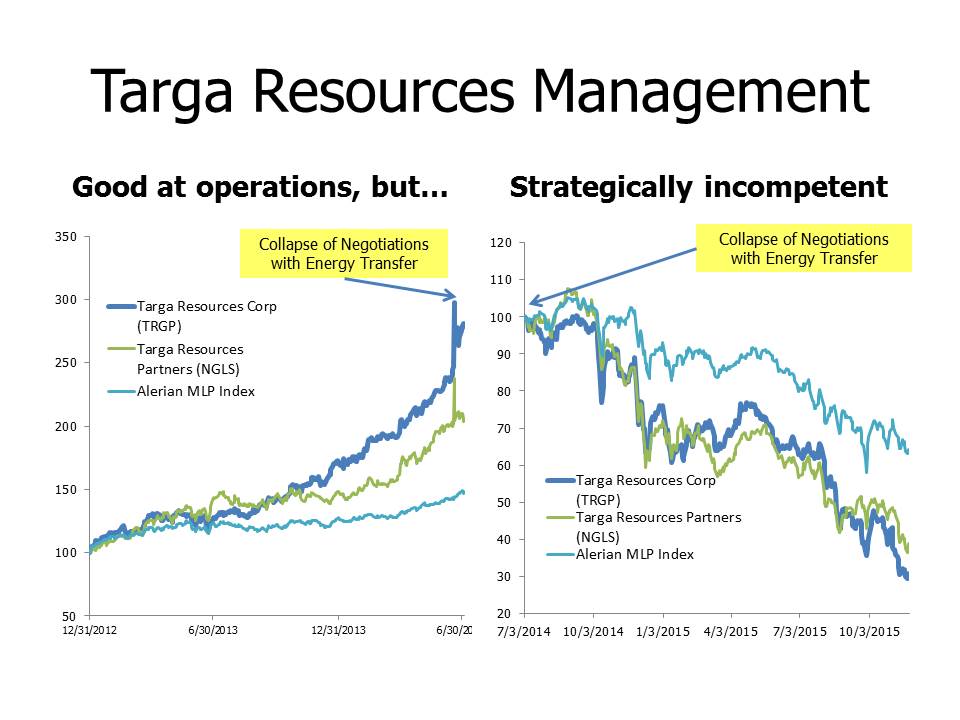

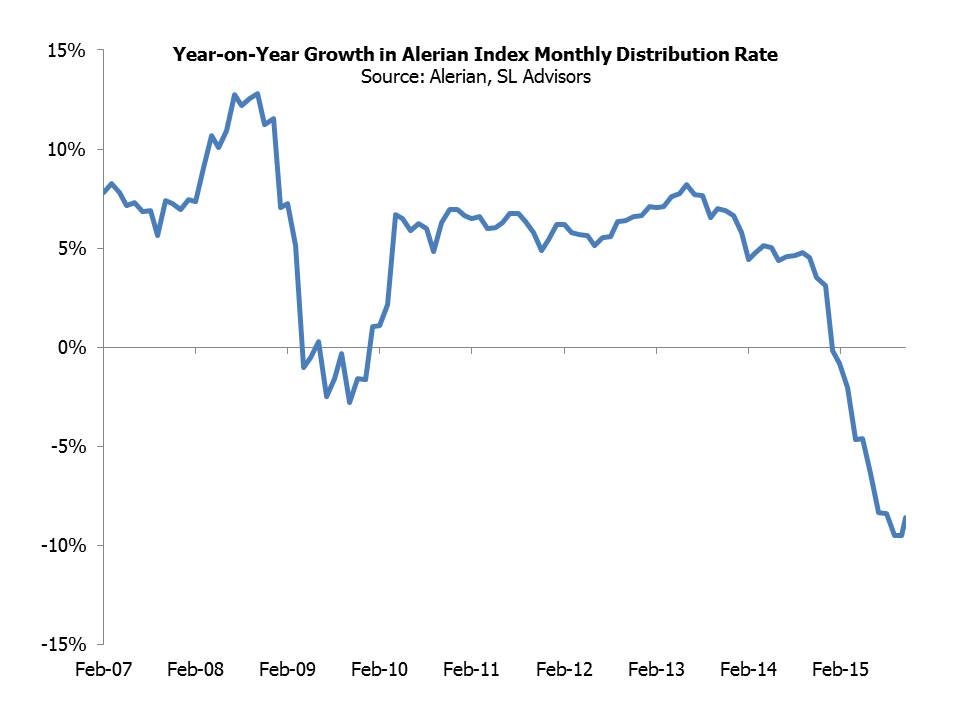

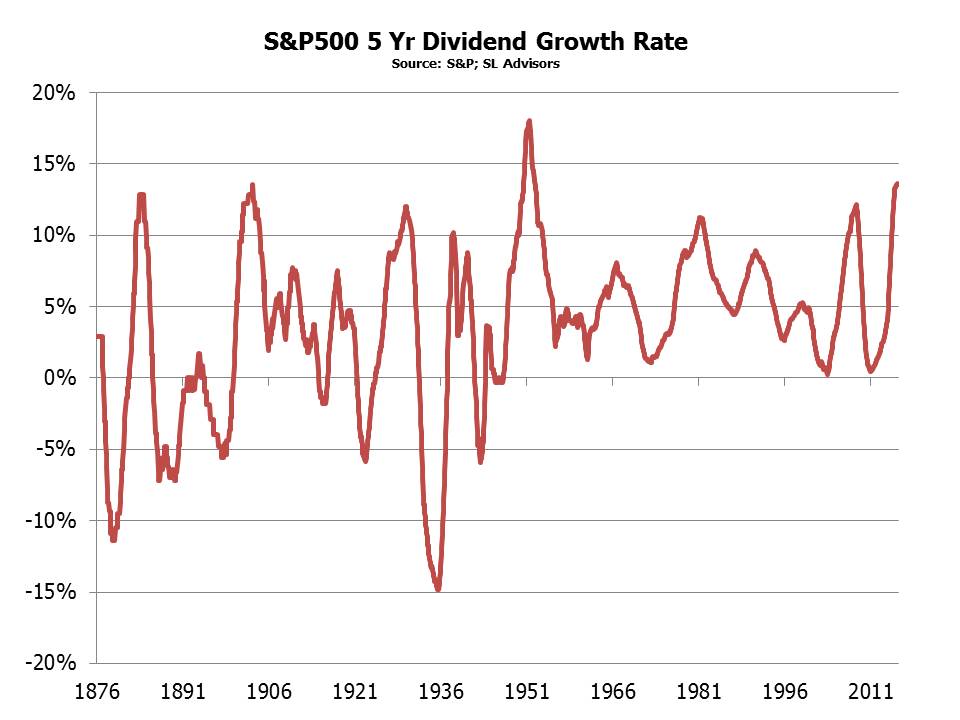

The business has been ably run by its GP, led by Joe Bob Perkins. Distributions since 2008 have grown annually at 8.5%. Even in 2015, with distributions on the Alerian Index down 6% compared with last year (see Measuring Dividend Growth is Complicated), NGLS has managed 6.2% growth. TRGP’s 2015 distributions are up 26.5% compared with 2014. That’s why you own the MLP GP rather than the MLP itself, because they grow faster and it’s where the people that actually run MLPs put their own money (see Follow the MLP Money).

However, TRGP’s operating excellence has not been matched by its strategic insight. Management has run the business well and at the same time destroyed substantial wealth for their investors, via a Board rubberstamping management’s self-serving recommendations. We need Joe Bob Perkins and his team to focus on operations and let someone more capable lead the company. July 2014 was the point at which the strategic inadequacy of TRGP’s leadership began to weigh on their strong operating ability. That was when the market’s growing recognition of their value was highlighted with Energy Transfer Equity (ETE)’s attempt to acquire them. CEO Kelcy Warren is someone who clearly understands the value of the MLP GP (see Energy Transfer’s Kelcy Warren Thinks Like a Hedge Fund Manager). Although it’s breathtaking to consider today, with TRGP languishing at $41,in July 2014 negotiations broke down with TRGP trading as high as $160. In other words, Perkins and his Board were unwilling to sell their 42.4M outstanding shares of TRGP, citing undervaluation at that price.

TRGP remained bullish on the outlook for gathering and processing, because in October 2014 they announced the acquisition of Atlas Pipeline Partners (APL) by NGLS, with TRGP acquiring APL’s GP and related assets at Atlas Energy, LP. They paid with $610M of cash (financed with debt) and 10.4M shares of TRGP stock, (then worth $1.1B trading at an adjusted close of $104 on the day of the announcement, even though by that point it had shed a third of its value since the aborted discussions with ETE). Although they weren’t willing to sell at $160 in July 2014 to a primarily long haul pipeline company, three months later they were willing to trade their stock while taking on leverage (previously there was almost no leverage at TRGP) for a business with significantly more commodity exposure (APL’s G&P business is closer to the well-head with significantly less fixed fee contracts). In addition, they conceded $78M in GP/IDR givebacks at TRGP while paying $190M in change of control and transaction fees as part of the Atlas transaction.

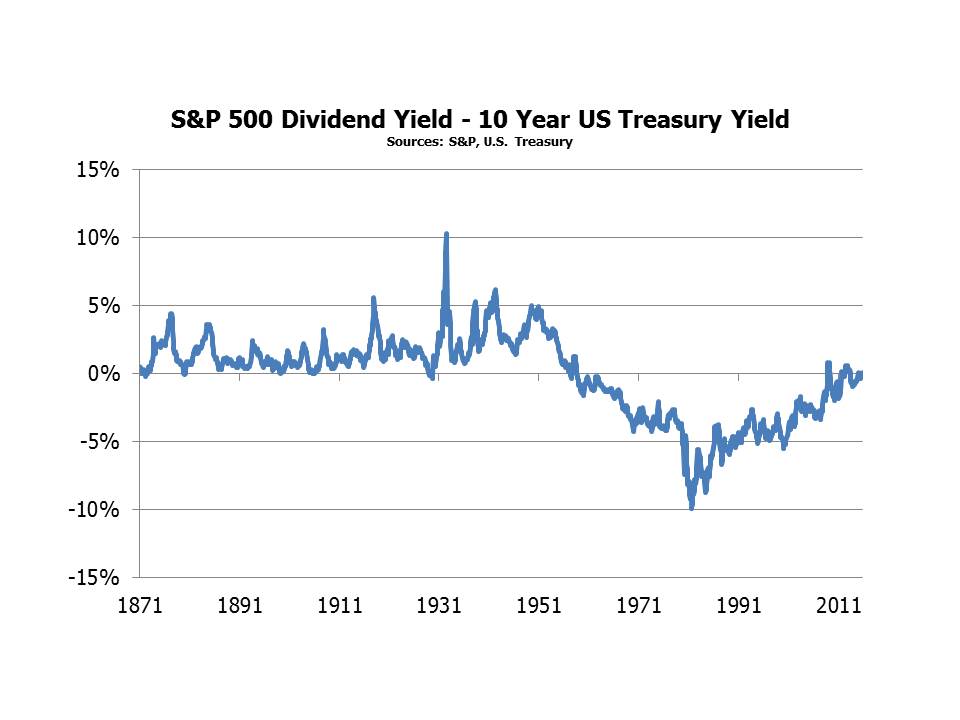

In 2015 TRGP and NGLS stock fell along with the rest of the MLP sector, although their operating performance remained fine. Then on November 3rd, management stunned investors by announcing that TRGP would acquire NGLS by issuing new shares to current NGLS owners. TRGP was at $58 the day before the announcement, and since then has sunk below $40 to complete a colossal destruction of value. Just prior to the announcement, TRGP was yielding 6.95% and NGLS 10.8%. The high yield on NGLS reflected a higher cost of equity, threatening to impede its ability to fund its growth by issuing new equity at a competitive cost. The logic behind the merger was to improve the distribution coverage by giving NGLS unitholders lower-yielding TRGP stock, and to improve the growth outlook by eliminating the payments to TRGP that take place under Incentive Distribution Rights as with most MLP GPs.

Investors in TRGP regarded the elimination of the economic and other associated rights of the GP negatively. TRGP always has the option to temporarily waive its claim to IDRs if it supports NGLS (as it did in the Atlas transaction), so why concede them permanently? Consequently, TRGP’s stock sank. But it was no better for NGLS unitholders. The pricing of 0.62 shares of TRGP for each unit of NGLS was expected to represent an 18% premium to the prior day’s close, but as TRGP investors reacted poorly to the loss of their GP rights the takeover premium quickly evaporated. On top of this, the transaction is taxable to NGLS unitholders.

Rather than lowering its cost of capital, TRGP management has managed to increase it. TRGP’s yield has jumped from 6.25% to 8.75%. Once again, the investment bankers advising an MLP have wrought mayhem (see Investment Bankers Are Not Helping MLPs). TRGP’s management has completed their 180 degree U-turn, from rejecting ETE’s overtures in 2014 when their stock was at $160 to now issuing a substantial number of new shares with the price 75% lower.

It represents strategic incompetence of Biblical proportions.

Given the reaction of TRGP and NGLS, everybody is poorer. Leon Cooperman dryly asked whether their advisors had expected such a market reaction on the conference call to discuss the transaction. It still has to be approved by both sets of shareholders. Given the series of mis-steps by this leadership team and the destruction of value they have perpetrated, it’s not clear why anyone would vote to approve. Joe Bob Perkins and his strategy team have clearly risen to the level of their incompetence. They should stick to running the day-to-day business and stay away from strategy because they are so bad at it. TRGP is desperately in need of new leadership, of interest from activist shareholders who will demand a more thoughtful approach. We plan to vote against the proposed transaction, and we believe all TRGP and NGLS investors would benefit from voting No.

We continue to hold TRGP as we believe the assets which have G&P exposure to the best basins and enviable downstream NGL logistics have strategic value to many midstream peers, and are worth substantially more in others’ hands. We encourage the Board to consider their fiduciary duty to shareholders and act in their best interests by pursuing a sale of the company.

We are also invested in ETE.

.

.