Adapting To America’s Low Rate Policy

President Trump continues to heap pressure on the FOMC to cut rates, to the alarm of every economist and bond analyst. Central bank independence is the gold standard for western nations, the only way to assure that politicians don’t seek to juice growth synchronized with the election cycle.

Fed chair William McChesney Martin Jr, who served in that position longer than anyone (1951-1970), was credited with describing the Fed as, “…independent within the government, not independent of the government.”

Central bank independence really means immunity from short term political pressure. Few argue that cental banks shouldn’t be politically accountable. The Fed’s twin mandate of maximum employment with stable prices is set by Congress and could be changed by Congress.

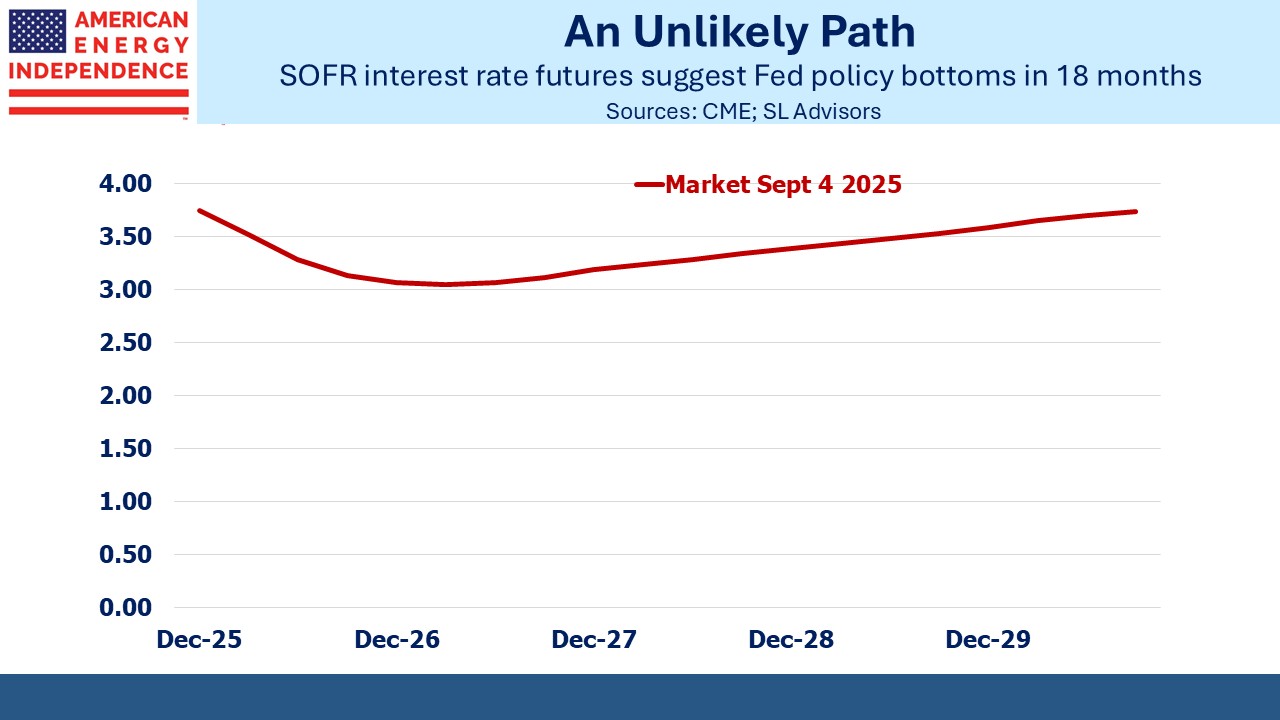

Trump isn’t the first president to call for lower rates, but as with most issues that get him exercised he is a relentless opponent willing to break norms to achieve his goals. The market is beginning to price in a Trump-managed rate cycle. It seems likely to me that his steady pressure on the Fed will tend to force short term rates lower for the rest of his term, as he finds more ways to change some FOMC members and intimidate the rest.

We are heading into a period of increased inflation tolerance. Whether or not actual inflation moves sustainably higher, few would confuse Trump with a hard-money man. If you’re excessively worried about preserving your purchasing power, arrange your investments appropriately into sectors that will respond well to rising prices – such as midstream energy infrastructure. Don’t rely on the president to help.

I increasingly run into people who differentiate between Trump’s policies and their implementation. Tariffs have turned out to be a national sales tax on imports. The Congressional Budget Office estimates they’ll generate $4TN over the next decade. Everyone who wrings their hands over our fiscal outlook and criticized the deficit increase in the One Big Beautiful Bill should welcome this new source of revenue to the Treasury.

Taxes aren’t inflationary. The prices of affected goods undergo a one-time increase. Tighter monetary policy in response would be exacerbating the headwind to consumption. Most states have a sales tax, and you’ve never heard that a monetary policy response was required.

Tariffs may not be that bad. But their implementation has been tactical and capricious.

The conventional wisdom supporting central bank independence is that it promotes low and stable inflation. There’s nothing magic about 2%. The FOMC disclosed their 2% inflation target in 2012 but for years previously had gravitated towards that level without formally adopting it. Many economists have argued that stable inflation is more important than the actual level, since it aids long term capital planning. Stability is more easily achieved around a lower number. Barry Knapp of Ironsides Economics argues that capex has historically been strongest during periods of low inflation volatility, such as from the 1960s-90s.

Our dire fiscal outlook is beginning to intrude. When the Fed raised interest rates in 2022 to combat the inflation caused by the Biden Administration’s fiscally profligate pandemic response, it drove up the cost of financing our Federal debt. With $37TN outstanding, we can no longer be oblivious to interest expense, which will exceed $1TN this year.

Trump has repeatedly accused Fed chair Jay Powell of costing us “hundreds of billions of dollars” by not cutting interest rates. As with much of Trump’s policymaking, his approach is combative and violates conventional norms. But it is reasonable to consider the Fed’s appropriate mandate given our fiscal outlook, the improvement of which both parties have concluded offers no political upside.

Federal debt has an average maturity of around six years and an average rate of 3.3%. If the Fed slashed short term rates to 1% immediately, it would take several years to meaningfully impact our interest expense. But eventually it would. If we targeted stable inflation of 3% and funded ourselves at 2%, a –1% real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) cost of financing would, over time, lower the real value of what we owe.

Mild currency debasement is a time-honored way for governments to repay less than they borrowed when adjusted for purchasing power, as I wrote in Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors.

The right way to do this is for Congress to debate the Fed’s dual mandate, to hold hearings and consider whether it should be changed. The world being what it is, the Administration is pursuing a different approach.

It’s easy to criticize the threat to the Fed’s independence. It’s also likely that for the balance of his term Trump will get his way. Because he’s willing to take some risk with inflation, investors should position accordingly. Unsurprisingly, we believe midstream energy infrastructure, with its inflation-linked business model, can be part of the solution.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: