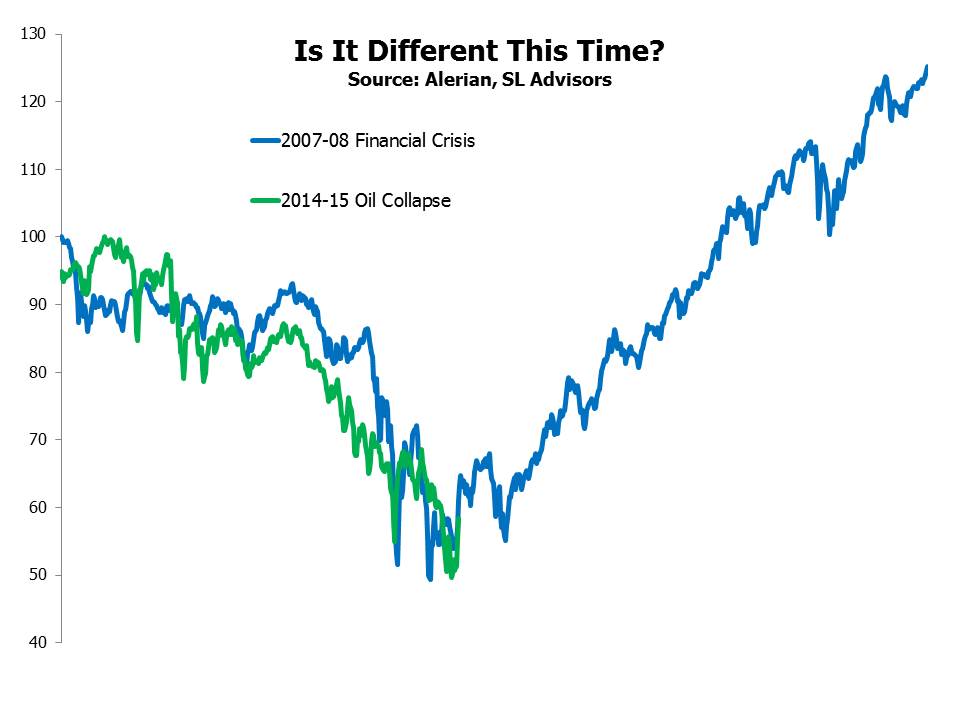

The 32.6% collapse in MLPs was in many ways worse than the 2008 financial crisis. Although not as bad as 2008 when MLPs lost 36.9%, almost every asset class was down that year so there was little unique about MLP performance. In 2015 MLPs endured their own, private performance disaster. The Energy sector was in the background singing a similar tune, but midstream energy infrastructure with its reliably boring toll model behaved like a group of highly-leveraged, high-cost oil drilling businesses, sucking investor positions seemingly into a black hole. Like most MLP investors, we didn’t see it coming. A forest from the trees problem due to being too close. We’re going to offer our perspective on how we got here and what it means for future returns.

How We Got Here

First, a little bit of history. The Master Limited Partnership (MLP) legal structure was enshrined in the 1986 Tax Reform Act signed by President Reagan. Provisions to this law passed by Congress in 1987 limited the use of the MLP structure to natural resource activities. Through subsequent IRS rulings this has evolved to mean anything to do with oil, natural gas, natural gas liquids and coal all along the value chain from extraction to distribution.

The exemption from corporate income tax represents the main and significant advantage of the MLP for equity owners. The familiar “double taxation” of corporate profits via corporate income tax followed by dividends or capital gains tax to the equity holder is avoided with MLPs, since they are “pass-through” vehicles. Their profits are only taxed once, at the equity holder’s level. Because more of the profits from an asset go to the owner, MLPs are a good legal structure within which to hold eligible assets. However, because the MLP itself doesn’t pay tax, the tax code ensures that the owners of the MLP most assuredly do.

The structure is most suitable for U.S. High Net Worth (HNW) investors. MLP tax reporting, as with limited partnerships in general, uses a K-1 form rather than the simpler 1099. Few people who file their own tax returns without the help of an accountant will tolerate this. Many accountants guide their clients away from K-1s although in my experience it’s because they find them tiresome and disregard the economic benefits to their clients.

Most of the money invested in U.S. public equities that might consider MLP equity securities isn’t subject to U.S. taxes, either because it’s tax-exempt (such as pensions, endowments and foundations) or because it’s non-U.S. (sometimes subject to dividend taxes; specific tax treatment isn’t important for our purposes). U.S. tax-exempt investors who choose to hold MLPs can be liable for UBIT (Unincorporated Business Income Tax) which they usually reject because they don’t wish to file a tax return. Non-U.S. investors can be subject to Effectively Connected Income Tax (ECI), which can reach Draconian levels and effectively eliminates their MLP appetite. Taxable corporations (such as insurance companies) can hold MLPs so the investor base isn’t limited to U.S. HNW investors. However, expanding the universe of MLP investors beyond its traditional base is not easy, and this remains an important consideration as we learned in 2015.

My first involvement in MLPs was back in 2005, when at JPMorgan we seeded Alerian Capital Management’s offshore hedge fund. Gabriel “Gabe” Hammond, Alerian’s founder, launched the Alerian Index with his partner Kenny Feng (now Alerian’s CEO). Because the K-1 tax reporting was unpalatable to millions of smaller U.S. retail investors much effort was expended with tax accountants in search of the holy grail, which was a tax-efficient way to allow MLP investors to receive a 1099. Solving this problem would open up an entirely new investor class to MLPs. The payoff was potentially huge. Many different structures and solutions were considered. It just wasn’t possible.

However, the absence of a tax-efficient way to give MLP investors 1099s didn’t remain a hurdle for long. Within a few years mutual funds and exchange traded funds appeared which were structured as C-corp ’40 Act funds[1]. They invested in MLPs, delivered 1099s to their investors and paid 35% corporate income tax on the returns. There was no tax-efficient way to avoid the K-1, so it was done in a decidedly tax-inefficient way. To this day, most of the mutual funds and ETFs that focus on MLPs are taxed as corporations, although a few are highly tax efficient RIC-compliant structure such as ours that limit their MLP investments to 25% of the fund. Investors are amazingly oblivious to this, in part because it doesn’t reduce the stated yield but rather comes out of the fund’s Net Asset Value. Although the taxes show up in the form of eye-popping expense ratios of as much as 9%, few retail investors or their financial advisors are aware of this. Even worse, those that do have knowledge of this substantial burden operate under the belief that the tax component is somehow not real. Maybe an expense ratio this high looks like a mistake. Who could possibly design such a thing? These funds carefully avoid stating that achieving the return on the Alerian Index is their objective, because it is of course unattainable and their historic returns show this. The sequential thought process through 2013 was (1) MLPs have done well (2) I don’t want K-1s (3) Here’s a vehicle that gives me MLPs without K-1s. Fund inflows boomed.

Many things are clear in hindsight. One of them is that much of the new money entering the MLP sector via very tax-inefficient funds didn’t possess the same understanding of what they were buying as the HNW investor. They hadn’t examined underlying holdings or thought much about future prospects. Recent positive returns were their investment thesis. Consequently, just as rising prices drew them in, falling prices have seen them flee.

The HNW investor was attracted by stable distributions that were largely tax-deferred (another benefit of investing directly in MLPs) with modest growth. Such investors don’t trade their positions, because to do so would undo the tax deferral benefits. As a result, MLPs enjoy far more stable ownership than most public companies, just the sort of long term outlook many commentators despair is absent from today’s capital markets. Midstream businesses are steady, fee-generating sources of income and they attracted appropriate long-term investors not looking for excitement or high growth. As long as MLPs paid their distributions things were fine.

Dividends are an inefficient way for corporations to return money to shareholders because they create a quarterly tax liability, as well as being taxed twice (once via corporate tax and a second time to the investor). Stock buybacks return capital more efficiently because an investor can always manufacture a 3% dividend by selling 3% of her stock while retaining control of the timing. Nonetheless, reliable dividends are valued. MLP distributions are generally not taxable when they’re paid and so their high payout model doesn’t suffer the same tax inefficiency. The MLP model of distributing its free cashflow relies on external financing (i.e. issuing debt and equity) to fund growth. The average corporation pays out a third of its profits and generally uses internally generated cash to fund growth. The MLP model of higher payouts and greater reliance on external funding sources is not inherently bad. Some feel it imposes extra financial discipline on management through making an explicit connection between capital and its intended use. Indeed, the Miller-Modigliani theory holds that investors should be indifferent to how a company sources its capital (debt, equity or reinvested profits); they should only care about how it’s invested. However, count Miller-Modigliani adherents among those MLP investors who were run over in 2015. The HNW investors who are the predominant financiers of MLPs like the high payout MLP model, so it has prevailed.

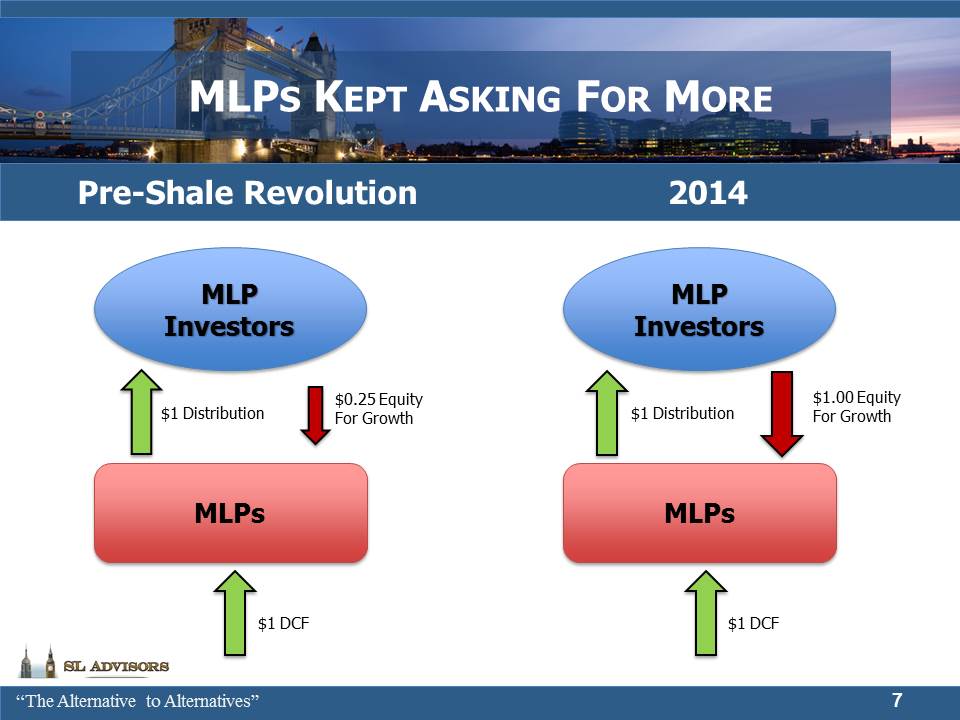

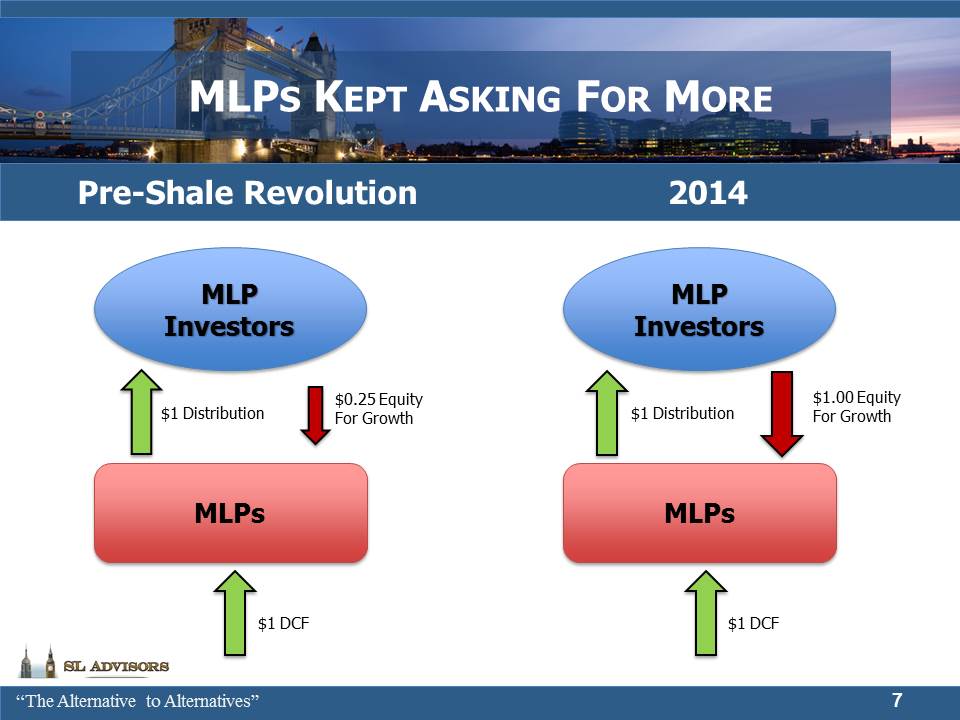

For many years, MLPs generated $1 of DCF, paid $1 of distributions (what MLPs call dividends) and tapped capital markets for $0.25-$0.50 to finance their growth plans. The shale revolution has challenged this model.

The Shale Revolution

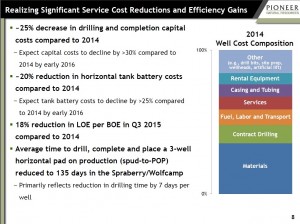

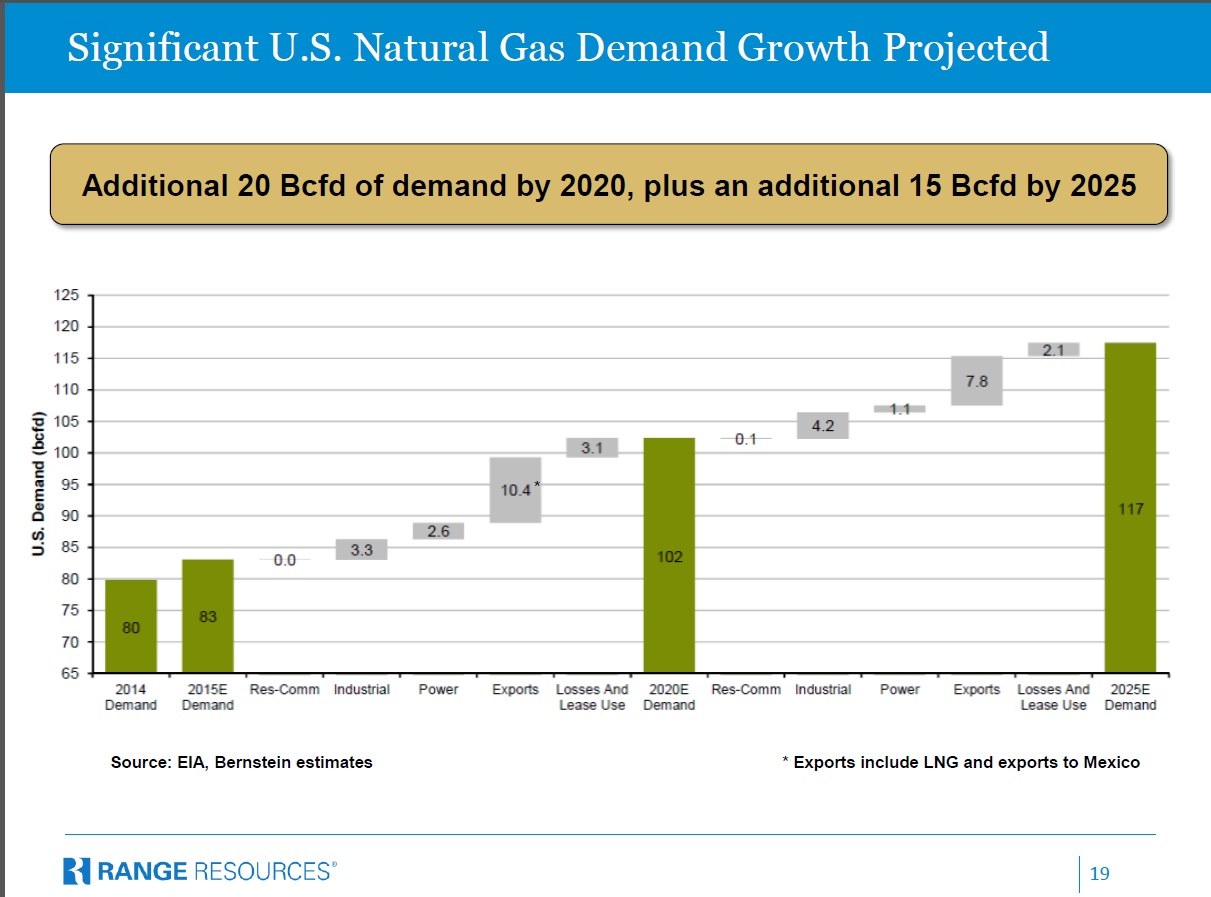

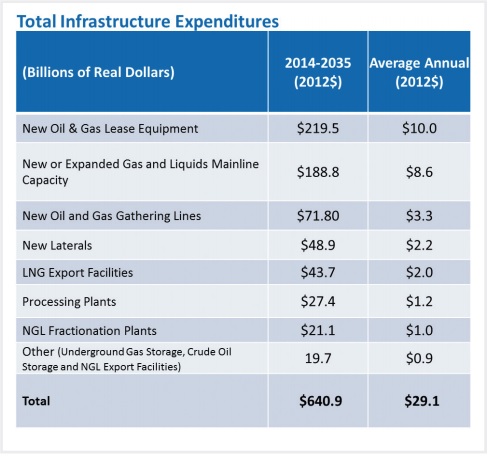

The development of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing unlocked enormous supplies of crude oil, NGLs and natural gas in parts of the U.S. that weren’t established sources of hydrocarbons. Increased output from regions not previously supported with infrastructure added an important growth element to the MLP story. In 2014 the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America estimated that $640BN of new investment in energy infrastructure will be required over the next twenty years, as this table shows.

The high payout MLP model whereby most cashflow is returned to investors via distributions meant much of the new capital to fund this growth would need to be externally financed.

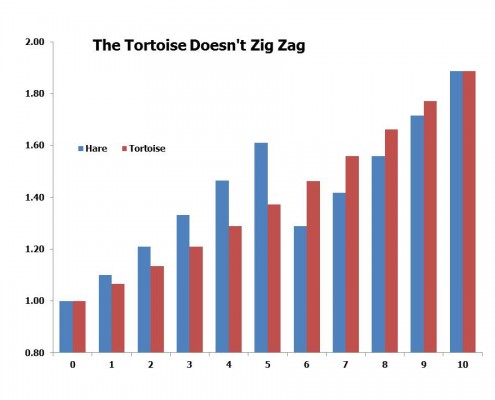

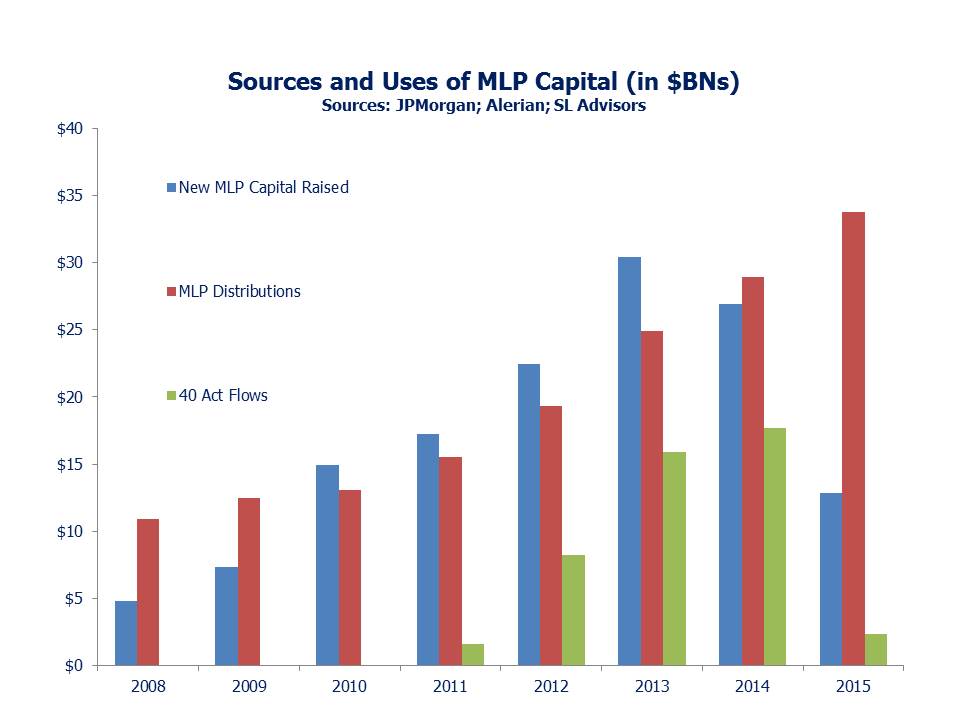

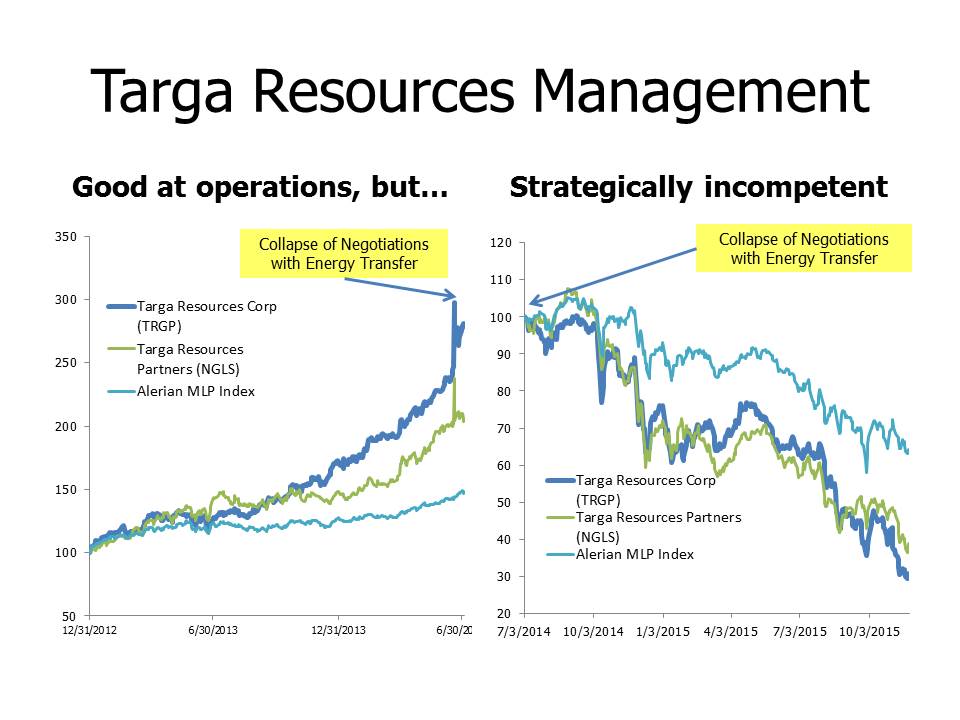

Tapping pools of investor capital beyond the K-1 tolerant, taxable U.S. HNW faces formidable barriers as noted above. The most important new source was from smaller retail investors whose insistence on receiving the simpler 1099 tax reporting form was accommodated via the growing number of 40 Act funds that held MLPs. Falling crude oil challenged the growth element of the MLP story since reduced domestic production diminishes the need for new infrastructure.In spite of the collapse in crude oil, the fee-driven midstream MLP operating model turned out to be fairly robust to commodity prices – not immune, but with limited exposure. 2016 EBITDA forecasts for diversified midstream energy infrastructure names have been revised down by mid-single digit percentages; farther from the wellhead means less commodity sensitivity. Kinder Morgan’s 2015 operating results are coming in 5-6% below budget (and still up 5% on the year). Investors are clearly anticipating far worse. As fund flows to the sector fell and finally turned negative, HNW investors were unwilling to provide additional capital even while MLP equity issuance fell. In 2015, MLP returns were dictated much more by capital flows than operating performance.

The high payout MLP model has come in for criticism from some who argue that MLP distributions are partially funded by issuing equity. This is untrue, but what is clear is that the growing infrastructure need to support increasing domestic hydrocarbon production has severely strained the available sources of capital. We believe 2015 performance is about the inadequacy of the long-established investor base to meet this growing need and the inability of alternative sources of capital to fill the gap. Operating results at midstream infrastructure businesses remained resilient with only modest exposure to collapsing crude oil prices. The growing conflict between high payouts and increasing growth plans is exemplified by Kinder Morgan.

Kinder Morgan

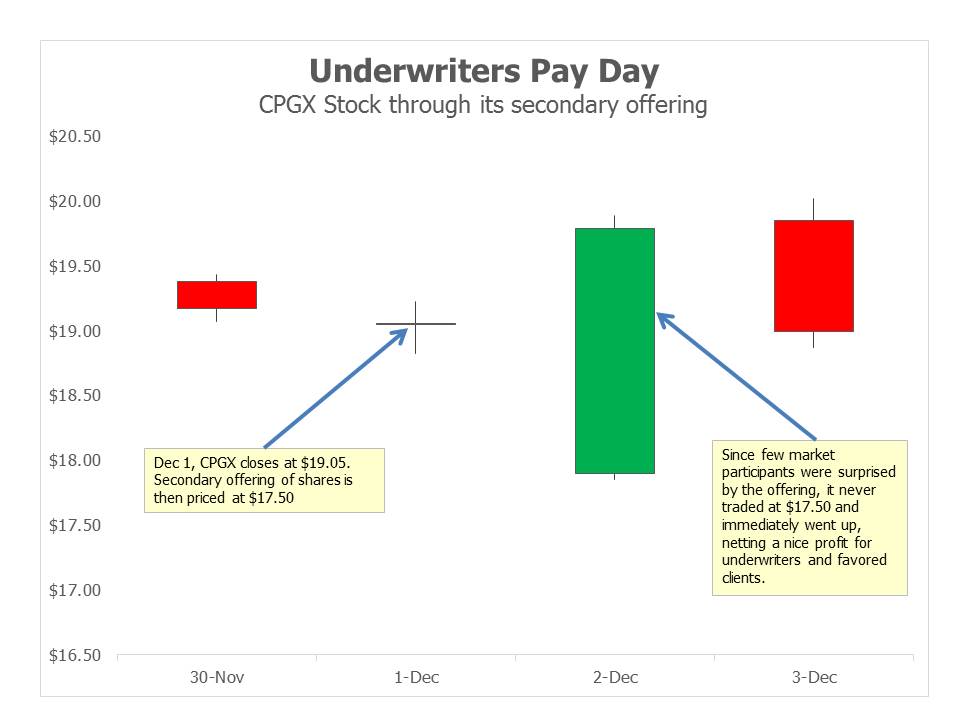

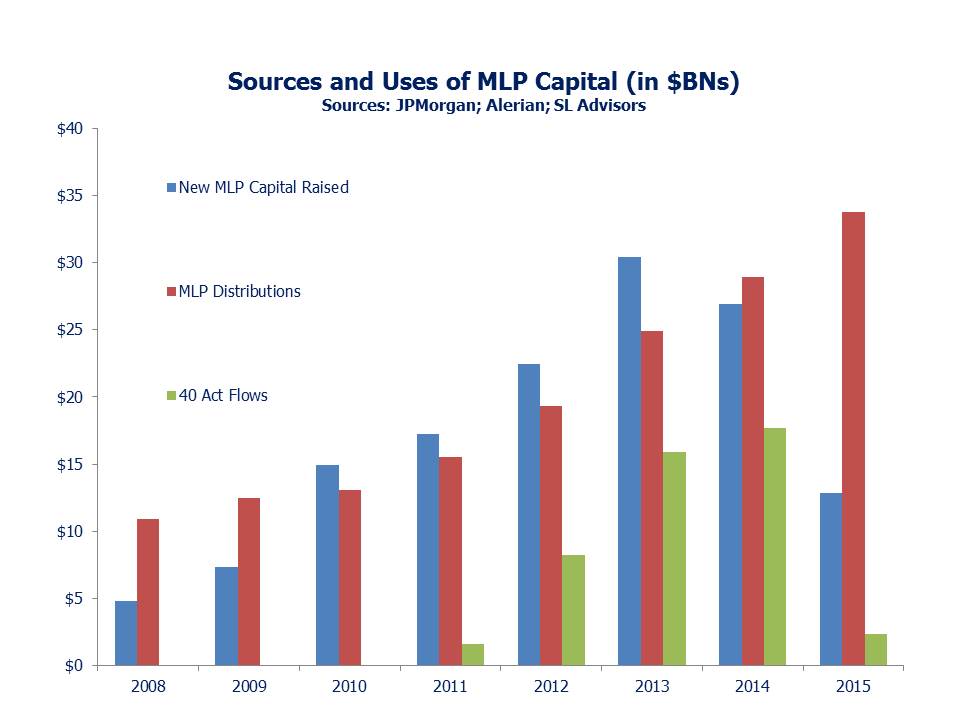

A simplistic model of how MLPs fund themselves is to examine what portion of the distributions MLPs pay out is then tapped as new capital via IPOs and secondary offerings. New equity raised increased from $5BN in 2008 to around $30BN in 2013. Distributions received by MLP investors grew from $10BN to $25BN. Therefore, new capital went from taking half of MLP distributions to well over 100%. Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP) reflected this trend, as their need for new equity capital rose from 73% of distributions paid out in 2008 to 101% in 2013. KMP investors in aggregate were reinvesting all of their distributions back into the business.

For a while the industry’s need for additional capital came from the growing number of MLP-focused ETFs and mutual funds, whose inflows increased tenfold from 2011 to 2013. This helped bridge the gap between the limited desire of K-1 tolerant MLP investors to reinvest more of their distributions back into the sector and the need of MLPs to finance growth.

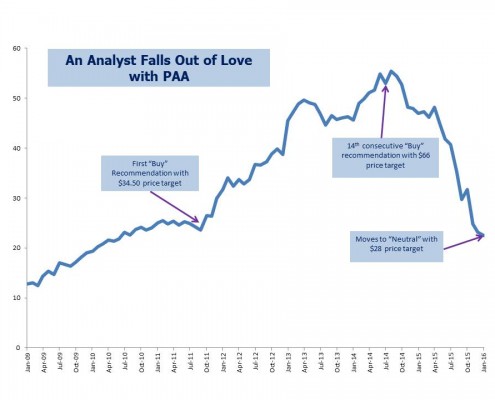

Nonetheless, the yield on KMP units remained stubbornly high, consuming much management attention as their ambitious growth plans pushed up against the limits of customary MLP investors to provide financing. In 2014 they embarked on a significant restructuring that eventually resulted in a catastrophic destruction of value and betrayal of their core investor base. Recognizing the limits to external financing as an MLP, they became a conventional corporation (a “C-corp”) instead. Although this now gave them access to virtually any public equity investor, they persisted with the 100% MLP payout model and its reliance on external financing for growth. This variance with the more typical corporate funding model of a one third payout ratio and mostly internal financing eventually drove their cost of equity to where it no longer made sense to raise external funds. KMI had many choices including cutting their growth plans, selling assets and seeking JV partners. However, the 2014 restructuring had been about financing their growth and in 2015 that remained their priority.

For a while the market supported the new structure. KMI shares maintained their uptrend into 2Q15, but as the inflows to ’40 Act funds petered out and switched to outflows in the Summer the increasing selling pressure on MLPs affected KMI too. It was in some ways similar to a bank run; as long as the market believed they could finance growth by issuing equity at a 5% yield, they could. As the market began to question that by pushing the yield higher, their growth prospects became less attractive in a negative spiral.

Original KMP investors suffered enormously; they endured a dividend cut in 2014 as they received lower-yielding shares in Kinder Morgan Inc. (KMI); their exchange of KMP units for KMI was a taxable event; their new KMI units eventually collapsed, and then they suffered a second dividend cut in late 2015. KMI management owns around 18% of the shares, so they have suffered with their investors. It nonetheless shows that alignment of interests doesn’t guarantee good judgment.

KMI’s situation was different because they are bigger, more leveraged and have more ambitious growth plans than other MLPs. But the industry is being forced to reconcile its desired growth with the limited interest of traditional MLP investors to finance it. The shallow commitment of many ’40 Act fund investors became apparent when MLP prices stopped rising. The biggest monthly inflow to such funds of just under $3BN occurred in September 2014, merely a month after the Alerian Index peaked. A group that looks past the 35% tax drag prevalent on most funds and expense ratios as high as 9.4% (see Mainstay Cushing MLP Premier Fund[2]) can’t be expected to have done much research on their holdings. Their proclivity to be momentum investors, providing growth capital on the way up, continued on the way down. The cycle will probably repeat.

Valuation

At the risk of stating the obvious after such a year, valuations are as compelling as they’ve ever been for MLPs. The Alerian Index ended the year yielding 8.5% based on most recent distributions. Our SMA portfolio of GPs yields 7.3% and grew at 13.4% in 2015 (including KMI’s dividend cut). We expect 10% distribution growth over the next two years, and distribution coverage is 1.08X (excluding KMI which now covers its reduced dividend 4.6X).

Operating performance for many midstream infrastructure businesses was barely different in 2015 than expected a year earlier. For example, we went back and found JPMorgan forecasts of 2015 Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) per unit/share as they were in August 2014, when the market was peaking. We compared these forecasts with where 2015 results are coming in for the names in our MLP Strategy that are covered (around two thirds). DCF figures are coming in 1-2% lower than expected in the Summer of 2014, while their equity prices have fallen 40-50%. MLPs fell a long way for good reasons, but 2015 operating results were clearly not the major cause and we find it implausible that investors are looking ahead to far worse results in 2016. This is what prompted us to examine more closely the investor base, and to consider capital flows and the apparent unavailability of crossover buyers to invest at depressed prices.

What Next?

The absence of readily available capital to replace the exiting ’40 Act funds has highlighted the limited investor base. Although some commentators claim to see increasing institutional investment in MLPs, it’s more limited than they suggest. Google “Pension plans and MLPs”, examine SEC filings or look up who are the largest owners of MLPs, and you’ll find little evidence of pension funds, endowments or foundations. Such institutional investors that do exist are managing money on behalf of retail and HNW investors who have chosen the sector. There simply aren’t large pools of professionally managed institutional capital able to opportunistically and quickly increase their exposure to MLPs. The tax barriers substantially reduce the portion of the return they can keep, which drives up their required return (although current valuations may well be sufficient to draw in such capital in the months ahead). The fact that most MLP ’40 Act funds are highly tax-inefficient demonstrates that better alternatives generally don’t exist, unless you focus on MLP C-corps as we do. MLP closed-end funds (CEFs), which at least have permanent capital, nonetheless behaved like open-ended funds because forced deleveraging turned them into sellers too as prices fell. For example, Kayne Anderson (KYN), a large CEF, was down 51%. Even other, generalist mutual funds which can theoretically hold up to 25% of their assets in publicly traded partnerships (which includes MLPs) are unlikely to shift much of their assets without doing careful research on a new sector, making them relatively slow-moving. As ’40 Act investors have been redeeming, their sales require a K-1 tolerant HNW investor to take the other side, often increasing his MLP exposure in a falling market. Anecdotal reports of macro hedge funds shorting the sector added further pressure.

As a result, the supply of MLP funding has turned out to be quite inelastic. Since crossover investors from other sectors are constrained by taxes, finding a balance between demand for capital and its supply relies mainly on traditional MLP investors shifting more of their portfolios to MLPs, something that has required an unexpectedly substantial drop in valuation. The transfer from one type of investor to another has been highly disruptive.

Financing growth is the challenge facing the energy infrastructure industry. They have an advantageous tax structure but the investor base isn’t growing as fast as their need for new capital. How MLPs perform in 2016 and beyond will depend on how management teams resolve the conflict between their key investor base’s finite desire to reinvest more of their distributions and the industry’s growth plans. Clearly, new money from HNW investors required substantially higher yields, probably reflecting the fear that other managements will abuse them like Kinder Morgan and reinvest their capital for them by slashing payouts. The good news is that IPOs and secondary offerings fell sharply in 2015, reducing the portion of MLP distributions reinvested to below a third, lower than in 2008. This represents new buying capacity for the sector.

Kinder Morgan spectacularly demonstrated that converting to a corporation is not a solution. Smart management will slow existing growth plans so as to limit their need to access very expensive equity while maintaining payouts and will shift towards more internal financing, JV partners and asset sales. Buckeye Partners (BPL) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both fund all their growth internally and have ample distribution coverage. All the General Partners we own have have coverage >1X. Moreover, new projects should have higher required returns since MLPs’ cost of capital has risen. Less reliance on new equity should lead to faster per unit distribution growth in the future.

The MLP General Partner, as we have often written, still looks very much like a hedge fund manager and internally financed asset growth at the MLP can be just as profitable as using external capital. The pursuit of growth as a priority is not a value creating strategy, as Kinder Morgan showed. The shockingly high volatility of MLP prices in 2015 will lead to heightened perception of risk among investors for some time. The price collapse was not anticipated and initially we, like many others, struggled to reconcile it with steady operating results. In recent months our thinking has evolved to examining the investor base more carefully. We’ve concluded that capital flows were a far more important driver of MLP returns than operating results in 2015.

More modest growth plans can, by preserving payouts, attract more capital from long-established investors which will stabilize the sector and restore the trust between the industry and its providers of capital. Too much pursuit of growth will result in significant investor turnover and value destruction. Those MLP managements whose growth plans exceed investor appetite will abandon the MLP structure in favor of a C-corp, foregoing the tax advantages of the MLP structure in search of a bigger pool of clients and turning over their existing investor base in the process. More thoughtful management will tailor their growth to the MLP capital available. New equity issuance dropped sharply in 2015 coincident with fund outflows, and as a result the portion of distributions reinvested fell, potentially freeing up new capital to be invested. Current valuations are such that a demonstrated commitment to maintain payouts is all that’s needed to provide stability and thereafter positive returns. Our investment approach is guided by these views.

We are invested in BPL, KMI, and MMP

[1] Non ‘40 Act Exchange Traded Notes (ETNs) also provided MLP access to non-K-1 tolerant investors

[2] This was the expense ratio for the year ended 2/27/2015 as of 12/19/2015