The Changing Face of Oil Supply

There’s a developing paradigm shift under way in the oil market. It is manifesting itself through the quarterly earnings reports of many energy sector companies. At a high level, discoveries of new oil and gas fields recently fell to a 60-year low. Last year there were 174 oil and gas discoveries, compared with 400-500 a year until 2013. 8.2BN barrels equivalent of oil and gas were found, a fifth of the equivalent figure in 2010 and a level last seen in the 1950s.

Capex budgets for conventional exploration have been slashed. Chevron (CVX) cut their $3BN 2015 budget to $1BN last year. ConocoPhillips (COP) is pulling out of new deepwater projects altogether. Baker Hughes (BHI), who provide services to the industry, saw weakness in their non-U.S. business that was partially offset by strength in the U.S.

But not everyone is cutting back. Marathon Oil (MPC) is doubling its investment in new shale projects. Continental Resources (CLR) is spending $1.7BN which they expect will drive 20% annual growth in oil and gas output through 2020. Devon Energy (DVN) is planning to add rigs in the Barnett Shale where they’ll exploit advances in technology to “refrac” previously drilled wells. On DVN’s recent earnings call, CEO David Hager described their plans to use modern drilling and completion technology in areas that had previously exhausted their commercially viable output.

These companies and others like them are the customers of the energy infrastructure businesses that we own. For example, Enlink Midstream Partners (ENLK) is the direct beneficiary of DVN’s activity because their increased output will flow through ENLK’s infrastructure. It doesn’t hurt that ENLK’s General partner, Enlink Midstream LLC (ENLC), is owned by DVN. So we follow the plans of domestic Exploration and Production (E&P) companies even though we’re not directly invested in them.

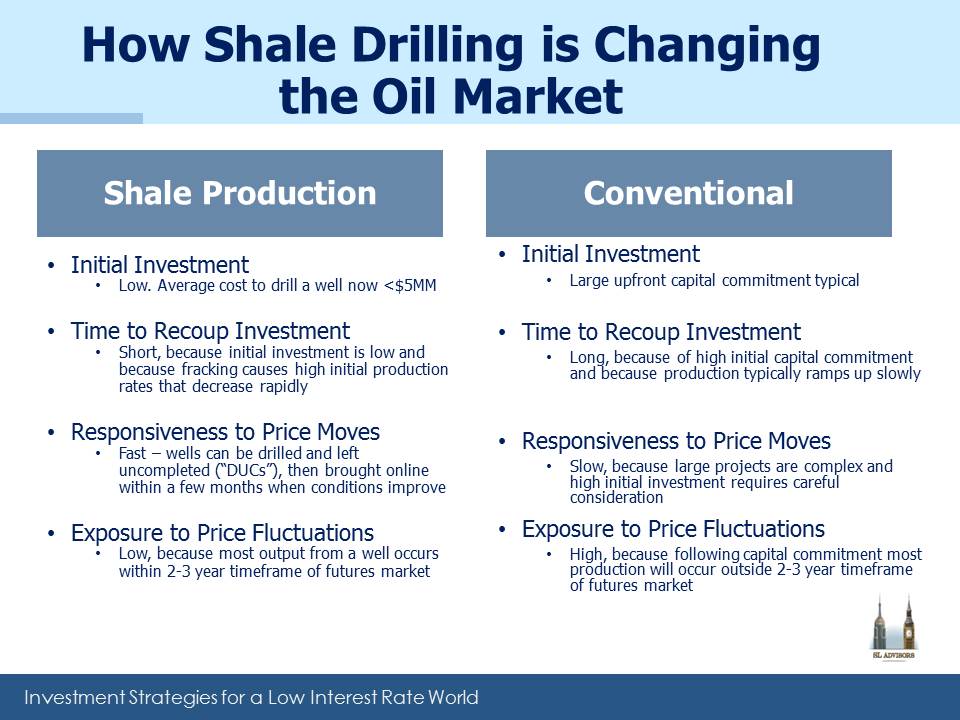

The crude oil market (and to a lesser extent natural gas), is shifting in ways that are incredibly favorable to the U.S. The key lies in the differences between shale and conventional production.

The reasons are in the table above, and were described in America Is Great! Conventional oil projects take a long time to implement and earn back their capital investment. Shale projects are the opposite. To understand how the U.S. is the big winner, consider how you would evaluate a conventional oil project costing, say, $1BN up front with a ten year payback period that is profitable only with oil above $50.

Once you commit, you can only hedge your crude exposure out for two or three years. You can analyze the oil market and arrive at reasonable price projections, but it was at $26 a barrel a year ago. So it might get there again. Shale technology keeps improving, so you have to assume that breakeven costs for shale output will continue to fall. It was shale output that caused the last crash. In approving the $1BN investment you have to make a judgment on the probability of a ruinously low oil price making your project unprofitable. And you can’t hedge this risk.

People often ask me what is the breakeven for U.S. shale production. There is no specific number, it varies from less than $20 per barrel in some places to well over $100. The production that is profitable takes place, and the unprofitable doesn’t. Profitability isn’t binary, with the industry all making profits above $X per barrel and losing money below. Costs can be substantially different even within the same play. It’s not a homogeneous industry. It’s more accurate to think of a finely graduated supply curve that increases output by 25-50K barrels a day for each $1 increase in price. Their short response time allows shale producers to drill and complete additional wells within months in response to improved economics.

Over the next ten years crude oil might stay above the $50 breakeven in the hypothetical project described above, and yet the project never get done because the risk of a price collapse was ever-present, hanging over the project’s IRR like the sword of Damocles. In this way, supply that could have been produced commercially will not come to market, allowing the nimble producer with a short response time to benefit from prices higher than they might have been otherwise. Because shale producers don’t face the same magnitude of price risk, they are in a far stronger position. Last week, the U.S. exported 1 MMB/D of crude oil. BP CEO Bob Dudley recently said that U.S. shale production will keep a check on any spikes in oil prices.

Price cycles in crude oil should be milder in the future, because the market has a shorter response time for new supply. Costs will continue to fall for “tight” oil and gas. America’s energy business has extraordinarily strong prospects.

We are invested in ENLC