Bond Investors Agree With the Fed…For Now

The Federal Reserve has brought transparency to their decisions. The famous “blue dots” which show visually each FOMC voting member’s forecast for rates provides insight into their thinking, even if it doesn’t attach names to each dot. We’ve come a long way from Alan Greenspan’s Senate testimony, “Since becoming a central banker, I have learned to mumble with great incoherence. If I seem unduly clear to you, you must have misunderstood what I said.”

Transparency has removed the mystique. It’s now clear that the Fed doesn’t know much more than the rest of us about the economy. They’re also only average forecasters. Ever since the blue dots laid out the likely path of short term rates, which the Fed largely controls, they’ve consistently overestimated where they would set rates. It’s been a source of some amusement – if they can’t even forecast their own actions with accuracy, how can they forecast the economy?

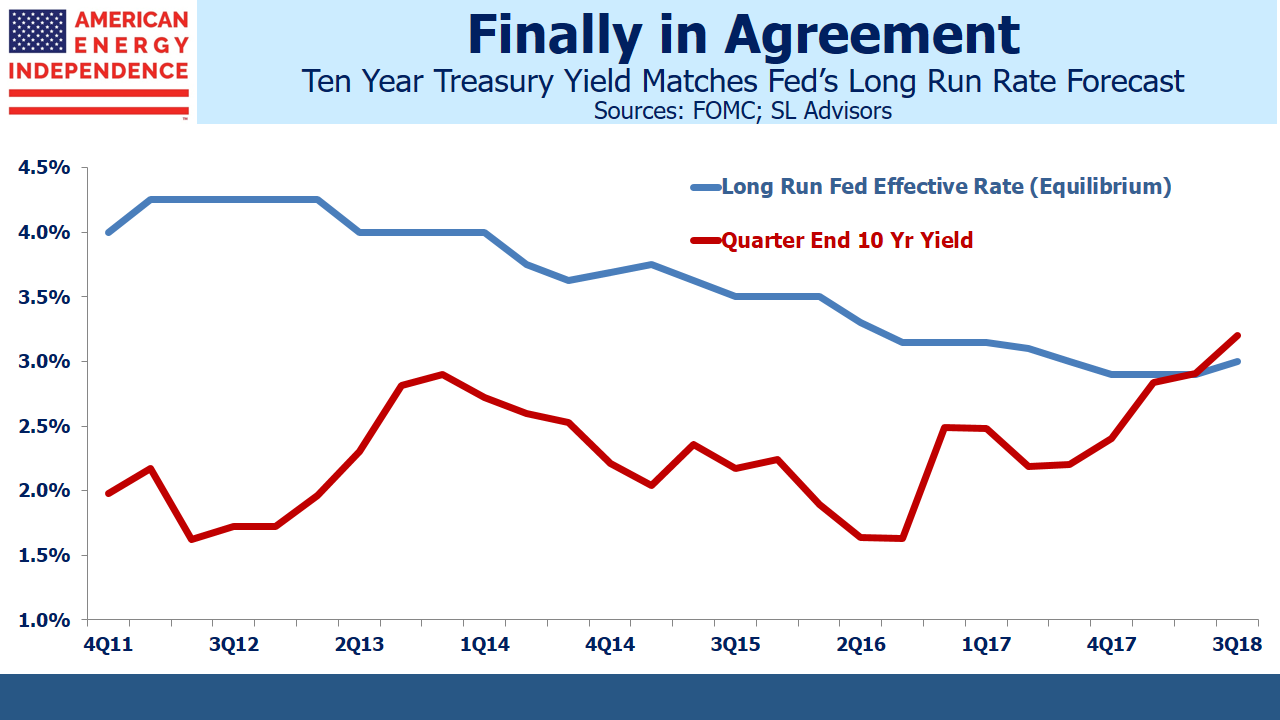

Bond investors long ago concluded that rates would stay lower for longer than the FOMC thought. Ten year treasury yields approximately reflect the bond market’s expectation for short term rates over the next decade. If the FOMC’s thinking aligns with investors, the Fed’s long run forecast of the Federal Funds rate should be similar to the ten year yield. This is the neutral rate, the equilibrium that they regard as being neither accommodative nor restrictive. Historically, it was believed to be around 2% above inflation, for a “real” rate of 2%. Since the inflation target is itself around 2%, 4% was held to be the equilibrium Fed funds rate.

As the Fed provided greater transparency, it revealed a yawning gap between their thinking and that of bond buyers. The bond market turned out to be right, and low treasury yields correctly reflected that short term rates would rise very slowly.

Interestingly though, the Fed’s equilibrium rate also began to slide lower. Since their inflation target of 2% hasn’t changed, it means their equilibrium real rate has dropped to only 1%.

One of the enduring puzzles of the past 25 years is why inflation has been so well behaved. Countless forecasters have been wrong-footed in expecting inflation to rise – with the U.S. unemployment rate at 3.7%, the lowest in living memory, few could be surprised if inflation does move sharply higher. But the FOMC implicitly expects that a less restrictive (i.e. lower real rate) will be needed than in the past to slow things down.

With the Great Recession now ten years old and the need for ultra-low rates gone, views are starting to converge. The Fed’s moderating long run forecast has now crossed the ten year treasury yield. For the first time since the regime of greater transparency, the market and the Fed are in agreement.

However, if treasury yields continue to rise, this will show that the bond market’s forecast of equilibrium rates is higher than the Fed’s. It’ll cause commentators to worry that the Fed is reacting too slowly to the threat of inflation.

It looks likely the Fed Funds rate will approach the 3% equilibrium by next year. The Fed expects moves beyond those levels to become restrictive, which is a normal part of the rate cycle. The interplay between bond yields and Fed Funds forecasts will become more important. So far, investors have been more accurate than voting FOMC members. If treasury yields head towards 3.5% it’ll suggest that the FOMC has allowed their equilibrium rate to drift too low. In that case, expect more White House tweets on rates.