Drilling Efficiencies, Crestwood and More Energy Transfer-Williams Shenanigans

Drilling Efficiencies

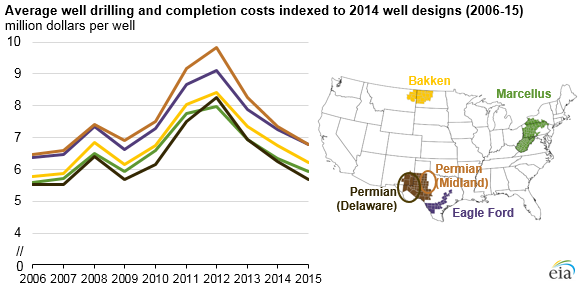

A week or so ago the Energy Information Agency (EIA) released the results of a survey showing the average cost to drill and complete a well in four of the major producing regions in the U.S. As the EIA chart shows, costs were rising going into 2012, but thereafter started to fall and maintained that trajectory as exploration and production companies aggressively sought improved efficiency from their technology and their service providers.

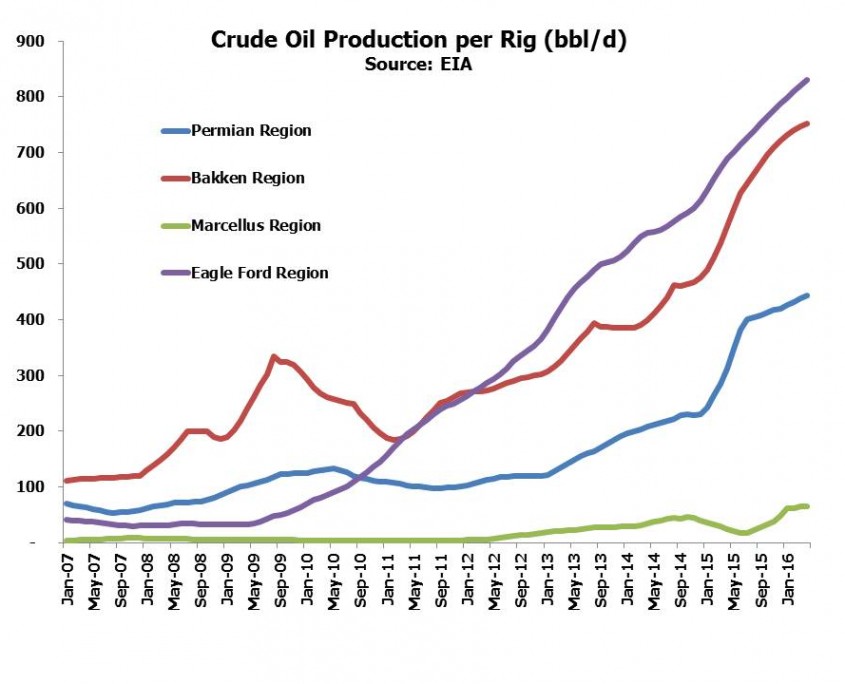

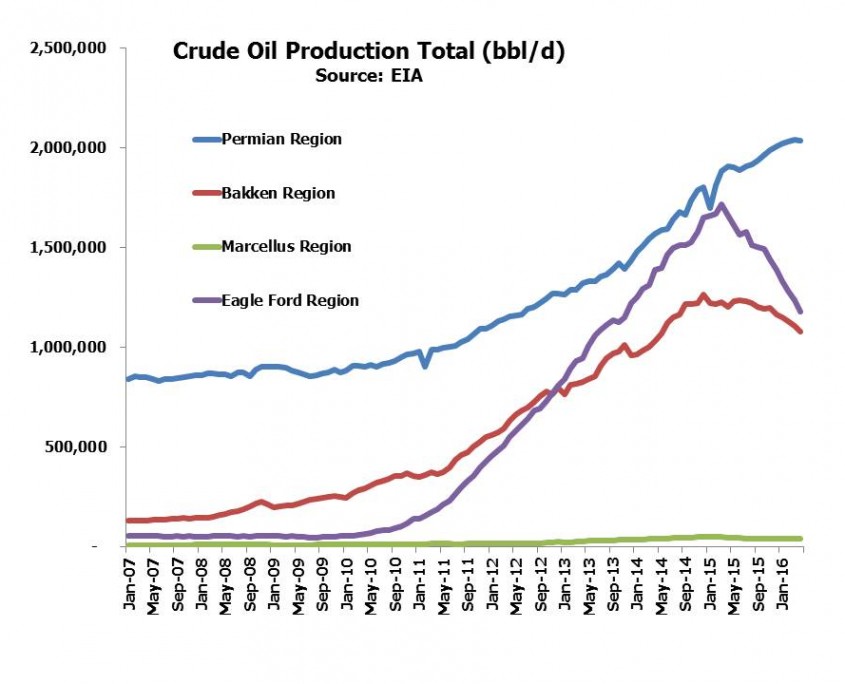

Although this drop in well costs has obviously been good news for the E&P industry (albeit less so for their service providers) it has been complemented by greater output per well. Using data from the EIA’s Drilling Production Report we have created the four subsequent charts, showing, respectively, output per rig for crude oil and natural gas, and total production of crude oil and natural gas, for each of the four regions highlighted by the EIA. Reduced costs to complete a well might accommodate lower average production per well, but in fact the reverse has generally been happening which has allowed IRRs (Internal Rates of Return) to remain substantially more attractive than would otherwise have been the case.

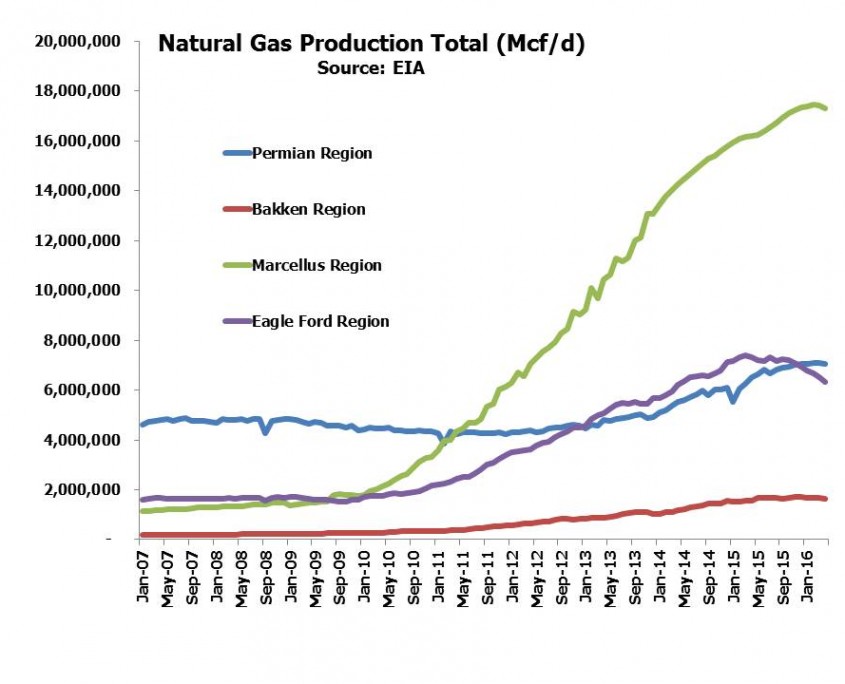

Natural gas production efficiency has improved dramatically in the Marcellus, which has caused the north east U.S. to switch from being a natural gas importer to an exporter and has begun to displace supplies from eastern Canada.

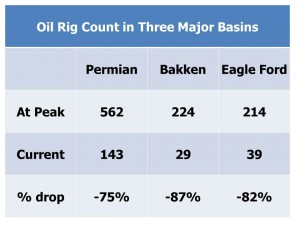

This is why crude oil and natural gas production have only fallen appreciably in the Eagle Ford, where higher initial production rates of new wells (due to higher pressure) are more than offset by faster decline rates than in other regions.

Natural gas output has soared in the Marcellus, aided by falling costs and a more than five-fold increase in output per rig since 2010. And meanwhile the rig count has come down sharply, as the table shows (Source:EIA).

This all represents a fantastic example of American technological innovation rapidly responding to the collapse in crude oil, probably faster than most observers had any reason to expect. Who would want to bet against continued American advances and improvements in this sphere?

Crestwood

A couple of months ago we wrote about Crestwood Equity Partners (CEQP), in The Math of a Distribution-Financed Buyback. Quicksilver is a bankrupt E&P company that had asked the bankruptcy court to reject Crestwood’s contract to provide gathering and processing services. There isn’t much case history of courts resolving contractual disputes between MLPs and their customers, but the travails of many domesric drillers has certainly drawn attention to this aspect of the MLP business model.

On Wednesday, Crestwood announced they had signed a ten year agreement to provide such services to BlueStone Natural Resources, the acquirer of Quicksilver’s Barnett Shale acreage. Previously shut-in wells will be re-opened and the contract, which consists of both fixed-fee and percent of proceeds terms, commits BlueStone to refrain from constraining production for economic reasons through the end of 2018.

It’s just one contract out of tens of thousands across the industry, but its constructive resolution highlights the symbiotic relationship between E&P companies and their infrastructure providers.

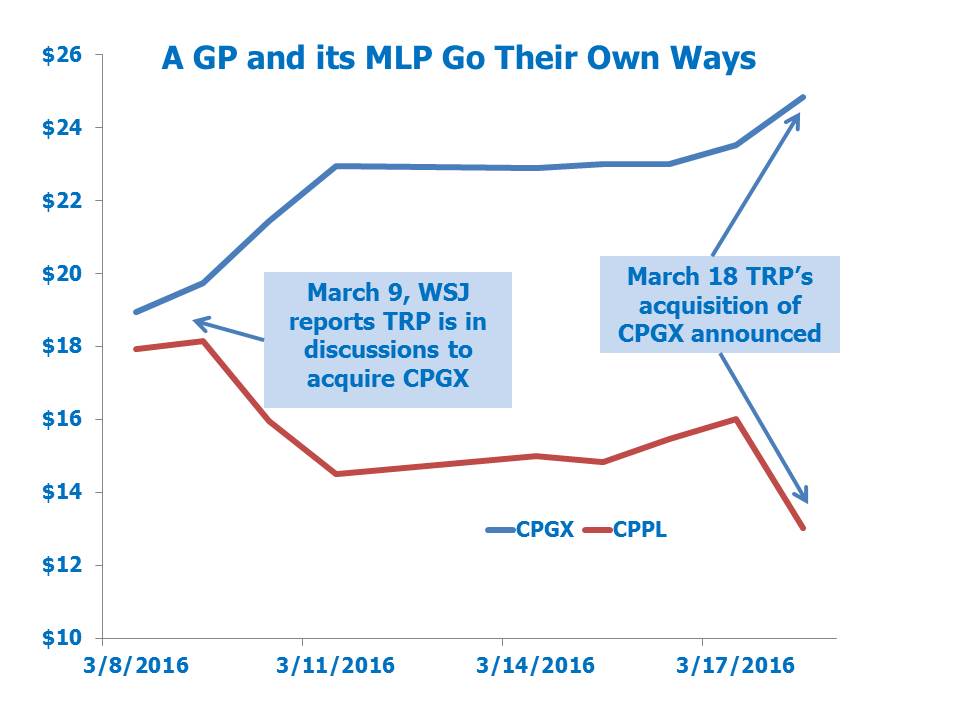

Energy Transfer and Williams

Last week we wrote about the Energy Transfer-Williams Poker Game and further twists in the plot took place since then as Williams (WMB) sued Energy Transfer (ETE) and CEO Kelcy Warren for violating the merger agreement when they issued convertible securities only to ETE management. There are no sympathetic characters here, but one can already hear the WMB lawyer explaining in court that WMB initially rejected ETE’s overtures, then finally agreed and is simply seeking to close the transaction on the agreed upon terms. Or, ETE pursued WMB in spite of being rejected, finally got the deal they wanted and have now changed their minds.

I guess Kelcy Warren has earned the right to blunder; while it’s impossible to forecast a resolution, it’s becoming a little hard to envisage a happy combination of these two companies under present circumstances. The uncertainty represents a substantial pall over both stock prices; a grudging break-up payment from ETE to WMB might well be the outcome that lets both managements focus on their operating businesses and brings this sorry, absorbing episode to a conclusion.

One solution that distribution loving MLP investors will find almost unbearable to even ponder is for ETE to scrap the preferred offering, close the deal per the original agreement and suspend the distribution. With $4BN a year in cash flow at the pro-forma parent the $6BN cash payout would be retired in a year and a half with investors looking at a combined company trading at 3x cash flow with conservative leverage.

We are long CEQP, ETE and WMB.

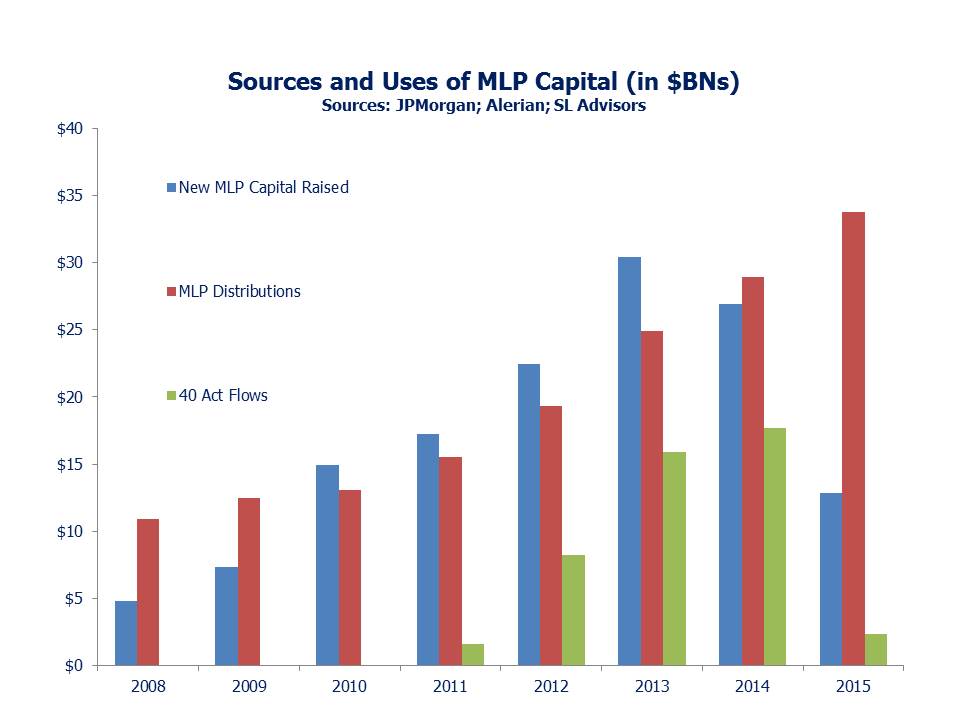

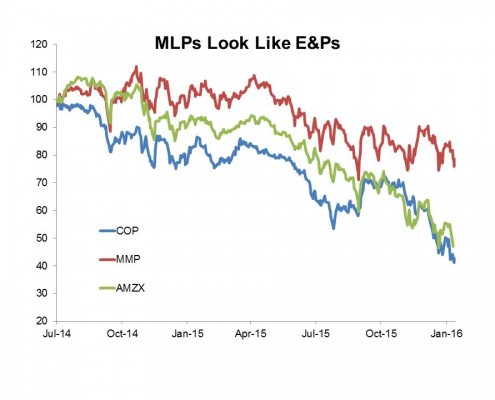

Whatever the true value of VRX, in the short term Ben Graham said the market’s a voting machine, and investing in public equities forces you to endure the popularity (or loss thereof) of your holdings. MLPs certainly found that even as their security prices offered ever greater discounts to value, the marginal investor was nonetheless more often a seller rather than a buyer.

Whatever the true value of VRX, in the short term Ben Graham said the market’s a voting machine, and investing in public equities forces you to endure the popularity (or loss thereof) of your holdings. MLPs certainly found that even as their security prices offered ever greater discounts to value, the marginal investor was nonetheless more often a seller rather than a buyer.

Around ten days ago Conoco Phillips (COP) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both released their 4Q15 earnings, and held conference calls on February 4th to discuss them. This coincidence of reporting is about all they have in common, but it caused us to look a bit more closely at an energy company (COP) that truly has commodity price exposure and what it’s doing about it.

Around ten days ago Conoco Phillips (COP) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both released their 4Q15 earnings, and held conference calls on February 4th to discuss them. This coincidence of reporting is about all they have in common, but it caused us to look a bit more closely at an energy company (COP) that truly has commodity price exposure and what it’s doing about it.