Can An ETF Go Negative?

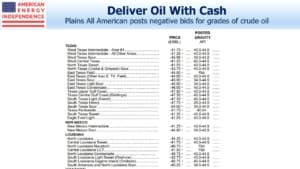

Monday was the day crude oil futures traded as low as negative $41 per barrel. As with the 1987 stock market crash, Monday’s participants will recall that date for the rest of their lives, the way I do October 19, 1987. Shortage of oil storage is the problem – nobody is going anywhere, so we’re not using much gasoline or jet fuel. Some have commented, only half-jokingly, that being paid $40 to take a barrel of oil would draw in a lot of buyers with the ability to temporarily repurpose other forms of storage.

But oil is a nasty product to handle. It is highly toxic, and leaks noxious gases such as hydrogen sulfide. If the air that you’re breathing contains as little as 0.1%, it kills you within seconds. This is why Texans aren’t filling up their swimming pools with the stuff.

The May futures contract traded 231 thousand times on Monday. One contract is equivalent to 1,000 barrels of oil. It traded from $17.85 to minus $40.32, a range of $58.17 which must be a record. A trader careless enough to be long 1,000 contracts who suffered a $10 adverse price move before dumping his position would lose $10 million. Given the volume and daily range, yesterday’s losses will be big enough to draw their own press coverage.

The United States Oil Fund, LP (USO) is an ETF that gives investors exposure to crude prices. Watching it has been the financial equivalent of a train wreck lately. Retail investors piled in last week, adding $1.6 billion of inflows. “Crude can’t stay this low” is sufficient analysis for many. Crude pricing is unlikely to correct before such adherents are wiped out.

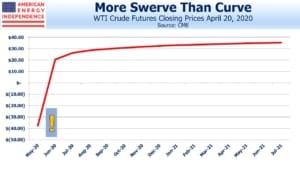

Many have concluded crude prices are wrong, but few have questioned USO’s raison d’etre. This is an ETF that buys futures contracts. Crude is in contango, meaning prices in the future are higher than today. Some interpret this as a forecast that the market must rebound, but forward prices are a poor predictor of what actual prices will be. What is clear is that the buyer of, say, July futures confronts the inevitable “rolldown” as today approaches July and actual supply/demand for crude increasingly determines the price. The rolldown is the price difference incurred as the holder of the July contract “rolls” into August by selling July and buying August at a higher price.

The bullish crude view has to constantly paddle upstream against the rolldown current. USO apparently rolled May futures into June last Friday, on terms that looked more like paddling up through spring rapids. Wiser and poorer for the experience, on Sunday they announced an improvement in their strategy. Henceforth, 20% of their futures positions will be invested in later-dated contracts, thus avoiding having to roll them all at once.

What is the point of an ETF that buys and holds futures contracts? Why don’t retail investors wishing to speculate on crude oil simply buy the futures themselves? Or an oil royalty trust? USO is a dumb way to bet on crude prices. A year ago, the July 2020 WTI futures contract was trading at $60 and yesterday was at $23, down 62%. Over that time USO has dropped from $13 to $3, down 77%. Its structure makes it hard to figure out how much it should move for a given change in crude prices. If crude can go negative, as the May futures did on Monday, can USO? Could USO go bankrupt?

Why do people bother with it? As well as being of dubious value to investors, few probably realize that they get stuck with a K-1 instead of a 1099, as USO is a partnership.

People buy USO because it’s easy to buy an ETF in a brokerage account, but more complicated to trade futures. Often it requires a separate agreement.

The reason is that the SEC regulates equities, including ETFs, while the CFTC regulates futures. USO and crude oil futures are both financial instruments – they ought to have a single regulator. The Senate Banking Committee oversees the SEC. The Senate Agriculture Committee oversees the CFTC, reflecting the original importance of agricultural futures. Brokers make valuable campaign contributions to the senators who oversee their regulator. The Finance/Real Estate/Insurance sector is the biggest source of such funding to the Senate Agriculture committee. No senator wants to give that up.

Merging the two regulatory agencies has often been suggested in the past, but is widely acknowledged to be a political non-starter. Even the passion for reform that followed the 2009 financial crisis was insufficient to overcome the economics.

USO is a result of our fractured regulatory structure, which is caused by the need for senators to raise money. USO buyers made a bad market call, but multiple overseers of financial instruments led to a poorer vehicle, which ultimately cost them even more. Yesterday USO was trading at a 27% premium to its NAV, indicating continued strong demand for this flawed ETF. It’s an instance of regulatory failure, caused by campaign contributions outweighing a more intelligent regulatory framework.