NuStar Acts Like a Hedge Fund

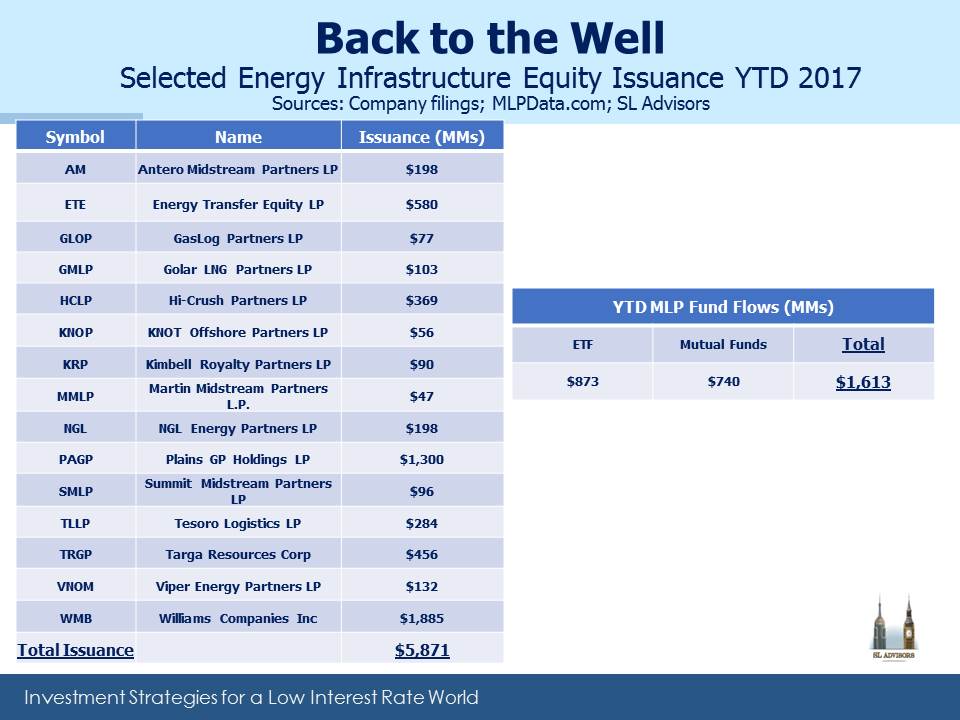

Last Tuesday, in a kind of return to normalcy, NuStar Energy (NS) funded an acquisition the way Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) normally do; by issuing equity.

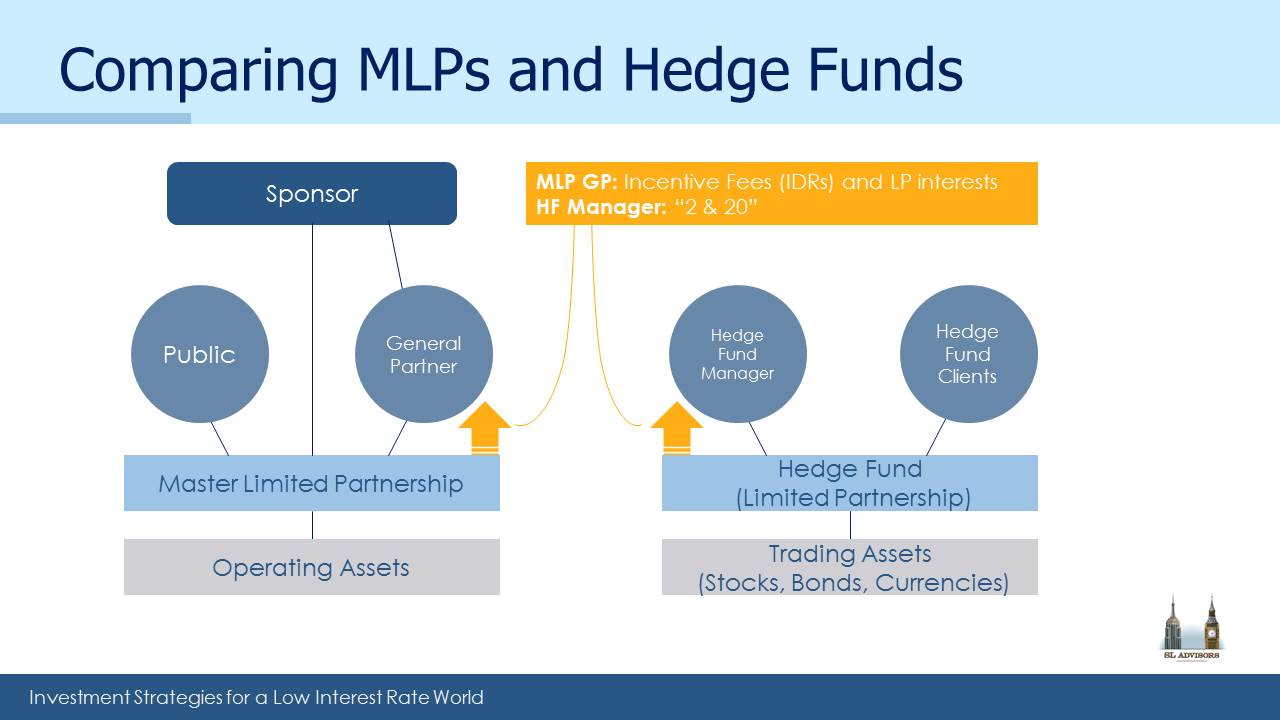

NS is an MLP controlled by a publicly traded General Partner (GP) called NuStar GP Holdings (NSH). As we’ve noted in the past, an MLP with a GP looks very like a hedge fund with a hedge fund manager. In this version of the analogy, NS is the hedge fund and NSH the hedge fund manager (i.e. hedge fund GP).

So to clarify what NS has done – they’ve invited in some new Limited Partners (think hedge fund investors) via their secondary offering of 12.5 million LP units raising $579MM (before fees). This money will, along with additional debt proceeds and cash, be invested in their $1.475MM purchase of Navigator Energy Services, owner of gathering and processing assets in the Permian Basin in West Texas. This looks just like a hedge fund leveraging new client capital to invest in assets, except that NS is buying physical assets rather than stocks, bonds or currencies like a hedge fund.

Like a hedge fund manager the GP, NSH, has directed all this activity while only providing their minor 2% GP share of the equity capital. NSH receives Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs) from NS which are a function of NS’s Distributable Cash Flow (DCF). Since NS owns more assets, they’ll throw off more DCF which can only be good for NSH. So like any competent hedge fund manager, NSH will receive a portion of the cashflows generated by assets that it controls but does not finance.

We’ve written about this in the past (see Energy Transfer’s Kelcy Warren Thinks Like a Hedge Fund Manager)

NSH CEO William E. Greehey understands this profitable asymmetry better than most, because he personally owns 21% of NSH. He also regularly buys additional NSH units on the open market. The Hedge Fund Mirage; The Illusion of Big Money and How It’s Too Good To Be True (Wiley 2012) revealed that 98% of the profits generated by hedge funds had gone in fees to managers. Being a hedge fund client is often financially punitive and rarely anything like as lucrative as being a hedge fund manager. Although MLPs have easily outperformed hedge funds, it’s often still the case that GPs do better.

Greehey’s $250MM personal investment in NSH is augmented with $150MM in NS, so he is in a way invested alongside other NS holders. However, since the IDRs paid by his NS units are returning to him via his NSH ownership, he’s enjoying substantially better terms than the others. It’s like investing in a hedge fund for no fees, which given that industry’s history is usually the only sensible way to do so.

Of course, there’s always the risk that NS might have agreed to pay too much to acquire Navigator Energy Services, in the same way a hedge fund might invest its clients’ capital in a low-returning asset. The risk of overpaying is largely borne by NS (i.e. the hedge fund clients) since it’ll reduce the returns they’d otherwise earn. The impact on NSH is more muted – after all, they didn’t provide the capital in the first place so their downside is a bit less cashflow received on virtually nothing invested. NSH has agreed to waive its IDR payments on the new money for the first ten quarters, which helps the numbers in the short term but will still nonetheless provide accretive cashflows for the GP indefinitely thereafter.

Since investors are generally advised to place their capital alongside management, which in this case is clearly in NSH, one might ask what is driving the selection of investors who instead choose NS? But we won’t ask the question too loudly, because it is the existence of willing NS investors that creates value in NSH. After all, what use is a hedge fund manager with no hedge fund? Similarly, an MLP GP without a ready market for units in the MLP he controls is worthless. So NS holders will gamely look past the 7% drop in stock price on the day the secondary was announced and draw solace from the exciting prospects described by management on their explanatory conference call (although failing to allow questions made the exercise fairly pointless).

Hedge fund clients often warmly regard new investors as confirming their earlier insight, and pay little heed to the possibilty of a dilutive return on the additional capital raised. The more astute GPs chant “We Love Our LPs”, which is the mantra of every GP in finance. As holders of NSH, we love NS investors. Not so much that we’d want to be them of course, but they can feel the love and that’s what counts.

We are invested in NSH